One of the less well-lit areas of human history is the history of children. Today, there are television channels, endless videos and photographs, schools of every description, as well as the occasional well-publicized story of a child who built a business or a charity. Our contemporary view of childhood is very different from the views held in the past, but I’ve always been insecure about the details.

Looking for a good book about childhood’s past, I waited for the new Second Edition of A History of Childhood, written by a Professor Emeritus from the University of Nottingham named Colin Heywood. Although written with scholarly correctness, it’s accessible, and it turns out to be a pretty good story, too.

He gets started in the Middle Ages, “a society which perceived long people to be small scale adults. There was no idea of education… and no sign of our contemporary obsessions with the physical, moral and sexual problems of childhood. The ‘discovery’ of childhood would have to await the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Only then would it be recognized that children needed special treatment, ‘a sort of quarantine’, before they could join the world of adults.” These early years are complicated because religious belief dominated; Puritans, for example, “did not necessarily have a high opinion of infants, the more zealous brethren assessing they were born as ‘filthy bundles of original sin’…

The Age of Innocence by painter Joshua Reynolds, circa 1788

By 1788, there are lovely paintings of innocent children, representative of romantic view, if not of all children, then certainly the fortunate upscale among them. She seems to be the perfect child, but parents remained conflicted about just what they were raising. There were constant ideological conflicts between innocence and depravity, superb and dreadful behavior, honorable and horrifying treatment, nature and nurture, independence and dependence.

To begin his fourth chapter, Professor Heywood begins with a provocative question, “To begin at the beginning, were children wanted?” Happily, the answer through the ages seems to be yes… but not too many! There were critics opposed to the whole idea, including the fourteenth century poet Eustache Dechamps, who write “Happy is he who has no children, for babies mean nothing but crying and stench; they give only trouble and anxiety.” In the throes of motherhood, Hester Thrale (1741-1821) wrote in her diary, “this is a horrible Business indeed: five little Girls, too. & breeding again, & Fool enough to be proud of it! Oh Idiot!’ What should I want more Children for?”

After leading us through history of delivery, naming, godparents, and other ceremonies, we’re faced with the unfortunates, the unwanted children and their unhappy parents, and deepening the despair, the common death of infants and young children, no less a tragedy then.

Still, children survive and thrive. There are more and more of them, especially after we determine that they are better educated than put to work as small versions of farm hands and factory workers. In fact, they thrive, leading first to the astonishing 3 billion people on earth by 1900 (just as public education is beginning to take shape), then (beyond the scope of the book), taking us to 8 billion by about 2025.

As we begin toward the modern age, fathers have more time at home, so childcare, and the love of children, shifts from primarily a mother’s role, to an increasingly common model of shared parenting.

Heywood provides much more than a historical overview. He takes us into the room with the child as he or she grows up. Example: learning to walk, children were discouraged from crawling. Why? Indoors, floors were often shared with animals, and there was a certain discomfort in seeing one’s offspring propelling himself or herself in the same manner as a pig. There was also the cold of those floors, and the filth. Better to walk up on two legs–but not too soon, lest the child become crippled or otherwise deformed, as so many others seemed to be.

There have always been toys, and games, and nursery rhymes, too. And questions about gender stereotypes. “In antebellum America, for example, many girls preferred outdoor activities such as skating and sledding to playing with dolls. Toward the end of the century…three quarter of boys studied [were] playing with dolls, while girls sometimes acted more aggressively than their parents might have hoped.”

For those with mobility, some money and parents who would take them, there was “an impressive array of entertainments designed to instruct as well as amuse in eighteenth century England in the form of ‘exhibitions of curiosities; museums; zoos; puppet shows; circuses; automata; horseless carriages; even human and animal monstrosities.” Working class families made do with “cheap and cheerful entertainments such as dancing on the streets to a barrel organ or enjoying the hustle and bustle of a street market.”

There is evidence of children’s books in England as early as the 1470s–before Columbus visited the Caribbean. By the 1770s, there were plenty of children’s books, along with enough literate children to make good use of them.

Along the way–and beyond the frame of this article–we determine that children are worthy of their own education on a large scale, and that health care specific to childhood is a good idea, too.

Of course, I want to time travel, to talk to children and teenagers at the time they lived, in the places they lived. Even the best book on this subject–and this one is quite a good one–provides only snapshots and excerpts from earlier descriptions or diaries. Considering the great progress we have made on their behalf, I can only hope that someday, through some miracle of human genius, we’re able to travel back and understand the story more completely.

Three across, seats A, B, and C in a exit row. All three of us reading a book. The ten year old girl who happened to sit in the window seat: a fat novel by Rick Riordan. My wife: The One Hundred Mile Walk, now being released as a Helen Mirren motion picture. Me, a terrific long novel by New York City newspaper legend Pete Hamill, who writes about his city with street smarts and an appealing sense of mysticism.

Three across, seats A, B, and C in a exit row. All three of us reading a book. The ten year old girl who happened to sit in the window seat: a fat novel by Rick Riordan. My wife: The One Hundred Mile Walk, now being released as a Helen Mirren motion picture. Me, a terrific long novel by New York City newspaper legend Pete Hamill, who writes about his city with street smarts and an appealing sense of mysticism.

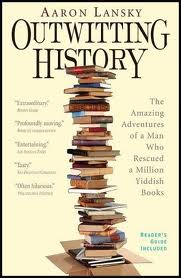

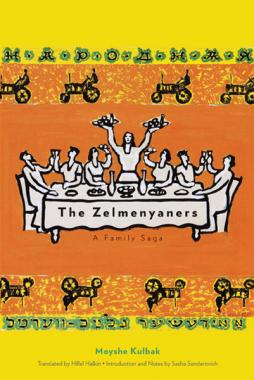

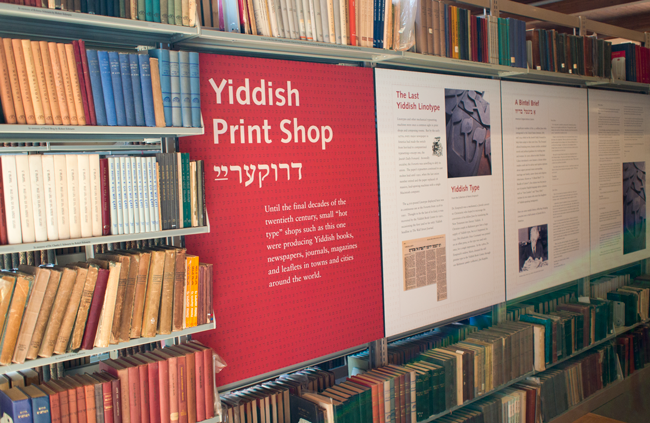

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.