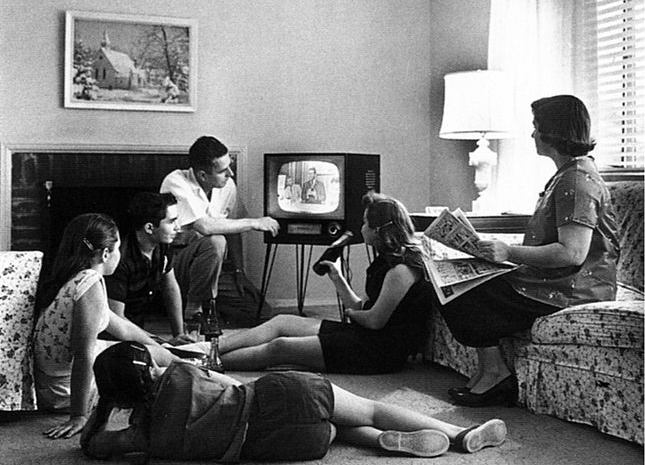

The old ratio was 3 by 4: a reliable compression of reality, the extra window in every household that looked out at the world. It offered a limited view, controlled by powerful producers and directors, versatile performers, intense journalists who learned the trade by explaining why and how the Germans were bombing the guts out of London during World War II. Very few people were allowed to put anything into that window: NBC, CBS, ABC and a few local television companies controlled every minute of the broadcast day. It was radio with pictures, a new medium that learned its way through visual storytelling when the only colors were shades of grey.

The old ratio was 3 by 4: a reliable compression of reality, the extra window in every household that looked out at the world. It offered a limited view, controlled by powerful producers and directors, versatile performers, intense journalists who learned the trade by explaining why and how the Germans were bombing the guts out of London during World War II. Very few people were allowed to put anything into that window: NBC, CBS, ABC and a few local television companies controlled every minute of the broadcast day. It was radio with pictures, a new medium that learned its way through visual storytelling when the only colors were shades of grey.

The new ratio is 16:9, and it seems to accommodate just about anything anybody wants to place in that frame. And the frame travels with us everywhere: on phones, tablets, on Times Square, on airliners and in half the rooms of our homes. In offices, too. There is little cultivation or careful decision making. If you want to make a video, you point your phone at anything you please, press record, and then, fill the frame with stuff that moves and makes noise.

The more video that YouTube releases—that would be 100 new hours of material every minute of our modern lives—the less I pay attention. I am overwhelmed. I cannot keep up with the two dozen new websites or apps or YouTube videos that friends and colleagues supply with the very best of attentions. I am fascinated by the range of material, frustrated because the lack of a professional gatekeeper means I must be my own programmer, and I just don’t have the time or interest in doing that every day. I want curation. I want the 21st century equivalent of a television channel, just for me. I don’t want to watch pre-roll commercials, and I don’t want to “skip this ad in 5 seconds.”

As curmudgeonly as this may feel, I think I’m happier reading a book. In fact, as media abundance increases, I find myself withdrawing into a very different series of rectangles—ones that don’t include advertising, don’t include pictures, don’t move or make noise. I’m now buying books by the half dozen—about as many as I can carry out of the increasingly familiar gigantic book sales that offer perfectly good volumes for one or dollars a piece.

I like the idea that the person who wrote the book is either an expert in his or her field—otherwise, the publisher never would have agreed to the scheme—or a superior storyteller—one that the editors, and the publisher, deemed worthy. I love the idea that the author writes the book and then hands it off to a professional editor, one with literary taste and an eye for clear, precise phrasing, and that the book then goes through yet another reading by a copy editor who makes sure the words and sentences are provided in something resembling proper English usage, and that, after the book is typeset, another editorial staff member proofreads the whole book and causes any number of errors to be corrected. When the book reaches my hands, I am confident that the work is, at least, well-manufactured.

Might it be any good? At a dollar or two, I’m not sure I care, but I do choose my books, and my authors, with care. Somehow, I feel that my side of the contract is to spend a bit of time selecting, just as I do before I decide that I should devote two hours of my life watching a motion picture.

When I find a wonderful film—not always easy, but always worth the effort—and it fills a 60-inch Samsung plasma screen with magic—I am thrilled. Most often, those wonderful films are made by people in other countries, or by smaller companies in the USA, or by animators. Just as it’s unusual for me to stumble into something wonderful in the land of books that is newly released, the films I watch are usually a few years old. Not really old, though those are fun, too, but old enough that I can get a sense of whether they had any staying power beyond the echo of their opening weekend. I was happily surprised by the depth of the storytelling when I watched Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks pretend they were P.L. Travers and Walt Disney during “Saving Mr. Banks,” for example. Do I care that a film was an Academy Award contender this year? Not really, but when I see the words Pulitzer Prize or Man Booker Prize on a rectangular book cover, I always give it a second look. There is a qualitative difference, I suppose, even if it exists only in my own prejudiced, confused, 20th/21th century mind.

What about flimsier rectangles? Magazines remain interesting, and it’s difficult for me to get on a train without finding something I want to read at the newsstand before boarding. Whether it’s The Atlantic, The Economist, The New Yorker, Harper’s, MIT Technology Review, or a dozen others, I sense that I am reading the work of a well-organized editorial culture, and that is presented in a form that suggests substance. When I read an article on a screen, the medium itself feels temporary, and rarely impresses me with the gravitas, or the well-honed humor, that these magazines (okay, some of these magazines) routinely provide.

The other flimsy rectangle—very, very flimsy in its form, in fact—is the newspaper. Sadly, few local newspapers possess the resources or clarity of focus that they did decades ago. Their industry has been devastated by technology and wickedly poor leadership decisions. Then again, there is still nothing better than reading The Sunday New York Times for half of the weekend, often with enough left over for Monday, or maybe, Tuesday morning, too. Except, perhaps, a good fresh New York bagel beside the paper. In a pinch, I can find similar joy in the morning with the Boston Globe, The Washington Post, the International Herald Tribune, or whatever quality paper is nearby when I’m away from home. The Wall Street Journal’s weekend edition is every bit as good; after I finish today’s Times, I will work my way through the remaining sections of my new Sunday habit.

Interactive rectangles are something else again. Tablets, and smart phones, are wonderful, and I use them every day, but mostly for media creation (I write this blog, etc.) than for reading (eBooks, HuffPost, etc.). If I want to read, to seriously read, I guess I’ve learned to prefer it in print. And if I want to watch a movie, or a TV show, unless I’m on a train or plane, I would just as soon watch it in a comfortable chair with a nice large screen to fill part of a family room wall, and not listen to it through dinky speakers or a less-than-comfy headset or earplugs.

Who cares? Not sure, but I thought I’d put some ideas on a digital screen that I, for one, would prefer to read in another medium. Since that other medium has gatekeepers, and because few print publishers would allow me to zig from media theory to watercolors to interest gadgets to public poverty policy, then zag to book reviews or notes about recent jazz CDs that I think you should buy, I’m happy writing into a glass box, and I hope that doesn’t cause you too much inconvenience or discomfort.

Sorry to go so long this time. Without an editor, or an editorial hole to fill (love that term), I just wrote until I felt I had made said my piece.

Done.