Doing some research, I came upon this colorful infographic that compares educational investment and results in a dozen different countries. No big surprises, but it’s easy to follow. It’s clear that Mexico spends a very small amount per student and achieves only modest results, and it makes sense to see France in the middle of per-capita spending and also in the middle of the results. Clearly, the US and the UK are out of whack–spending is high, but their results are middling. Why the mismatch? And why is the US’s purple circle so much larger than any other circle? Population accounts for only part of the reason why.

Avoiding Long-Term Commitment: The New Job Market

I was surprised to learn that most college presidents last about six years before moving on. A friend, who consults in the space, explained, “in many institutions, it’s just an impossible job.” Browsing through my LinkedIn connections, my first connection (his last name begins with “A”) is Len, a PR guy. Len has occupied nine different jobs since 1986; his longest stint was 6 years, and in today’s marketplace, that seems to be both (a) rare and (b) a long time. The February, 2012 issue of Fast Company ran an article entitled “The Four-Year Career” and declared “career planning” to be “an oxymoron.” The article points out that the average U.S. worker’s median level of job longevity is just 4.4 years.

The job market can be enormously frustrating, but deep down, most people understand that the economy is shifting–and that companies require employees for a period of years, not decades. In five years, Facebook has increased its her base from 10 million to 800 million; the first million Palm Pilots sold out in 18 months, and the first million iPhone 4s units sold in 24 hours; eBooks accounted for 1% of consumer trade books sold in 2008, and now, the number is over 20%. As the pace of change accelerates, the need for the same employees in the same seats evaporates. And, to counterbalance, as the pace of change quickens, the reasons why an employee would want to remain in the same seat for, say, five years, become less compelling for individuals in pursuit of active, productive careers.

But wait! There are at least two more pieces to the puzzle.

Cheryl Edmonds, featured in the Fast Company article about Four-Year Careers. To read the article, click on Cheryl’s picture.

The first is career switching. Not job swapping, but wholesale shifts in careers. Returning to the Fast Company article, Here’s Cheryl Edmonds, age 61, who shifts from engineering (1977) to a retail art business (1988) to corporate marketing at HP (1995), then heads to China to teach English (2009) before landing a fellowship with Metropolitan Family Services in Portland, OR (2011) in hopes of finding a new career in the nonprofit sector. Whether the person is 30 or 60, we’re seeing lots of these stories–people navigating the career marketplace as they might choose their next dog (whose longevity is likely to be longer than any current job), or vacation.

The second missing puzzle piece is formal education. Old thinking: go to college, train for a career, get a job, go up the ladder. Now, not so much, certainly not for a large population of liberal arts majors, and nowadays, even law school graduates are encountering a much-changed market for their trained brains. How to provide a proper college education for the likes of Cheryl, above? Marketing major? Engineering major? Liberal arts major? Get a degree, work for a few years, get another? I know a young woman whose college debt exceeded $100K, paid off half of it by taking a corporate job in supply chain management (thrilling!), hated it, sold real estate for a minute-and-a-half, then ended up in nursing school where she picked up a new $50K in debt to add to the unpaid $50K from her first degree. So here’s a system that’s not working very well at all.

On the positive side, all of this tumult leads to a far higher degree of personal control over one’s life than ever before. It also leads to a way of thinking that is counterintuitive for many Americans–if you are going to enjoy this degree of control, you need to think differently about your financial expectations, and about the management of your money. Multiple jobs in a single industry–you can expect to earn more money with every step up the ladder. Multiple careers–you will experience lateral steps, and you may earn less money in the next job, perhaps for a while, perhaps for a long time. (Freedom is not free.) For the entrepreneurs and business wizards among us, the constant jumps present fabulous opportunities to build wealth. For those who do not want their lives to be dominated by work, for whom a 40 hour week is more than enough, the less-fluid government and nonprofit sectors may be better places to work, but even employers are beginning to think twice about the ways they have operated for so long.

Brooke’s Illustrated Guide to Media Theory

On the Media host Brooke Gladstone, in cartoon form, illustrated by Josh Neufeld for The Influencing Machine, “a media manifesto.”

Brooke Gladstone is a brave woman. In the interest of explaining why media matters, she loses her head, plays the fool, embeds an Intel chip in her skull, becomes the robotic vitruvian woman, takes on the whole American political system (from its start in the 1700s), allows herself to be drawn in a hundred goofy ways by cartoonist Josh Neufeld, and…while on the high-wire, without a net…attempts to tell the truth about media and its influence on the ways that we think, believe, and act. In the early stages of this graphic non-novel’s development, it was “a media manifesto in comic book form.” Close enough. (If you’re interested, here’s how they did it.)

The Influencing Machine is now a paperback comic, the equivalent of a graphic novel, I guess, but it’s not easy reading. It’s a well-researched, deeply thoughtful examination of why media behaves as it does, how media interacts with law and government, and the interaction of history and philosophy. Pictures and the graphic novel style keep things light, and concise, but this is not a book to be read once, and it’s not a book to be read quickly. The starting point is news and public information, which may seem appropriate, but for most people, most media consumption is not news or information, it’s entertainment. And in that domain–which should include children’s programming, scripted comedy, scripted drama, and the variety shows that keep the masses satisfied (and have for centuries)–media’s influence is powerful, but rarely mentioned here.

She begins with a Victorian era story about machines that control people’s minds–or the fears that such a thing might someday exist.

Then, she explores the ideal of a perfect balance between effective governance and free flow of truthful information…only to find that such a balance is always outweighed by the government’s need for control.

Quoting German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860):

Journalists are like dogs–whenever anything moves, they begin to bark.”

Most profound–and most evident in today’s journalism–is “The Great Refusal.” Simply stated, by Gladstone, “Few reporters proclaim their own convictions. Fewer still act on them to serve what they believe to be the greater good.” With pressure from government to suppress potentially important information (for example, think: embedded journalists and the trade-offs they must make), and lacking the necessary resources to provide information based upon research and time to consider the story so that it can be presented in context, most journalists simply parrot press releases or official statements. Along the way, they must steer clear of various biases, and play within what most people perceived as reasonable boundaries. This behavior gets everybody into trouble because the whole point of journalism should be uncovering stories that ask the difficult questions…but the system is not set up to encourage, fund, or accept that kind of journalism. Instead, posits Gladstone, we live within a comfortable doughnut. What’s more, any journalist who strays finds himself or herself either (a) famous, at least for a while, or (b) difficult to employ. The risk of the latter is very real, and so, the status quo rules.

And so it goes, as Gladstone attempts (and is drawn to be) a bird of a feather, flocking together in homophily while watching global warming destroy habitat–she calls the phenomenon of groupthink “incestuous amplification” and illustrates it with references to global warming and weapons of mass destruction. She considers reasons to be okay and reasons to panic. She wonders about dumbing down and frets about the half of Americans who never read literature. She briefly touches on intellectual property laws, and G.K. Chesterton’s statement about journalism:

Journalism largely consists of saying ‘Lord Jones is dead’ to people who never knew Lord Jones was alive.”

And she wraps up with notions of globalism, and the ways that news is now a 24/7 global enterprise whose stories may affect us all.

There are few answers here, and the questions, well, they’re often difficult to shape and impossible to answer. At least she’s asking the questions, and placing herself in the middle of a digital storm. Thank you, Brooke, for steering clear of the obvious text presentation (mea culpa here, I’ll admit, as I write another few hundred words of text). The visual presentation, and the illustrations by Josh Neufeld, bring important ideas to life. And if there’s any interest in continuing the adventure to explore the many unexamined territories in the media landscape, count me among your first readers.

We need to talk about all of this stuff because the forces that demand silence are both powerful and ubiquitous. Even if it’s complex, even though it’s difficult to form into digestible bites, even if most people wonder why we’re obsessed with the way that media works, ought to work, and, sometimes, doesn’t work at all.

Below, some sample pages:

21st Century Debate

Although the series has been on the air for over five years, I discovered Intelligence ² within the past twelve months. Last night, I watched Malcolm Gladwell argue that college football was a bad idea because it involved the bashing of heads, and that, surely, there was some other game these people could play that would not, you know, involve bashing the heads of students (or anybody else, for that matter). On his team: Buzz Bissinger (he created Friday Night Lights, a popular TV series about football). Bissinger (see in the screen shot below) was strident, fierce and passionate in his well-researched beliefs: (a) colleges and universities should not be in the business of entertaining the masses, and (b) they should not be in the business of providing a farm system for professional football. On the other side, predictably, were two articulate football players who have moved on to bright careers (presumably, they, too have been beaten on the head several thousand times, but seemed to be okay with the way things turned out). Both were associated with FOX Sports: Tim Green and Jason Whitlock. In the advanced game of debate, their arguments proved to be less convincing.

Although the series has been on the air for over five years, I discovered Intelligence ² within the past twelve months. Last night, I watched Malcolm Gladwell argue that college football was a bad idea because it involved the bashing of heads, and that, surely, there was some other game these people could play that would not, you know, involve bashing the heads of students (or anybody else, for that matter). On his team: Buzz Bissinger (he created Friday Night Lights, a popular TV series about football). Bissinger (see in the screen shot below) was strident, fierce and passionate in his well-researched beliefs: (a) colleges and universities should not be in the business of entertaining the masses, and (b) they should not be in the business of providing a farm system for professional football. On the other side, predictably, were two articulate football players who have moved on to bright careers (presumably, they, too have been beaten on the head several thousand times, but seemed to be okay with the way things turned out). Both were associated with FOX Sports: Tim Green and Jason Whitlock. In the advanced game of debate, their arguments proved to be less convincing.

Football is not high of my list of things I care about, but the debate was compelling (and, having now watched several episodes, it’s fair to say that some are very passionate and others are not as much fun to watch). The series is called Intelligence Squared. There are two teams and three rounds. First round: each team member presents his case, his ideas in detail. Second round, they mix it up by arguing with one another. Third round: closing arguments. What’s the point? At the start of each show, the audience at NYU’s Skirball Center votes on a straightforward question: “Should college football be banned?” (yes, the question is black-white and there are grey areas, discussed during debate, but not a part of the ultimate vote on the simple question). Panelists answer questions from members of the audience. End of show: now that they have been presented with convincing arguments, the audience votes again. One team wins (Gladwell-Bissinger), the audience applauds, and we’re done for the evening.

The influence of Stanford Professor James Fishkin is evident here. Deliberative Polling also involves a baseline vote, then immersion in fact-based information seasoned by strong opinion, with a re-vote after the information has been received and processed.

A look at the website suggests that this is modern media done properly. Of course, you can watch or listen to the whole debate (or an edited version, audio+video or audio only). You can listen on about 220 NPR radio stations, or watch on some public TV stations. Or, you can watch on fora.tv. For each episode, the site features a comprehensive biography on each of the four debaters, a complete transcript, and a rundown on the key points made by each debater, along with extensive links to relevant research. In short, you can watch an episode, then read a lot more from the debaters and from the thought leaders who influenced the debaters’ opinions. It’s presented in a clean, easily accessible (non-academic) way. You can easily dive right in, learn a lot in a short time (if you wish), or spend a few hours to deeply consider what was said, why it was said, and why the voting audience did or did not change its collective mind.

A look at the website suggests that this is modern media done properly. Of course, you can watch or listen to the whole debate (or an edited version, audio+video or audio only). You can listen on about 220 NPR radio stations, or watch on some public TV stations. Or, you can watch on fora.tv. For each episode, the site features a comprehensive biography on each of the four debaters, a complete transcript, and a rundown on the key points made by each debater, along with extensive links to relevant research. In short, you can watch an episode, then read a lot more from the debaters and from the thought leaders who influenced the debaters’ opinions. It’s presented in a clean, easily accessible (non-academic) way. You can easily dive right in, learn a lot in a short time (if you wish), or spend a few hours to deeply consider what was said, why it was said, and why the voting audience did or did not change its collective mind.

The topics are provocative (and always simplified so they can be stated as a yes/no question for voting). Some examples:

Success! Good Health! Longevity! Fabulous Children!

You can do it! You’ll need a college degree and you’ll need to move to a place where 21st century America’s promise shines. Seattle, the SF Bay Area, New York City,

Boston, and the ring around Washington, DC.–those are the places where innovation is held in high esteem and is most likely to be funded so that new companies can be born, grow, and change the economic picture for employees, shareholders, and those smart enough to live nearby.

These are the places where venture capitalists fund big opportunities, and if a company seems promising, a VC will often require a move to, say, Silicon Valley, or not to fund the company at all. The “thickness” of the job opportunities in the Silicon Valley (and a very small number of other places), and the thickness of people with the necessary skills to suit those needs, not only attracts the best (and highest paid) people to these centers, where their high incomes tend to generate more jobs for the local economy (usually with salaries that are higher than even unskilled high school dropouts will find at home). If you’re an attorney, you’ll make as much as 30-40% more if you work in these areas than in an old rust belt city. The same is true for cab drivers and hair stylists.

Much has been made of Google’s employee perks; they won’t play in Hartford or Indianapolis, but neither of those places, nor most other American cities, see the kinds of financial results and spillover effects in the community enjoyed by the area around San Francisco. This is becoming the area that drives the American 21st century. And it’s very difficult for other cities to get into the game.

Author and UC Berkeley Professor Enrico Moretti has just published a book that presents a compelling picture of the much-changed US economy. The title of the book, The New Geography of Jobs, undersells the concept. Yes, if you can, you should move to any of these places, where you will make more money than you will at home–regardless of whether you are a high school dropout or a Ph.D. You will probably live longer, remain healthier, provide a better path for your children, live in a nicer home, have smarter friends, smoke less, drive a nicer car, you name it… the American dream lives large in San Diego, but in Detroit or Flint, Michigan, it’s gone and it’s not likely to return any time soon.

Author and UC Berkeley Professor Enrico Moretti has just published a book that presents a compelling picture of the much-changed US economy. The title of the book, The New Geography of Jobs, undersells the concept. Yes, if you can, you should move to any of these places, where you will make more money than you will at home–regardless of whether you are a high school dropout or a Ph.D. You will probably live longer, remain healthier, provide a better path for your children, live in a nicer home, have smarter friends, smoke less, drive a nicer car, you name it… the American dream lives large in San Diego, but in Detroit or Flint, Michigan, it’s gone and it’s not likely to return any time soon.

Average male lifespan in Fairfax, VA is 81 years. In nearby Baltimore, it’s just 66.

That’s a fifteen year difference. This statistic tracks with education attained, poverty level, divorce rates, voter turnout (and its cousin, political clout), lots more.

Want to remain employed? Graduate from college.

Nationwide unemployment rates: about 6-10% for high school only, 10-14% for incomplete high school, 3-4% for college graduates.

College degrees matter…far more than you might think. In Boston, with 47% of its population holding college degrees, for example, the average college graduate earns $75k and the average high school graduate earns $62,000. By comparison, Vineland NJ–just outside Philadelphia in South Jersey, has just 13% college graduates, and a college graduate earns an average of $58,000, with high school graduates at $38,000. Yes, it costs less to live in Vineland, but over a lifetime, people who live in Vineland are leaving hundreds of thousands of dollars on the table, perhaps as much as a half million dollars over a lifetime.

Real cost of college, including sacrificed employment: $102,000. At age fifty, average college graduate earns $80,000, but average high school graduate earns $30,000.

If a 17-year old goes to college, he or she will earn more than a million dollars lifetime. If not, it’s less than a half million.

What’s more, 97% of college educated moms are married at delivery, compared with 72% of high school-only grads. Just 2% of college-educated moms smoked during pregnancy compared with 17% with a high school education and 34% of drop-out moms. Fewer premature babies, fewer babies with subsequent health issues. Almost half of college graduates move out of their birth states by age 30. By comparison: 27 percent of high school dropouts and 17 percent of high school dropouts. The market for college graduates is more national; the market for non-grads is more local.

Caught in the middle? The best thing you can do is hang out with people who are pushing their way up the productivity curve. That is, MOVE! Leave the town where things aren’t happening, and take a job, almost any job with growth potential, in a place with high potential.

While the arguments about fencing lower-income immigrants out persist, most people earning graduate degrees today are immigrants. And a high percentage of people who start significant new businesses, funded by venture capital, are first generation Americans.

Today, an immigrant is significantly more likely to have an advanced degree than a student born in the US.

Foreign born workers account for 15% of the US labor force, but half of US doctorate degrees are earned by immigrants. Immigrants are 30% more likely to start a business. Since 1990, they have accounted for 1in 4 venture backed companies. When they start a new business, they generate high-value jobs, which brings more money into the community (not any community, only the ones with a thick high-skill / high value workforce and a thick range of desirable jobs), and the people who fill these jobs generate more jobs in the retail and services sector, jobs that pay more in the high value areas than they do at home.

A century ago, investment money went to Detroit for its car industry, and to the midwest for productive factories. That era is ending. Innovation in the health sciences, technology, software, internet, mobile, and other fields is the driver of American productivity–but not everywhere. Clusters attract the best and the brightest from metros without the necessary thickness, leaving lesser places with fewer people who can make big things happen.

There is so much more here (sorry for the long blog post, but this is a very powerful book). We need to generate more college graduates, especially more men, and especially more people with STEM expertise (science, technology, engineering, math). We need to do a far better job in educating and creating opportunity (including opportunity for mobility) among those with fewer advantages. We’ve got a lot of work to do. First step: read the book!

A Book about Books

“I am an invisible man.”

“We were around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.”

“On a sticky August evening two weeks before her due date, Ashima Ganguli stands in the kitchen of a Central Square apartment, combining Rice Krispies and Planters peanuts and chopped red onion in a bowl.”

So begins three contemporary books: Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971), and Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake (2003). One is about African Americans, another is about the counter culture, and the third opens with a view of new Americans, attempting to recreate a dish she recalled from her native India. Our tastes change with the times–only sixty years separate Ellison from Obama.

With so many words propelled at us each day, so many stories on so many media, there’s not much opportunity to consider the big picture, to develop a sense of the stories we are telling one another. I suspect that’s what caused English Professor Kevin Hayes to write A Journey Through American Literature (Oxford University Press).

With so many words propelled at us each day, so many stories on so many media, there’s not much opportunity to consider the big picture, to develop a sense of the stories we are telling one another. I suspect that’s what caused English Professor Kevin Hayes to write A Journey Through American Literature (Oxford University Press).

In Hayes’s world, the word “literature” embraces poetry, travel writing, autobiography, and fiction. Whether Benjamin Franklin or Stephen Crane, Eugene O’Neill or T. Coraghessan Boyle, his examples consider the broad sweep of 250 years. His definition of literature includes bits of Seinfeld and The Simpsons, and acknowledges films as literature, too.

Skateboarding through media theory and aesthetics, Smithsonian American Art Museum is acknowledging videogames as art this summer. And I’m certain that every word in write in this blog, and every word you write in your email rants, will stand the test of time as great literature, too.

Yes, there is interesting, substantial work being done in all corners of art and media. Often, the work goes unnoticed, or receives a flash of publicity for fifteen seconds. It’s just too easy to forget about the good stuff until somebody says, or writes, “hey, this is worth a look!”

This summer, for me, Hayes is that somebody. Here’s a starter checklist:

- Walden by Henry David Thoreau

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

- The Iceman Cometh by Eugene O’Neill

- The Invisible Man by J.D. Salinger

- Travels with Charley by John Steinbeck

- Beneath the Underdog by Charles Mingus

- China Men by Maxine Hong Kingston

- The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

Yes, Hayes is an English professor. No, I will not write a term paper, nor will I abide by any deadline. This time, I’m not reading for the professor or the course or the grade. I’m reading for myself. And I plan to read these books not on a screen, but through the ancient technology of ink on paper. Some, I will buy in a used bookstore, some I will buy from the NEW bookstore that just opened not a mile from my home, some I will borrow, at no charge, from a good local public library.

Welcome to summer!

Learning from Woody

On July 12, 2012, Woody Guthrie would have been 100 years old. This poster commemorates a life well-lived, and a voice that has never rested. You can support the Woody Guthrie Foundation if you buy this poster. You can learn a lot from Woody. I did, as explained below.

“Hey kids, want to sing a song? Some of you might know this song, but the words can be hard to remember. Here’s a sheet with the lyrics…”

This land is your land, this land is my land

From California to the New York Island

From the Redwood Forest to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me.

Singing “This Land Is Your Land” as a group exercise begins an exploration of surprising dimensions. Note how broad, deep and wide Woody Guthrie’s river of highway manages to travel.

Just as most people’s knowledge of Martin Luther King begins and ends with an “I Have a Dream” speech and a murder in Memphis, most people’s knowledge of Woody Guthrie begins and ends with one popular song. Turns out, there was a lot more to Woody, and, a lot more to this particular song. Here’s a lyric that you might not have heard Woody sing:

There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me;

Sign was painted, it said private property.

But on the back side it didn’t say nothing;

That side was made for you and me.

Woody sang this song (and many of his songs) with different verses (see note 1 below). Among folk singers, and storytellers, this remains common practice (also, among jazz musicians, but rarely among the commercial performers whose recordings are usually the definitive versions of their songs). In fact, Woody’s own life story can be difficult to follow because he often recalled his own life as a storyteller might– with different details depending upon his audience.

As I think about Woody Guthrie, and about how people learn, I envision a different kind of education than most people find at school, an education based upon individual learning and ideas that connect with one another, and with the heart and soul. I think that’s a better way to learn, or, at least, i think that’s the way I learn.

Turns out, Woody’s full name was Woodrow Wilson Guthrie, and he was named for a presidential candidate, then president of Princeton University. By age 14, Woody was living pretty much on his own in his hometown, Okemah, Oklahoma; his mother had been institutionalized with the Huntington’s Disease that would later take her life, and his father was living in Texas (see note 2 below). Woody becomes a street musician, then leaves for promise of California, one more Okie whose life was shaped by the Dust Bowl tragedy. In Los Angeles, he sang hillbilly music on the radio as part of a duo, but spent lots of his spare time thinking about, and writing about, working class people who could not find work. Woody wrote protest songs, and, for a few months, wrote for a Communist newspaper (though he was never a member of the Party).

Learning about Woody in the 1930s leads the interested student (me, among them) into the plight of real people during the Depression; ways in which creative people somehow earn a living; why creative people sometimes find traditional work difficult to do; the importance of unions for the working man; the story of the Grand Coulee Dam and the Columbia River; socialism and communal living; the blacklists of the early 1950s; life in a singing group; writing an autobiography; the usefulness of cartooning (Woody drew cartoons); the work of the Library of Congress in preserving the nation’s heritage; the slow demise of Coney Island and Brooklyn in the 1940s; deportation of immigrants; the emergence of Bob Dylan and 1960s folk singers in Greenwich Village; the life of Leadbelly, an ex-convict (doing time for murder) who sang his way out of lifetime in prison to become a popular folksinger (he was Woody’s friend; “Goodnight Irene” was one of his songs); Sacco & Vanzetti and questions regarding fair trials; the concept of an artist’s legacy; a son carrying on his father’s work and then finding his own way as an artist and a man; a granddaughter finding her way through the music industry, too.

Clearly, Woody’s music and Woody’s story appeals to me. In writing these two pages, I’ve learned a lot, and I’m certain that I will follow up. That’s how I learn. I wonder whether most people learn this way. I suspect they do.

Notes:

1 – An interesting question for aspiring musicians: when is a song “finished?” Is a song a continuing work of art that should be malleable, or is it final at the time it is recorded. This conversation quickly leads to another about copyrights and how they work: which version of the song would be protected by copyright, and why?

2 – Later, Woody Guthrie would die from the same hereditary disease. This leads the student to a study of genetics, family trees and genealogy, and diseases of the nervous system. George Huntington’s 1872 discovery of the disease is an interesting story about how diseases are identified, and how medical research has evolved. Back further, one theory of the “witches” burned in 1672 in Salem, Massachusetts connects the women involved with symptoms associated with Huntington’s disease. Playwright Arthur Miller told this Salem story differently when he wrote his play, The Crucible, to get people to think more critically about anti-Communist campaign waged by the dubious Senator Joseph McCarthy.

3 – Further encouragement: I’m not the first to see the value of Woody Guthrie’s life and art as a platform for further learning in a many related areas of knowledge. Guthrie curriculum materials can be found here.

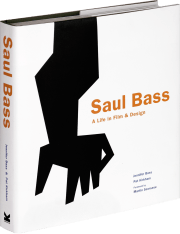

Anatomy of a Designer

“So I swallowed hard, gulped, and said ‘Roll camera… action!’ He (Hitchcock) sat back in the chair, encouraging me, benignly nodding his head periodically, and giving me the ‘roll’ signal as I set up each shot, matching them to the storyboard.”

“So I swallowed hard, gulped, and said ‘Roll camera… action!’ He (Hitchcock) sat back in the chair, encouraging me, benignly nodding his head periodically, and giving me the ‘roll’ signal as I set up each shot, matching them to the storyboard.”

The film was Psycho. The scene was storyboarded, and directed, by Saul Bass. Hitchcock trusted him. That was unusual. But then, Saul Bass was a pretty unusual guy.

The story, told in magnificent coffee table book splendor, begins in New York City, then quickly shifts to Los Angeles, where Saul begins to design movie advertisements, then movie posters, then movie campaigns. His modernist approach defined the era (seems like an overstatement, but it’s not). The films are iconic, but by today’s terms, old news: The Man With the Golden Arm and Exodus, for example, but Some Like It Hot and Around the World in 80 Days, and It’s a Mad, Mad World remain popular. And surely, you’ve seen Bass’s title work on the Hitchcock films, North by Northwest, Vertigo, and Psycho. Remember the cool animated opening sequence for the original Ocean’s 11? That’s Bass, too. Oh, one more: the entire opening sequence of West Side Story, where line art becomes aerial photography. And another; Walk on the Wild Side, whose mysterious cat eyes were later used for the famous Broadway musical. After the 1960s, his contributions to film begin to slow down (reasons below), but he still manages to design the opening sequences for Goodfellas and Cape Fear for Martin Scorsese, who writes the intro to this hefty book.

Anatomy of a Murder: one of the best Saul Bass movie posters.

Page after page, over nearly 400 pages, the astonishing Saul Bass: A Life in Film & Design by Jennifer Bass and Pat Kirkham, provides an education in visual communication. This is high level design, magnificently executed, and, in these pages, dissected with intelligent prose and step-by-step storyboards.

But wait, there’s more.

He found…that while film clients shared a common vocabulary and were familiar with thinking visually, for the most part, this was not the case with corporate clients. For the majority, this was their first experience working in the visual realm.”

Deep down, Bass was an extraordinarily gifted visual thinker… and quite the showman. His dash of show business played well among corporate executives, and, apparently, his presentation of new logos and corporate identities was quite memorable.

You know his work. It’s foolish for me to write much about it. The pictures tell the story better than words. So, as you think serious about buying this book–it should be a part of every creative professional’s library, enjoy the extra range of Saul Bass’s corporate work. Followed, briefly, by some of his equally extraordinary posters and related designs.

Logos designed by Saul Bass. From top left: Bell System, AT&T, General Foods, United Airlines, Avery International, Continental Airlines, Celanese, United Way, Rockwell International, Minolta, Girl Scouts of the USA, Lawry’s Foods, Quaker Oats, Kleenex, Frontier Airlines, Dixie, Warner Books and Warner Communications, Fuller Paints. (From Wikipedia)

This tribute site includes some of Bass’s posters, with an emphasis on his movie work.

And here’s the info about the book. Along with one last pitch from me: few creative professionals have enjoyed the breadth and depth of Mr. Bass’s extraordinary career. Just looking at the pictures will move you from interest to a true desire to do excellent creative work. Taking the time to read the text, and refer to it from time to time, makes a kind of magic possible. This is a book worth owning. And, if the spirit moves you, a gift that a friend or family measure will enjoy for years to come. Seriously.

Do You Think You Can App?

Think back to the time when you wondered whether you could desktop publish (before you knew what a “font” was), build your own website, or shoot or edit video? All of these were once unavailable to the average person. Now, Apple has filed a patent that could lead to make-your-own apps.

No surprise that message boards are filled with doubt. Making apps is too specialized, too complicated, too much of a commitment for the average person, too demanding in terms of knowledge and training and skills. Doubters point to iWeb, which was a make-your-own website tool that Apple provided, then pulled from the market.

Still, I wouldn’t dismiss the idea too quickly. No, most of us can’t or won’t build our own websites, but technology and invention race around the rocks–so we blog, and post images, and Tweet, and distribute information via tools that weren’t available the day before yesterday.

Do I want my own app? Sure, I guess, but the question suggests a solution chasing a problem.

If we flip the question, and assume, for example, that we (jointly) own an artisanal bread bakery, we might want to make it easy for our customers to know what’s baking, and what’s fresh out of the over, and we might not want to pay someone to build an app. A bake-your-own app might be just the thing for small business, or for authors who want to provide more than an eBook can easily provide, the list of potential problems that a homegrown app could solve is large. What’s more, the interactivity of a good app creates a high level of engagement between the provider and the customer, so apps could be the step beyond blogs and tweeting.

But I think there’s even more to the question. Blogs, tweets, apps–these assume current technology. And yet, we know that current technology lasts only a few years before the whole game changes. By 2015, we’ll be into advanced optical displays, a better cloud that makes the whole idea of local storage and local apps obsolete. Quite likely, we’ll be buying a broader range of devices–and I’m sure I don’t want a circa-2012 app as the my interface with thousands of internet radio stations (I really want easy-to-use internet radio in my car with lots and lots of stations from around the world).

Nothing is standing still–and that’s one of the challenges addressed in the Apple Insider article–how to build apps that easily (and automatically) customize for an increasingly varied range of devices.