Conventional public schools are “arranged to make things easy for the teacher who wishes quick and tangible results.” Furthermore, “the ordinary school impress[es] the little one into a narrow area, into a melancholy silence, into a forced attitude of mind and body.” No doubt, you’ve had a thought similar to this one: “if we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow.”

Conventional public schools are “arranged to make things easy for the teacher who wishes quick and tangible results.” Furthermore, “the ordinary school impress[es] the little one into a narrow area, into a melancholy silence, into a forced attitude of mind and body.” No doubt, you’ve had a thought similar to this one: “if we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow.”

There’s a reason for the old school language. The words were published in 1915 by educator John Dewey. A century later, the situation has begun to change, mostly, according to Brookings Institute vice president Darryl M. West, as a result of the digital revolution. Mr. West advances this theory by offering an ample range of examples in his new book, Digital Schools.

Quite reasonably, he begins by considering various attempts at school reform, education reform, open learning, shared learning, and so on. Forward-thinking educators fill their office shelves with books praising the merits of each new wave of reform, and praise the likes of Institute for Play, but few initiatives taken hold with the broad and deep impact that is beginning to define a digital education.

Blogs, wikis, social media, and other popular formats are obvious, if difficult to manage, innovations more familiar in student homes than in most classrooms, but the ways in which they democratize information–removing control from the curriculum-bound classroom and teacher and allowing students to freely explore–presents a gigantic shift in control.

Blogs, wikis, social media, and other popular formats are obvious, if difficult to manage, innovations more familiar in student homes than in most classrooms, but the ways in which they democratize information–removing control from the curriculum-bound classroom and teacher and allowing students to freely explore–presents a gigantic shift in control.

Similarly, videogames and augmented reality, whether in an intentionally educational context or simply as a different experience requiring critical thinking skills in imaginary domains, are commonplace at home, less so in class, and, increasingly, the stuff of military education, MIT and other advanced academic explorations, and, here and there, the charge of a grant-funded program at a special high school. More is on the way.

Evaluation, assessment, measurement–all baked into the traditional way we think about school–are far more efficient and offer so many additional capabilities. No doubt, traditional thinkers will advance incremental innovation by mapping these new tools onto existing curriculum, perhaps a step in the right direction, however limited and short-sighted those steps may be. The big step–too large for most contemporary U.S. classrooms–is toward personalized learning and personalized assessment, but that would shift the role of the teacher in ways that some union leaders find uncomfortable.

The power behind West’s view is, of course, the velocity of change in the long-promising arena of distance learning. During the past ten years , the percentage of college students who have taken at least one distance learning course has tripled, and passed 30 percent in 2011. Numbers are not available, but I suspect we’ve now passed the 50 percent mark. The book does not address the stunning growth of, for example, Coursera. Kevin Werbach, a Wharton faculty member, taught over 85,000 students in his first Coursera course (on gamification)–students from all of the world. Indeed, the current run rate is 1.4 million new Coursera sign-ups per month.

Mimi Ito is one of the more influential thinkers about modern education and its future. Click to read her bio.

The author quotes education researcher Mimi Ito:

There is increasingly a culture gap between the modes of delivery… between how people learn and what is taught. [In addition to] the perception that classrooms are boring… students [now] ask, ‘Why should I memorize everything if I can just go online? … Students aren’t preparing kids for life.”

Is this a ground-breaking book. No, but it is useful compendium of the digital changes that are beginning to take root in classrooms across America. Yes, we’re behind the times. In many ways, students are far ahead of the institutions funded to teach them. The book serves notice: no longer are digital means experimental. Computer labs are being replaced by mobile devices. Students are taking courses from the best available teachers online, and not only in college. Many students are enrolled nowhere; they are simply taking courses because they want to learn or need to learn for professional reasons. Without formal enrollment, institutions begin to lose their way. The structure is beginning to erode. Just beginning. And it can be fixed, changed, transformed, amended, and otherwise modernized. And so, the helpful author provides an extensive list of printed links for interesting parties to follow.

Just out of curiosity, I called up Darrell M. West’s web page–it’s part of the Brookings Institution’s site–and, as I expected, he is a man of consider intellect and accomplishment. And so, I hoped I would find the above-cited links as a web resource. I looked for Education under his extensive list of topics of interest but it wasn’t there. (Uh-oh?) I did find a section on his page called “Resources,” but the only available resource on that page was a 10MB photograph of Mr. West. I couldn’t find the links anywhere. Perhaps this can be changed so that all readers, educators and interested parties can make good use of his forward-thinking work.

Sorry–one more item–I just found a recent paper by Dr. West, and I thought you might find both the accompanying article and the link useful.

Here’s a look at 42-year-old John Dewey in 1902. To learn more about him, click on the picture and read the Wikipedia article.

This year, there are slightly fewer than 50 million public school students, including about 15 million high school students in public school. Add another 5 million students in private school, including over 1 million in private high schools.

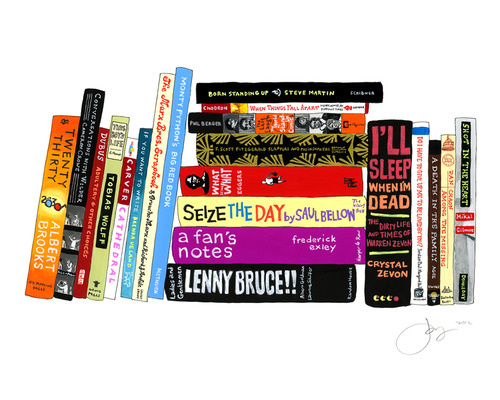

This year, there are slightly fewer than 50 million public school students, including about 15 million high school students in public school. Add another 5 million students in private school, including over 1 million in private high schools. Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh.

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh. James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

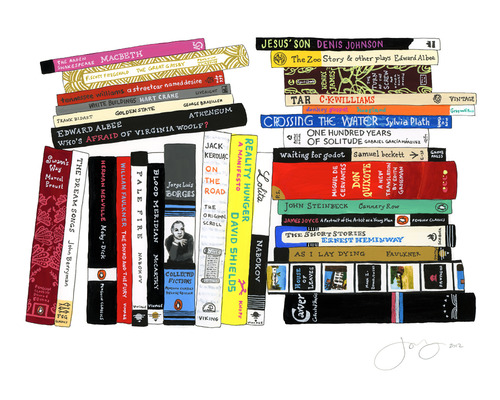

James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

![(Copyright 2006 by Zelphics [Apple Bushel])](https://diginsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/apple_bushel.png?w=660)

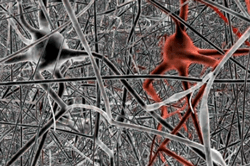

Much of Kurzweil’s theory grows from his advanced understanding of pattern recognition, the ways we construct digital processing systems, and the (often similar) ways that the neocortex seems to work (nobody is certain how the brain works, but we are gaining a lot of understanding as result of various biological and neurological mapping projects). A common grid structure seems to be shared by the digital and human brains. A tremendous number of pathways turn or or off, at very fast speeds, in order to enable processing, or thought. There is tremendous redundancy, as evidenced by patients who, after brain damage, are able to relearn but who place the new thinking in different (non-damaged) parts of the neocortex.

Much of Kurzweil’s theory grows from his advanced understanding of pattern recognition, the ways we construct digital processing systems, and the (often similar) ways that the neocortex seems to work (nobody is certain how the brain works, but we are gaining a lot of understanding as result of various biological and neurological mapping projects). A common grid structure seems to be shared by the digital and human brains. A tremendous number of pathways turn or or off, at very fast speeds, in order to enable processing, or thought. There is tremendous redundancy, as evidenced by patients who, after brain damage, are able to relearn but who place the new thinking in different (non-damaged) parts of the neocortex.

Third in the trilogy is the bright red volume, The Psychology Book. As early as the year 190 in the current era, Galen of Pergamon (in today’s Turkey) is writing about the four temperaments of personality–melancholic, phlegmatic, choleric, and sanguine. Rene Descartes bridges all three topics–Philosophy, Economics and Psychology overlap with one another–with his thinking on the role of the body and the role of the mind as wholly separate entities. We know the name Binet (Alfred Binet) from the world of standardized testing, but the core of his thinking has nothing whatsoever to do with standardized thinking. Instead, he believed that intelligence and ability change over time. In his early testing, Binet intended to capture a helpful snapshot of one specific moment in a person’s development. And so the tour through human (and animal) behavior continues with Pavlov and his dogs, John B. Watson and his use of research to build the fundamentals of advertising, B.F. Skinner’s birds, Solomon Asch’s experiments to uncover the weirdness of social conformity, Stanley Milgram’s creepy experiments in which people inflict pain on others, Jean Piaget on child development, and work on autism by Simon Baron-Cohen (he’s Sacha Baron Cohen’s cousin).

Third in the trilogy is the bright red volume, The Psychology Book. As early as the year 190 in the current era, Galen of Pergamon (in today’s Turkey) is writing about the four temperaments of personality–melancholic, phlegmatic, choleric, and sanguine. Rene Descartes bridges all three topics–Philosophy, Economics and Psychology overlap with one another–with his thinking on the role of the body and the role of the mind as wholly separate entities. We know the name Binet (Alfred Binet) from the world of standardized testing, but the core of his thinking has nothing whatsoever to do with standardized thinking. Instead, he believed that intelligence and ability change over time. In his early testing, Binet intended to capture a helpful snapshot of one specific moment in a person’s development. And so the tour through human (and animal) behavior continues with Pavlov and his dogs, John B. Watson and his use of research to build the fundamentals of advertising, B.F. Skinner’s birds, Solomon Asch’s experiments to uncover the weirdness of social conformity, Stanley Milgram’s creepy experiments in which people inflict pain on others, Jean Piaget on child development, and work on autism by Simon Baron-Cohen (he’s Sacha Baron Cohen’s cousin).