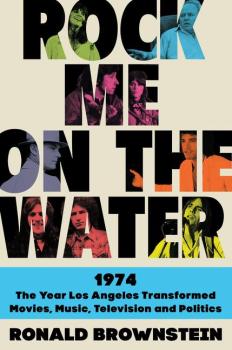

A good friend told me about a new book called Rock Me on the Water: 1974, The Year Los Angeles Transformed Movies, Music, Television and Politics. He was excited because we experienced some of the adventures that author Ronald Brownstein described, at least tangentially. It’s interesting to write about this particular book and this particular era because I happened to rewatch Almost Famous, Cameron Crowe’s film about his adventures on the road with The Allman Brothers Band (as a sixteen year old journalist for Rolling Stone, late 1973).

The book tells the story–a very good story at the start–about Linda Ronstadt and the way she built her career. This leads to background about David Geffen and the evolution of community of musicians in and around Laurel Canyon in the Los Angeles area. In short, they shared just about everything–life, love, shelter, food, drugs, music, songs, recording sessions, and a gigantic creative heart. In time, this culture evolves into a big-money enterprise, as evidenced by, for example, The Eagles, and the played-out sensibility so effectively described in their song, “Hotel California.” Indeed, this is music journalism at quite a high level, pleasant to read, deeply connected with outside events, evocative of time and place, and, viewed from the distance of time, something quite important. At the time, or shortly afterwards, I happened to be working (at a very junior level) at Warner Bros. Records in New York City. It was clear that everything had shifted west, but when the opportunity to move to Los Angeles came up, I turned it down. But I could sense that 1974 was right around the time when New York City lost a lot of ground as the center of the entertainment universe, and Los Angeles had gained what NYC had lost.

I come from a television background, but I had never thought much about how the development of Norman Lear’s sitcoms and Mary Tyler Moore’s small empire were related to this shift. I suppose I figured that sitcoms had always come from Los Angeles–for a long time, anyway–but I did not connect the creative energy in music to the creative energy in television. But there it is, and again, author Ronald Brownstein lays it all out in ways that suggest a much larger story.

And yes, there was a lot happening in the movie business at that time, too. All in Los Angeles. There was the old guard and the remains of the studio system, and Warren Beatty who seemed to be able to play both in the old ways and in the new. And there was Jack Nicholson, who was a somewhat awkward fit (mostly as a writer) but a far better fit for the independent orientation of the new. This, too, takes shape at around this time (1974 is a loose peg, but a good one). And much of what Brownstein describes is deeply connected to the larger shift in creative power.

But then, we meander into the “I wish I cared” world of Jane Fonda, Tom Hayden, and the very specific strange politics of the Vietnam era. The national material is good, if well-known, but the California politics is slow-going, and although the author tries very hard to connect the dots, that felt like a struggle. The politics of this era were all about the Vietnam War, but Los Angeles was tangential to the story. Unfortunately, the long story of Jerry Brown extends the book’s dull middle section before we see the light at the end of the tunnel–which turns out to be yet another motion picture screen, this time featuring the work of young Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. The story of the younger directors–Brian de Palma and Martin Scorsese among them–lifts the story back to a higher level, but now, the connections between their efforts, Los Angeles and the year become more diffuse.

The first half of the book is great fun, and somewhat provocative reading (as provocative as pop culture goes, I suppose). The second half contains interesting stories, but I lose the point of the book. Yes, I enjoyed reading about the development and success of M*A*S*H*, and the struggles between Carrol O’Connor (Archie Bunker) and Norman Lear, but neither really illuminates how and why Los Angeles and 1974 changed the world. We begin to see female directors, but that happens, mostly, later on. Here and there, we see some non-white faces and some non-white directors, and we do see “two hundred movies centers on Black characters” from 1971 until 1975, but the shift in Hollywood takes shape, in a meaningful and sustainable way, much later. Similarly, there are non-white recording artists and the beginning of a new segment in the industry, but the action here is in Memphis, Philadelphia, and soon after, in disco capitals throughout the U.S. It’s not really an L.A. thing, not that L.A. isn’t part of the story, it’s just that the book promises a deeper and more long-lasting connection.

The book regains some strength when it returns to Linda Ronstadt, whose story about career development is also not an L.A. thing. Her work with Peter Asher is more about her own independence and versatility as an artist (one who made a lot of money, who started her career in Los Angeles but then became full-scale U.S. star). Again, worth reading if you’re curious about Ronstadt and because she happens to be a very smart, wise, and talented artist–and in part, because she comes up as several other smart, wise and talented women are blazing their own paths. This, too, is partly tied to Los Angeles (Sherry Lansing becomes the first head of a major studio), but it’s also happening throughout the world at that time–and quite slowly, everywhere.

By “December” (each chapter is titled with the name of a month, but the months have nothing to do with the order or organization of the storytelling), everything is falling apart. ABC has out-maneuvered CBS, so the Norman Lear shows are losing ground to the likes of the fluffy-but-fun Happy Days on a newly competitive network. JAWS introduces the blockbuster film, leaving the rich potential of independent film in an early 1970s bucket that would take a long time to find its footing, and shifting priority of studio executives to a much better money-making proposition. Stadium shows took the place of small rock club performances–shifting the creative power back to NYC as punk and other alternative forms suddenly seemed a whole lot more interesting than anything that was going on in L.A. Fleetwood Mac, once an interesting band with blues roots and a critically acclaimed take on progressive rock, added Stevie Nicks, and became wildly popular among the stadium concert goers, and simply irritating for those who reveled in the early 1970s creative culture that was once, for a brief period, the center of the universe.

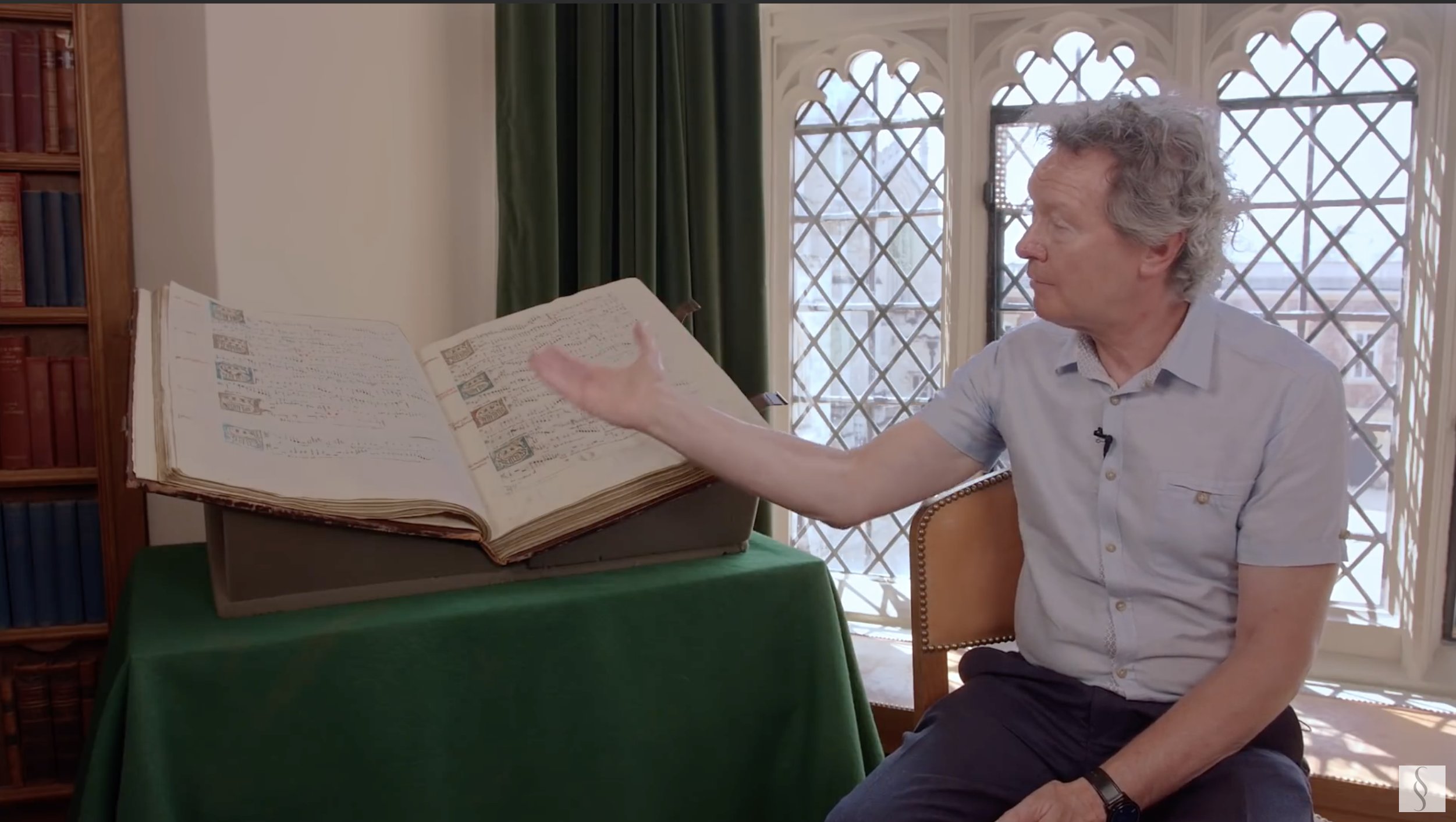

Spem in alium is the final entry in a

Spem in alium is the final entry in a  Renaissance Music. So much music, so little time–but then, much of this music has been performed for half a millennium. Regardless of my pace, it will survive. Today, in the hands and hearts of Harry Christophers, and his peers including John Eliot Gardiner, and others, it may be fair to say that it thrives as never before. The secret: these magical musicians are more than that. They are teachers. And I am their most willing student.

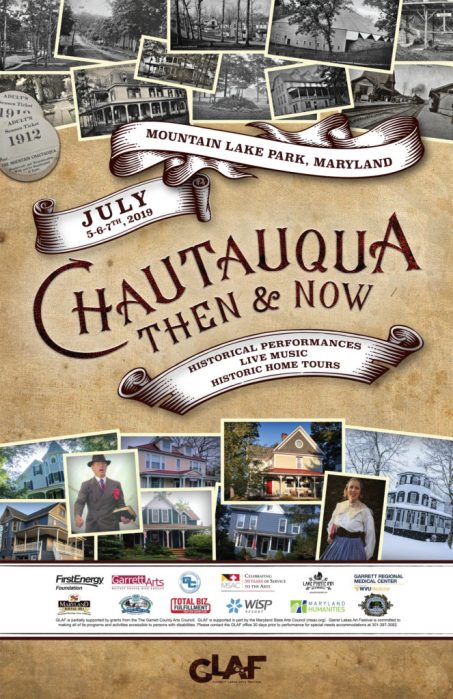

Renaissance Music. So much music, so little time–but then, much of this music has been performed for half a millennium. Regardless of my pace, it will survive. Today, in the hands and hearts of Harry Christophers, and his peers including John Eliot Gardiner, and others, it may be fair to say that it thrives as never before. The secret: these magical musicians are more than that. They are teachers. And I am their most willing student. The success of Third Fridays encouraged the city leaders to pursue a larger dream. They applied to serve as the host city for the

The success of Third Fridays encouraged the city leaders to pursue a larger dream. They applied to serve as the host city for the  We started out with an acoustic band out of Pittsburgh called

We started out with an acoustic band out of Pittsburgh called

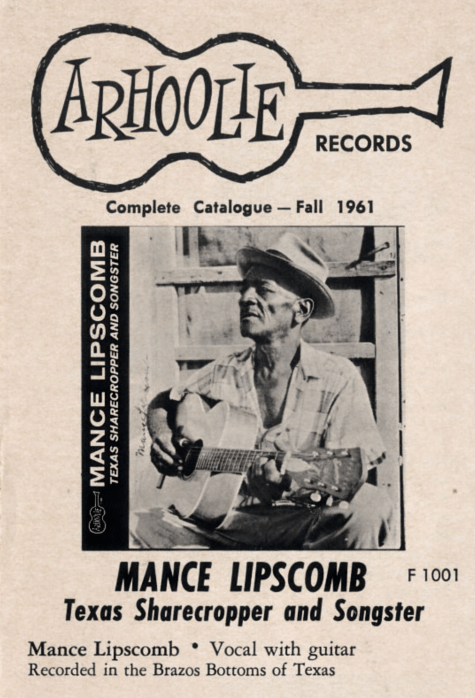

The variety of things to do at a folk festival is striking, and provocative. We wandered from Appalachian storytelling to the juke joint electric guitar of

The variety of things to do at a folk festival is striking, and provocative. We wandered from Appalachian storytelling to the juke joint electric guitar of

We missed them onstage, but we spent an hour chatting with the

We missed them onstage, but we spent an hour chatting with the