In 1969, most people, even those who were following the progression from jazz to fusion, hadn’t yet heard the work of a British guitar player named John McLaughlin. That was the year that he recorded his first album, “Extrapolation.” At the time, it was wildly experimental, but as I listen to it in the background while writing this article, it’s really delightful, gentle, meditative, not at all explosive. McLaughlin is a gifted guitar player and composer. He shares the stage with an another young British musician, a man who plays the somewhat unusual combination of soprano and baritone sax. His name is John Surman. At the time, Surman was already recording on his own for the Deram label (later famous for Moody Blues LPs). As a guy who tended to read album liner notes, I probably made a mental note about how much I enjoyed Surman’s work, but that’s didn’t amount to much.

In 1969, most people, even those who were following the progression from jazz to fusion, hadn’t yet heard the work of a British guitar player named John McLaughlin. That was the year that he recorded his first album, “Extrapolation.” At the time, it was wildly experimental, but as I listen to it in the background while writing this article, it’s really delightful, gentle, meditative, not at all explosive. McLaughlin is a gifted guitar player and composer. He shares the stage with an another young British musician, a man who plays the somewhat unusual combination of soprano and baritone sax. His name is John Surman. At the time, Surman was already recording on his own for the Deram label (later famous for Moody Blues LPs). As a guy who tended to read album liner notes, I probably made a mental note about how much I enjoyed Surman’s work, but that’s didn’t amount to much.

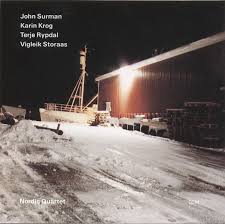

Jumping far forward in time, all the way to 1995, I was writing a book for Billboard about the story of jazz, told through about 500 of the best jazz CDs. I worked with every jazz label, and welcomed their suggestions. Some of the most intriguing jazz CDs came from a European label, ECM Records. The music on ECM differed from the work on other labels: it was sophisticated, experimental, as much a soundscape work of art as a record album. One of the most intriguing of the ECM recordings was made by the Nordic Quartet, led by John Surman. I’m listening to the first track, and I can easily understand why it caught and captured my attention. Surman and his electric guitar partner Terje Rypdal had so thoroughly updated the explorations of the “Extrapolation” era. Weaving through the first track,  Traces, there is a deep female voice whose sound more closely resembles an instrument than an upfront vocalist—and she’s singing phrases that feel more like poetry than lyrics. She was not credited as a singer, but instead, as “voice.” Her name is Karin Krog.

Traces, there is a deep female voice whose sound more closely resembles an instrument than an upfront vocalist—and she’s singing phrases that feel more like poetry than lyrics. She was not credited as a singer, but instead, as “voice.” Her name is Karin Krog.

By this time, I was very well organized, and my note about finding more Karin Krog music stayed with me for (yikes) nearly twenty years. I liked what I heard, but in time, I forgot where I heard her voice. I’d visit my favorite deep inventory record stores, and nobody had ever heard of her.

Over time, I continued to collect John Surman CDs, and loved most of them. (Note to myself: I need to update my Surman collection because all of the CDs I just fetched from the shelf pre-date 2003), but there was no mention of Karin Krog on any of them.

Earlier this year, late at night, I decided to do a Google Search on Karin Krog. Bingo! She released her first single in 1963! (Clearly, I have missed a very good story that spans lots of decades.) We connected, and she was kind enough to send a few CDs. While the package was in transit from Europe, I found an LP called “Some Other Spring” in a used record store, copyright 1970, by Karin Krog and the brilliant Dexter Gordon (with the equally formidable Kenny Drew on keyboards, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen on bass—they were working together in a Copenhagen jazz club). I was impressed by the good company, but I was a initially disappointed because the magical soundscape I had so enjoyed on Nordic Quartet was absent here; then, I listened more carefully, and with more of an open mind, and began to understand her versatility (it was her plaintive version of Jobim’s “How Insensitive” that won me over). As the CDs were making their way to me, I explored the depth and breadth of a discography that includes dozens of albums.

Earlier this year, late at night, I decided to do a Google Search on Karin Krog. Bingo! She released her first single in 1963! (Clearly, I have missed a very good story that spans lots of decades.) We connected, and she was kind enough to send a few CDs. While the package was in transit from Europe, I found an LP called “Some Other Spring” in a used record store, copyright 1970, by Karin Krog and the brilliant Dexter Gordon (with the equally formidable Kenny Drew on keyboards, Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen on bass—they were working together in a Copenhagen jazz club). I was impressed by the good company, but I was a initially disappointed because the magical soundscape I had so enjoyed on Nordic Quartet was absent here; then, I listened more carefully, and with more of an open mind, and began to understand her versatility (it was her plaintive version of Jobim’s “How Insensitive” that won me over). As the CDs were making their way to me, I explored the depth and breadth of a discography that includes dozens of albums.

The CDs arrived. I decided to listen in chronological order, so I started with what I now understand to be a work from the mid-1970s (fitting nicely into my story), an album called “Cloud Nine Blue.” Gosh, it’s rich! (The liner notes from the modern re-release mention something about remixing—completely unnecessary!). So here’s the incredible depth of John’s bass clarinet intermingled with lines of synthesizer and the siren qualities of Karin’s voice, accents and filagree from John’s soprano sax, a kind of avant-garde meets religious exaltation on “Eyeless in Movement,” no lyrics, just sonic expression, then a half-spoken, half-sung song from Karin. Gee, this is interesting music, the kind of work that makes a top-quality sound system worth the investment so each of the artists’ ideas are allowed to fully show themselves (listening on a lesser system is fine, but you’re missing half the show).

Jumping to “Oslo Calling,” it’s now 2008. The execution is cleaner, more modern (heck, it’s more than thirty years later!), somewhat more traditional in its jazz arrangements. Karin’s voice has gained luster in the lower ranges, and boundless confidence. When a song is a soundscape, it’s slicker, less experimental, and I miss the freer thinking of the earlier work (but musicians must evolve, and the range of both John and Karin has been remarkable, over so many years). I especially enjoyed “Three Little Words,” a Kalmar-Ruby tune that’s been forgotten by too many performers—her interpretation is sassier than the others I’ve heard.

Jumping to “Oslo Calling,” it’s now 2008. The execution is cleaner, more modern (heck, it’s more than thirty years later!), somewhat more traditional in its jazz arrangements. Karin’s voice has gained luster in the lower ranges, and boundless confidence. When a song is a soundscape, it’s slicker, less experimental, and I miss the freer thinking of the earlier work (but musicians must evolve, and the range of both John and Karin has been remarkable, over so many years). I especially enjoyed “Three Little Words,” a Kalmar-Ruby tune that’s been forgotten by too many performers—her interpretation is sassier than the others I’ve heard.

Of the three CDs, the most interesting is also the most experimental, a cycle of songs originally composed for a 2010 jazz festival. It’s called “Songs About This and That,” and I like it because it recalls my earlier interest in their exuberant experimental side, but places it in a more artful, more carefully arranged setting. There is a sense of open time and space to explore, to allow for long lines, an ease with the maturation of Karin’s voice. On this CD, I think my favorite track may be “Cherry Tree Song” because the poetic lyrics wind so gracefully around John’s baritone sax and bass clarinet, a warm combination of electric guitar, vibraphone, and John’s bass recorder. In fact, I jotted down some other favorite tracks, and found the list was too long to manage, but I will mention the vibe solo that begins “Moonlight Song” and Karin’s waking-up voice, looking backward on memory. Wrapping up an article I’ve so enjoyed writing, I happened to notice that Karin’s credit on this CD is what it was so many years before, not “vocals” but simply, “voice.”

Of the three CDs, the most interesting is also the most experimental, a cycle of songs originally composed for a 2010 jazz festival. It’s called “Songs About This and That,” and I like it because it recalls my earlier interest in their exuberant experimental side, but places it in a more artful, more carefully arranged setting. There is a sense of open time and space to explore, to allow for long lines, an ease with the maturation of Karin’s voice. On this CD, I think my favorite track may be “Cherry Tree Song” because the poetic lyrics wind so gracefully around John’s baritone sax and bass clarinet, a warm combination of electric guitar, vibraphone, and John’s bass recorder. In fact, I jotted down some other favorite tracks, and found the list was too long to manage, but I will mention the vibe solo that begins “Moonlight Song” and Karin’s waking-up voice, looking backward on memory. Wrapping up an article I’ve so enjoyed writing, I happened to notice that Karin’s credit on this CD is what it was so many years before, not “vocals” but simply, “voice.”

A lifetime of work. So much fun to discover, to listen attentively because there is so much to hear.Thanks, John, thanks, Karin. I want to hear more.