For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain, Sam the Record Man. The stores are long gone. And that’s why I was so surprised to see an advertisement on the mobile phone provided by my hotel in Hong Kong–an advertisement that encouraged me to visit–who else?–Sam the Record Man in Hong Kong. My curiosity got the better of me, so I devoted an afternoon abroad to unravel the mystery.

For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain, Sam the Record Man. The stores are long gone. And that’s why I was so surprised to see an advertisement on the mobile phone provided by my hotel in Hong Kong–an advertisement that encouraged me to visit–who else?–Sam the Record Man in Hong Kong. My curiosity got the better of me, so I devoted an afternoon abroad to unravel the mystery.

I found Sam’s place in the Causeway Bay neighborhood, a few blocks from the very large and modern Times Square mall (which, of course, has nothing whatsoever to do with NYC’s Times Square). But this version of Sam’s was not a giant record store at all. It wasn’t even a storefront. It was located on the fifth floor of a nondescript old office building, and Sam is not Sam at all. His name is James Tang. And he is a very smart guy who cares a lot about recorded music. That’s why he opened what may be the world’s first record museum.

And no, I didn’t understand what that means, either. Briefly, here’s the theory. Just as the original version of, say, Leonardo DaVinci’s Mona Lisa, or Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night are available for public inspection at museums, so too should be the original versions of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, or Carlos Kleiber’s recordings of Beethoven’s Symphonies 5 and 7 with the Vienna Philharmonic (which many critics include on their top ten list of all time best). But these master tapes are not available to the general public–decades after they were created, they are locked away in the vaults of large corporations. Sam/James believes that’s the wrong thing to do. But that’s the just the beginning.

After some tea and conversation, he asked me if I’d like to listen to some music. I never say no to that type of offer. So we begin to listen to “Strawberry Fields Forever” and it sounds just wonderful. Better than any recording of the song I have ever heard, and not by a small margin. He explains that I am listening to a studio master tape. Voices are alive, instruments sound instinctively right, the mix holds each sound in its own distinctive space. In short, I feel as though I am in the studio with The Beatles.

He then asks me to listen to another rendition of the same recording. This time, I’m listening to a very clean vinyl copy, but it doesn’t sound nearly as good as the first recording. We go through various renditions, one on reel-to-reel tape, another on cassette tape, and more. We keep returning to the master tape, and there is no question that these renditions sound very different from one another. Then, we try some classical music, some jazz, and other pieces. The effect is more and less pronounced, but the pattern is clear, and I am absolutely certain that the differences are profound. But why?

He offers what I believe to be a very good explanation. First, he explains why the tape recordings sound better than the records or CDs. James shows me the first of several charts.

From the start, James explains that the ratings are completely subjective, but the more I listen, the more I respect both his ability to appreciate sound quality and his ability to place a reasonable numerical rating to describe the experience. Pegging the master at 100 percent, the reel-to-reel version sounded excellent, but the master sounded better. I experienced something similar when listening to the ultra-high-end systems, powered by the best professional reel-to-reel recorders with second generation master tapes (the original are in a private vault) at VPI, maker of superior turntables. And, despite my misgivings, I had to agree that cassette tapes really did sound a lot better than the CDs (he rates them at 50-55% vs. 30%; I cannot rate my experiences with this level of precision, but the difference was profound).

Where does vinyl fit into the matrix? Yeah, there’s a problem with vinyl. You see, vinyl is not struck from a master tape. Instead, the master tape goes through several steps before a consumer LP becomes available.

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

How about newer vinyl? You know, 180 gram special pressings worth $30 or $40 or more? To James’s thinking–and I keep hearing this from others I respect–you are better off buying a used version of the original record. Or, much better, tracking down a collectible first pressing from one of the labels that did lavish the necessary attention (say, Japan Toshiba’s Red Vinyl line from 1958-1974), and you may be very pleased with what you hear (on a very good two-channel stereo system).

James does sell the very highest quality collectibles in his shop, and for some people, that’s just plain heaven. For the rest of us, James initially sounds like he has taken an interesting theory a bit too far, but then, you listen. First you listen to the music, then you listen to James, then you listen to the music again and begin to realize that what he says makes a whole lot of sense. And then you realize that two or three hours of your time in Hong Kong isn’t nearly enough because he is so hospitable, so passionate, and so much the believer that you become one, too.

I have not stopped wondering whether, somehow, it would be possible to listen to the master tapes of the recordings I love. Sure, I’m happy with my growing collection of vinyl (typically used, typically in very good shape, typically $4 or so per disc, typically pressed in the UK or Germany under the good to very conditions), but James insists that there is more enjoyment on those master tapes, and I am fairly certain that he’s right.

The question, which is, for him, a quest, is how to gain the opportunity to listen to those master tapes. He is one man fighting the good fight, but he’s not doing to do it alone.

If you visit Hong Kong, do contact James Tang and ask for a tour of his museum and a demonstration of what I heard. I believe you, too, will become a believer.

There is lots and lots and lots more on his website.

We started with one of the past century’s best–Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1961-2 for Deutsche Grammophon. I had just picked up a $4 LP, in very good shape, from

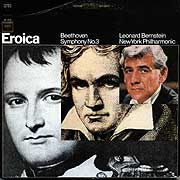

We started with one of the past century’s best–Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1961-2 for Deutsche Grammophon. I had just picked up a $4 LP, in very good shape, from  Next up: Leonard Bernstein from the same. Era. This was my LP, purchased decades ago, kept in it boxed set, played maybe ten times. This was a master work from Columbia Records at the label’s prime. The performance is ambitious, engaging, flowing–but the sound of the horns and the strings was compressed, very limited in highs and lows. We wanted to hear the depths of Beethoven explored by Bernstein in his prime–but the recording let us down.

Next up: Leonard Bernstein from the same. Era. This was my LP, purchased decades ago, kept in it boxed set, played maybe ten times. This was a master work from Columbia Records at the label’s prime. The performance is ambitious, engaging, flowing–but the sound of the horns and the strings was compressed, very limited in highs and lows. We wanted to hear the depths of Beethoven explored by Bernstein in his prime–but the recording let us down. Before going modern, we decided to go for Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, first on LP and then on CD, recorded in 1949–before stereo recording was available. This was state-of-the-art at the time, but the dynamic range was so limited on these recordings, they did not stand up to modern listening. Historical interest only.

Before going modern, we decided to go for Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, first on LP and then on CD, recorded in 1949–before stereo recording was available. This was state-of-the-art at the time, but the dynamic range was so limited on these recordings, they did not stand up to modern listening. Historical interest only. I had high hopes for my treasured 1995 CD set from Colin Davis and the Staastkapelle Dresden. Sure enough the CD really delivered–a full range of highs, lows and everything in-between. Wonderful placement of instruments. Lots of clarity, distinct individual violins and basses, just the right horn sounds. I was excited–but somehow, the listening experience was a few marks less than thrilling. After Karajan and Bernstein, the passion felt a little lacking. A fine performance is not the same as a thrilling performance, and when I’m listening to Beethoven’s Eroica, I want to be thrilled. But the sound was more satisfying here than it was on any of the LPs.

I had high hopes for my treasured 1995 CD set from Colin Davis and the Staastkapelle Dresden. Sure enough the CD really delivered–a full range of highs, lows and everything in-between. Wonderful placement of instruments. Lots of clarity, distinct individual violins and basses, just the right horn sounds. I was excited–but somehow, the listening experience was a few marks less than thrilling. After Karajan and Bernstein, the passion felt a little lacking. A fine performance is not the same as a thrilling performance, and when I’m listening to Beethoven’s Eroica, I want to be thrilled. But the sound was more satisfying here than it was on any of the LPs. Now here’s my last one. It’s a digital remaster from 1963, a CD box that I didn’t even know I owned. It’s the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig led by

Now here’s my last one. It’s a digital remaster from 1963, a CD box that I didn’t even know I owned. It’s the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig led by

AirStash. Simple idea: load some movies on a 8GB or 16GB SD card–the ones you use in a camera that are about the size of a postage stamp–then wirelessly connect the small AirStash device to watch movies (or review documents) on your iPad, iPhone, or Android device. It costs about $125. Use it once and you’ll carry it everywhere, as I do.

AirStash. Simple idea: load some movies on a 8GB or 16GB SD card–the ones you use in a camera that are about the size of a postage stamp–then wirelessly connect the small AirStash device to watch movies (or review documents) on your iPad, iPhone, or Android device. It costs about $125. Use it once and you’ll carry it everywhere, as I do. A ZOOM Q2H2. With cameras and camcorders now built into phones, why buy a small video recorder for $199? Because the sound and the picture quality is outstanding, but the device is small. What do I mean by “outstanding?” Video: 1920×1080, 30p HD. Audio: 24 bit, 96 kHz PCM. Record the results on an SD card.

A ZOOM Q2H2. With cameras and camcorders now built into phones, why buy a small video recorder for $199? Because the sound and the picture quality is outstanding, but the device is small. What do I mean by “outstanding?” Video: 1920×1080, 30p HD. Audio: 24 bit, 96 kHz PCM. Record the results on an SD card.

1980s: I’m buying lots of LPs.

1980s: I’m buying lots of LPs.