I am beginning to read what Ellen Willis wrote. Some of it is familiar, but I lost track of her sometime last in the last century. She wrote about the counter culture, and, apparently, continued on that path long after everyone else had moved on. Willis was an extraordinarily clear thinker about things that matter. That clarity, and her passion, and her just-plain-good writing are the reasons why I will spend the winter reading every one of about fifty articles and essays in a book that her daughter Nona put together. It’s called “The Essential Ellen Willis.” I’m guessing you won’t find it in many bookstores despite the best efforts of the University of Minnesota Press, but it’s certainly available online. For someone who enjoys smart writing with more than a small dose of social conscience, it’s an ideal holiday choice.

was an extraordinarily clear thinker about things that matter. That clarity, and her passion, and her just-plain-good writing are the reasons why I will spend the winter reading every one of about fifty articles and essays in a book that her daughter Nona put together. It’s called “The Essential Ellen Willis.” I’m guessing you won’t find it in many bookstores despite the best efforts of the University of Minnesota Press, but it’s certainly available online. For someone who enjoys smart writing with more than a small dose of social conscience, it’s an ideal holiday choice.

Lots and lots of interesting material about Ellen on this Tumblr page. To go there, click on the picture.

Who was she? Ellen Willis was born in 1941 and died in 2006. She was the first rock critic for The New Yorker, a columnist who wrote regularly for the Village Voice, and an educator at New York University (she founded the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program). She was a feminist, and an authentic, long-term voice for what was, in the 1960s and 1970s, a movement, and became, in the 1980s and 1990s, a reasoned approach to social outrage. Her daughter Nona, who caused Willis such consternation about her own feminist place as a mother, is the protagonist in one of this book’s best articles, a Voice column entitled “The Diaper Manifesto.” Grown up, Nona Willis Aronowitz is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute, an author, and, now, the compiler and editor of her mom’s best stuff. (This is the second effort: the first collected Willis’s rock articles and criticism in a book called “Out of the Vinyl Depths” from the same publisher.)

I wasn’t sure where to start navigating 536 pages of a writer’s collected work, so I started with an article about Bob Dylan that she wrote for Cheetah in 1967. Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” was a new release, nearly two years after his serious motorcycle accident. It’s been nearly fifty (!) years since she wrote the article. She starts at the beginning, assessing the emerging folk music scene and his place in it:

When Bob Dylan first showed up at Gerde’s [Folk City] in the spring of 1961, fresh skinned and baby faced, and wearing a school boy’s corduroy hat, the manager asked him for proof of age. He was nineteen only recently arrived in New York. Skinny, nervous, manic, the bohemian patina of jeans and boots, scruffy hair, hip jargon and hitchhiking mileage barely settled on nice Bobby Zimmerman, he has been trying to catch on at the coffeehouses. His material and style were a cud of half-digested influences: Guthrie-cum-Elliot, Blind Lemon Jefferson-cum-Leadbelly-cum-Van Ronk, the hillbilly sounds of Hank Williams and Jimmy Rodgers; the rock-and-roll of Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley. He was constantly writing new songs. Onstage, he varied poignancy with clownishness. His interpretations of traditional songs—especially blues—were pretentious, and his harsh, flat voice kept slipping over the edge of plaintiveness into strident self-pity. But he shone as a comedian, charming audiences with Charlie Chaplin routines, playing with his hair and his cap, burlesquing his own mannerism and simply enjoying himself.”

From July, 1986’s “The Diaper Manifesto,” which begins with Willis exploring her conflicted feelings about hiring someone to care for her child so that she can continue to write…

Before I had a child, I had lots of opinions on the subject. Two years afterward, some of them have stuck with me: I’m still convinced that staying home full-time with a healthy, rambuctious kid would turn me into squirrel food, that child care should be as much men’s job as women’s, that communal child rearing in some form holds the most hope of resolving the collision between adults’ and children’s needs, as well as the emotional cannibalism of the nuclear family. But for the most part, figuring out what kind of care best meets my daughter’s needs has been—continues to be—a processing of disentangling prejudice from experience.”

Progress is made.

“In the end, we hired a Haitian woman who, as a friend drily put it, ‘fit the demographic profile for the job’ and quickly put to shame all my stereotypes. Without the benefit of higher education, middle class choices, or green card, Philomese had all the psychological smarts I could ask for and tended to the baby with love and imagination…Quite aside from our own needs as working parents, Nona was clearly better off having an intimate daily relationship with another adult.”

From September 2009, outrage and clear thinking about the drug war:

According to the drug warriors, I and my ilk are personally responsible not only for the death of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix but for the crack crisis. Taken literally,, this is scurrilous nonsense: the counterculture never looked kindly on hard drugs, and the age of crack is a product not of the 60s but of Reaganism. Yet there’s a sense in which I do feel responsible. Cultural radicals are committed to extending freedom, and that commitment, by its nature, is dangerous. It encourages people to take risks, some of them foolish or worse….If I support the struggle for freedom, I can’t disclaim responsibility for its costs. I can only argue that the cost of suppressing freedom are, in the end, far higher. All wars are hell. The question is which ones are worth fighting.”

He’s a theater director and choreographer with a list of impressive, and recent,

He’s a theater director and choreographer with a list of impressive, and recent,

Okay, more about Jules before begin. Actually, you get a fair sense of him from his 2008 cartoon for NYC’s Village Voice. I found it on Wikipedia. He won a Pulitzer Prize for political cartooning, was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Writer’s Guild of America, and he’s got his place in the Comic Book Hall of Fame. And now, he’s got this new book.

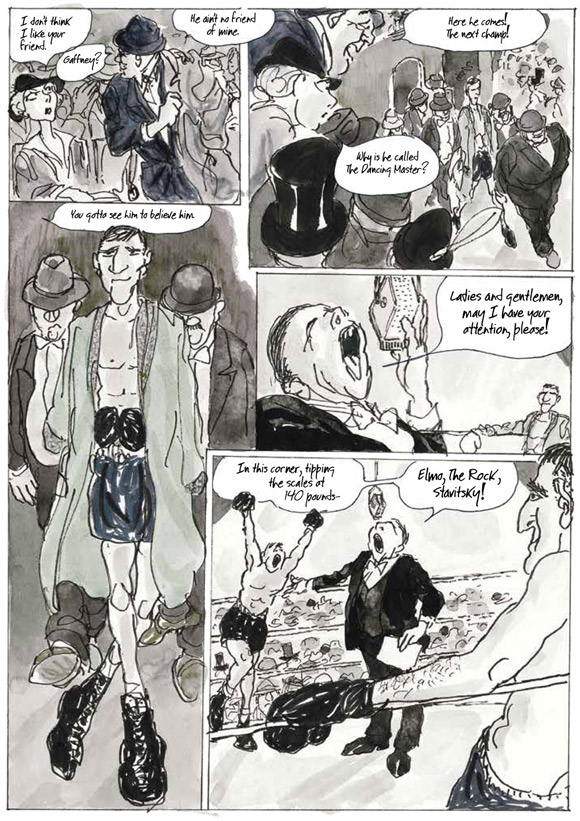

Okay, more about Jules before begin. Actually, you get a fair sense of him from his 2008 cartoon for NYC’s Village Voice. I found it on Wikipedia. He won a Pulitzer Prize for political cartooning, was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Writer’s Guild of America, and he’s got his place in the Comic Book Hall of Fame. And now, he’s got this new book. In theory, it’s the book that drives the story, but in practice, here, it’s the pictures. Actually, it’s the whole page, the whole well-designed, elegantly organized duotone watercolors and pen-and-ink that feel so dark, so thick with intrigue. Most of the book is rendered in sepia—not the old tones of photographs, but lively, contrasty, vaguely seedy renditions of what otherwise might have been black. The accent is usually a very pale green, the color of a Hollywood swimming pool on page, a cadaver on the next.

In theory, it’s the book that drives the story, but in practice, here, it’s the pictures. Actually, it’s the whole page, the whole well-designed, elegantly organized duotone watercolors and pen-and-ink that feel so dark, so thick with intrigue. Most of the book is rendered in sepia—not the old tones of photographs, but lively, contrasty, vaguely seedy renditions of what otherwise might have been black. The accent is usually a very pale green, the color of a Hollywood swimming pool on page, a cadaver on the next.

To begin, think not about the objects, but about our desires. We want to know it all—but not all of the time. Sometimes, we just want to know whether it’s cold outside, or whether the dog has been fed. We don’t know the details, don’t really need to know the precise temperature or the moment in time when the dog’s bowl was filled with food. So instead of a thermometer, or, more intensely, a digital thermometer that reports temperature to the tenth of a degree, how about a glowing orb? Or, as author-scientist-innovator-professor David Rose describes his invention, an Ambient Orb. He writes, in his new-ish book, Enchanted Objects, “They aren’t disruptive. They have a calm presence. They don’t require you to do anything…They are there, in every room of the house with the exact information you expect from them.” So he reimagined a crystal ball that contains LEDs that change color, and report the information you need by glowing in your choice of hues. “As the colors change, you glance and know if the pollen count in the air is higher than usual.”

To begin, think not about the objects, but about our desires. We want to know it all—but not all of the time. Sometimes, we just want to know whether it’s cold outside, or whether the dog has been fed. We don’t know the details, don’t really need to know the precise temperature or the moment in time when the dog’s bowl was filled with food. So instead of a thermometer, or, more intensely, a digital thermometer that reports temperature to the tenth of a degree, how about a glowing orb? Or, as author-scientist-innovator-professor David Rose describes his invention, an Ambient Orb. He writes, in his new-ish book, Enchanted Objects, “They aren’t disruptive. They have a calm presence. They don’t require you to do anything…They are there, in every room of the house with the exact information you expect from them.” So he reimagined a crystal ball that contains LEDs that change color, and report the information you need by glowing in your choice of hues. “As the colors change, you glance and know if the pollen count in the air is higher than usual.” Why not a jacket that hugs the wearer every time she receives a “like” on her Facebook page? (This, from one of David’s students.) Or a toothbrush that knows it is being used (and being used properly), and recognizes your good work, rewarding you with a discount at the dentist? (Oy. The gamification of dentistry! Nah, not in David’s hands. He’s smarter than that—check this out.) One of his entrepreneurial firms was hired by a big pharmaceutical firm to bring some life to the little plastic pill containers. Hoping to change the behavior of the the many patients who do not take our prescribed meds, David’s company, Vitality, changed the cap. The cap glows when you’re supposed to take a pill. Even better, the GlowCap texts you when you’ve forgotten to take a pill, and automatically sends refill messages your local pharmacy. The “adherence rate” is up to 94 percent, far better than the 71 percent achieved by a standard (boring, non-glowing, non-internet connected) vial. It’s information at a glance, again non-disruptive.

Why not a jacket that hugs the wearer every time she receives a “like” on her Facebook page? (This, from one of David’s students.) Or a toothbrush that knows it is being used (and being used properly), and recognizes your good work, rewarding you with a discount at the dentist? (Oy. The gamification of dentistry! Nah, not in David’s hands. He’s smarter than that—check this out.) One of his entrepreneurial firms was hired by a big pharmaceutical firm to bring some life to the little plastic pill containers. Hoping to change the behavior of the the many patients who do not take our prescribed meds, David’s company, Vitality, changed the cap. The cap glows when you’re supposed to take a pill. Even better, the GlowCap texts you when you’ve forgotten to take a pill, and automatically sends refill messages your local pharmacy. The “adherence rate” is up to 94 percent, far better than the 71 percent achieved by a standard (boring, non-glowing, non-internet connected) vial. It’s information at a glance, again non-disruptive. David’s vision of the future: whatever the device may do, it must be affordable, indestructible, easily used, and, when it makes sense, wearable. Lovable, too—his clever illustration of interactive medicine packaging are based upon faces that transform themselves. They’re happy when you’re doing the right thing, grumpy if you’re not.

David’s vision of the future: whatever the device may do, it must be affordable, indestructible, easily used, and, when it makes sense, wearable. Lovable, too—his clever illustration of interactive medicine packaging are based upon faces that transform themselves. They’re happy when you’re doing the right thing, grumpy if you’re not. David dreams of on-demand objects, and objects that learn and respond to personal needs. Vending machines, for example, that customize their offerings based upon “a prediction of what the person will like.” He envisions “digital shadows” for objects—information associated with physical objects enhanced by digital projection.

David dreams of on-demand objects, and objects that learn and respond to personal needs. Vending machines, for example, that customize their offerings based upon “a prediction of what the person will like.” He envisions “digital shadows” for objects—information associated with physical objects enhanced by digital projection. Geri Allen is one of those extraordinary jazz musicians whose influence runs wide and deep, but somehow, has not become as well-known as it ought to be. She’s a pianist with a resume that begins with a serious educational foundation: a master’s degree in ethnomusicology that has served her well (easy for me to see this because I’m approaching her life’s work some 35 years into a very good story). Her professional work begins with Mary Wilson and the Supremes in the early 1980s, and Brooklyn’s

Geri Allen is one of those extraordinary jazz musicians whose influence runs wide and deep, but somehow, has not become as well-known as it ought to be. She’s a pianist with a resume that begins with a serious educational foundation: a master’s degree in ethnomusicology that has served her well (easy for me to see this because I’m approaching her life’s work some 35 years into a very good story). Her professional work begins with Mary Wilson and the Supremes in the early 1980s, and Brooklyn’s  The awards began to roll in. Allen was in and out of the remaining avant-garde, which sounds much less radical now than in 1996 when she recorded “Hidden Man” with Ornette Coleman’s Sound Museum. In fact, by 1999, she was sounding very comfortable in a commercial setting, recording her popular CD, The Gathering, with Wallace Roney on flugelhorn and trumpet, Robin Eubanks on trombone, Buster Williams on bass, and Lenny White on drums, and others whose names are well-known from mainstream jazz records. A 2010 record, “Flying Toward the Sound,” made it to the top of many critic’s best-of-the-year lists.

The awards began to roll in. Allen was in and out of the remaining avant-garde, which sounds much less radical now than in 1996 when she recorded “Hidden Man” with Ornette Coleman’s Sound Museum. In fact, by 1999, she was sounding very comfortable in a commercial setting, recording her popular CD, The Gathering, with Wallace Roney on flugelhorn and trumpet, Robin Eubanks on trombone, Buster Williams on bass, and Lenny White on drums, and others whose names are well-known from mainstream jazz records. A 2010 record, “Flying Toward the Sound,” made it to the top of many critic’s best-of-the-year lists.

Geri Allen has been one of those artists that I’ve wanted to know more about. Now that I’ve written this article, now that I’ve done some concentrated listening, I’m realizing that I am just beginning to understand what she’s all about. The latest album is elegant and wonderful, soulful and reflective, sophisticated and consistently interesting, but my collection is now woefully incomplete. I have listened to the two predecessors in the trilogy, but I want them for my very own. The same is true for the work she did with Paul Motian and Charlie Haden, and for the work she did in 2010 with her group, Timeline.

Geri Allen has been one of those artists that I’ve wanted to know more about. Now that I’ve written this article, now that I’ve done some concentrated listening, I’m realizing that I am just beginning to understand what she’s all about. The latest album is elegant and wonderful, soulful and reflective, sophisticated and consistently interesting, but my collection is now woefully incomplete. I have listened to the two predecessors in the trilogy, but I want them for my very own. The same is true for the work she did with Paul Motian and Charlie Haden, and for the work she did in 2010 with her group, Timeline.

The next character in what turned out to a fascinating Saturday night at the Glimmerglass Festival just north of Cooperstown NY is Tobias Picker. If you don’t know the name, you should. “An American Tragedy” is his fourth opera (and one of several he has written with Gene Scheer’s libretto—you may know

The next character in what turned out to a fascinating Saturday night at the Glimmerglass Festival just north of Cooperstown NY is Tobias Picker. If you don’t know the name, you should. “An American Tragedy” is his fourth opera (and one of several he has written with Gene Scheer’s libretto—you may know

On Tuesdays and Wednesdays, Bob Mankoff rejects most everything he sees. He works as the cartoon editor at the New Yorker, a magazine whose sense of cartoon humor is famous, but extraordinarily difficult to define. This is not a new problem. In fact, the New Yorker has always suffered from a rough case of not being able to explain itself (the problem goes back to the 1920s when Writer’s Digest asked the New Yorker’s editors to advise writers interested in the magazine; in essence, the New Yorker editors could not).

On Tuesdays and Wednesdays, Bob Mankoff rejects most everything he sees. He works as the cartoon editor at the New Yorker, a magazine whose sense of cartoon humor is famous, but extraordinarily difficult to define. This is not a new problem. In fact, the New Yorker has always suffered from a rough case of not being able to explain itself (the problem goes back to the 1920s when Writer’s Digest asked the New Yorker’s editors to advise writers interested in the magazine; in essence, the New Yorker editors could not). “How About Never – Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons” is a kind of small-scale coffee table biography, half text and half cartoons. As with the New Yorker magazine, it’s difficult not to be attracted to the cartoons, but I was good: I read the whole book including all of Mankoff’s confessional text and all of his chosen cartoons. What surprised me: only a few of the cartoons made me smile or laugh. And that got me to thinking about how difficult it must be, to select from the stack of 500 cartoons from regular contributors and an equal number from wannabes. Mankoff writes, “eventually, I cull the pile down to fifty or so, which I’ll take to the Wednesday afternoon cartoon meeting…” where the stack will be winnowed down to just seventeen, maybe eighteen cartoons that will be published in the magazine. (There are, and have always been, so many rejects, Mankoff started a new venture called Cartoon Bank to give exposure to the rejects—and earn some money for himself [before he joined the magazine as cartoon editor] and for other working cartoonists.

“How About Never – Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons” is a kind of small-scale coffee table biography, half text and half cartoons. As with the New Yorker magazine, it’s difficult not to be attracted to the cartoons, but I was good: I read the whole book including all of Mankoff’s confessional text and all of his chosen cartoons. What surprised me: only a few of the cartoons made me smile or laugh. And that got me to thinking about how difficult it must be, to select from the stack of 500 cartoons from regular contributors and an equal number from wannabes. Mankoff writes, “eventually, I cull the pile down to fifty or so, which I’ll take to the Wednesday afternoon cartoon meeting…” where the stack will be winnowed down to just seventeen, maybe eighteen cartoons that will be published in the magazine. (There are, and have always been, so many rejects, Mankoff started a new venture called Cartoon Bank to give exposure to the rejects—and earn some money for himself [before he joined the magazine as cartoon editor] and for other working cartoonists.