We all find our comfort zones, but every once in a while, it’s fun to try something new. For me, something new is, in fact, something quite old: a formulation of colored pastels that includes oil. Remember “Cray-Pas” from elementary school art class? I’m playing with the grown-up version, originally designed by Henri Sennelier, in Paris, in response to his friend Pablo Picasso’s request for oil paint that could be applied in stick form. Nearly seventy years later, Pastels à L’Huile, or Oil Pastels, continue to be a part of art supplier Sennelier’s product line. Since I enjoy working with pastels, I thought I’d try a boxed assortment of 24 oil pastels and consider the possibilities.

Unlike most media, oil pastels can be used to draw, paint or otherwise color on a remarkable range of surfaces including (but not limited to) paper, canvas, cardboard, wood, metal, plastic, or glass. And like watercolor pencils and watercolor sticks, oil pastels can provide the color in a mix with a solvent–essentially providing a very portable set of oil paints with minimalistic clean-up. They look, feel, and behave a bit like lipstick. Have a look at the video and you’ll see the possibilities.

The best way to get a sense of oil pastels is to buy a few a handful (visit Rochester Art Supply, or Dakota Pastels). For a basic introduction to the art and craft, I picked up a used copy of Oil Pastel for the Serious Beginner by John Elliot (I like other titles in this series, especially the ones about watercolor and pastels). You might also visit a few sites, like Eric Green’s Beginner’s Guide to Oil Pastels, or, even better, Explore Oil Pastels with Robert Sloan which is, easily, the best website about oil pastels in the world.

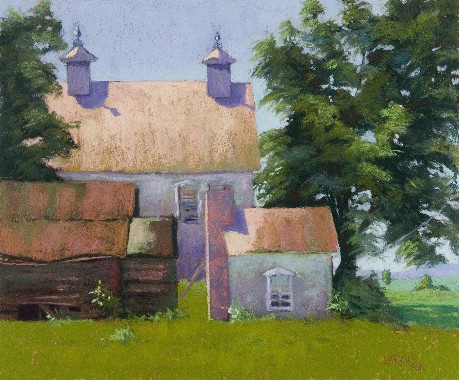

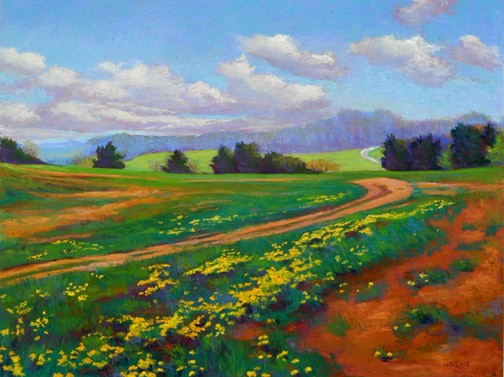

Sloan’s work with oil pastels is excellent. Below, two images from his website gallery, both already sold, but several equally handsome pieces are available.

Of course, there is nothing like getting your hands dirty. Sennelier’s set of 24 assorted oil pastels is just about right for the start–a spectrum mostly comprised of mid-tones, a bit lacking in lights and darks.

At the most basic level, you can use Sennelier oil pastels as you would crayons–an adult version of crayons, carefully isolating each stroke in the same way that some children keep their peas far away from anything else on the dinner plate. For graphic work, that’s a reasonable approach, but you lose out on some of the magical quality of oil pastels. These little guys (they really are fairly little) blend colors just beautifully–but you must use a very light touch to get the best possible effect. Once you start filling the surface’s texture with the pasty output, mixing and refinement becomes challenging.

I found a helpful way to practice, and refine my technique: I use “the wire side” (highly textured) of Canson’s reasonably inexpensive Mi-Teintes paper, and when I start filling the small pores in the paper with pigment, I have pressed too hard.

Another helpful note: the stickiness requires a special kind of attention. When blending, the stick picks up the blending color, so it’s not unusual to see a yellow oil stick with a film of, say, bright red or green. With dry pastels, you can usually wipe this off easily. With oil pastels, you must be vigilant, always keeping a lint-free bit of cloth nearby so you can wipe stray colors off the sticks. At first, this is annoying, but I got used to it.

Each stick is supplied in a paper wrapper–very useful to keep your hands clean, because the sticks become sticky and softish. But they do break inside the wrappers, and there’s not much you can do about that (then again, you can buy a larger, thicker version of Sennelier Oil Pastels, which may be preferable for some artists).

On and off for a year, I’ve been playing with these oil pastels. At first, I found them to be exceedingly difficult to control, an emotional return to my childhood frustration with Cray-Pas–just too thick, too rich, too everything for my comfort zone. In time, I came to understand the value of a lighter touch. Now, I find myself happy and content, mostly sketching and blending colors, every-so-softly, finding that I can experiment with color mixes with an immediacy and vivacity that’s not readily available in other media. It’s just plain fun to sketch with oil pastels, and if drift into nonrepresentational mode, so much the better. It’s tough for me to get a clear representation of a real life object with these sticks, but that’s why I use other media. It’s tough for me to enjoy the gentle abstraction that I find easy with oil pastels when I try to do the same with other media.

I tried a blending stick–Sennelier Oil Pastel # 221–and at first, I disliked rubbing what seemed like a white wax candle on my work. Then, I tried again, several more times, and I began to appreciate the way the blending stick pushes the vivid colors together. I can do the same with my finger with dry pastels, but the effect is different here (and, besides, finger blending with oil pastels, at least with my fingers, makes an awful mess).

All of which makes me admire the sample work from Robert Sloan even more. I am not yet at a point where I can exert real control over the strokes–and when I see the precision that he achieved on his big cat drawing, I feel good because I know that it is possible for a human being to exert that kind of control on what are, so far, tools that I have not yet mastered.

That’s the fun, of course. If you already know how to do something, maybe there’s not much opportunity to learn. Right now, I am just a beginner, and I celebrate the frustration, the sheer joy in knowing that I can and will learn, and develop at least a modest form of mastery over what amounts to a sophisticated version of crayons (in the best professional sense of the term).

Samples of my work? Perhaps in a few years. For now, I’m happy as a beginning student in a new medium. No need to embarrass myself. I’m learning a lot, and I’m reporting my progress. And doing my best to spread the knowledge I’m gaining along the way.

Another thing I’ve learned about myself (though I suppose this is common to others, too): I am always drawn to collections of bright colors across the spectrum, but these sets are not always the best choice for learning about a new medium. Lights and darks make all the difference, so I will soon be enhancing my basic spectrum set. For those with a bit of money and a sense of adventure, two other sets are probably a better place to begin than the 24 Assorted selection–the wood box set of 50 “Original Picasso Colors” (on sale at Fine Art Store for $117), or, for $50-60 more, the set of 72 colors in a nice cardboard box (Fine Art Store: $173). Both include a useful mix of light, mid and dark tones–of course, the 72 set is preferable. Or, you can just buy a handful of whatever oil pastels you’d like–Sennelier products are widely distributed throughout the world. Just visit a good art supply store.

Sennelier is not the only company offering portable oil sticks–Holbein sells a very wide range of colors (224 to Sennelier’s 120), and Cretacolor sells a similar product under the name AquaStics, which are water soluble. Winsor & Newton sells much larger and thicker Oil Bars–with a different formulation that categorizes their product as more closely related to oil paints in solid form, less aligned with oil pastels (“Don’t mistake them for oil pastels, though – Oilbars are made to a special formulation of linseed or safflower oil and wax.”–from the company’s website). Sennelier also makes and sells oil sticks.