Perhaps it was just a whimsical idea that takes shape on vacation, when the mind is free, the ocean breeze is blowing, and a violin shop appears out of nowhere. Or maybe I really will learn to play the violin. Without any musical experience or proper knowledge, I wandered into the shop and asked a few silly questions about buying a proper violin and learning to play. The shopkeeper, who also fixes violins and other stringed instruments in a workshop above the store, was patient with me, and suggested that I read a book to learn more. He recommended a book. I bought it, read it, and found myself not much smarter than before. I put the thought of a violin aside, then focused on where we might eat dinner that night.

Perhaps it was just a whimsical idea that takes shape on vacation, when the mind is free, the ocean breeze is blowing, and a violin shop appears out of nowhere. Or maybe I really will learn to play the violin. Without any musical experience or proper knowledge, I wandered into the shop and asked a few silly questions about buying a proper violin and learning to play. The shopkeeper, who also fixes violins and other stringed instruments in a workshop above the store, was patient with me, and suggested that I read a book to learn more. He recommended a book. I bought it, read it, and found myself not much smarter than before. I put the thought of a violin aside, then focused on where we might eat dinner that night.

Exhausted from far too much driving, we completed the next day’s drive with a visit to a favorite bookstore. And there, nearly forgotten on a bottom shelf, was hardcover book with an illustration of a violin on the cover. It was not a how-to-play or how-to-buy book, but some sort of story that combined music, science, and biography. It was late, I was toting a basketful of books, and tossed American Luthier onto the pile. (And recalled that a luthier made guitars, but I was not so sure they also made violins. They do.) The subtitle was appealing: “The Art & Science of the Violin”–this was more the book I had in mind. The author is Quincy Whitney, formerly of the Boston Globe. The subject of the book: the extraordinary work of Carleen Hutchins, an extraordinary scientist and craftsperson who did nothing less than reinvent the violin (and, along the way, a family of eight violin-like instruments, including one of the coolest upright string basses the world has ever known).

From the start, it’s clear that Ms. Hutchins is an extraordinary human being. She begins as a most curious child, then a teen who can build all sorts of things, then finds her way first into science as the kind of teacher who keeps a menagerie and a small farm in her classroom, then meets the right person at the right time and begins to play the viola, then decides she’ll build one. (Her whole life is like that.)

Well, the violins we know, the ones that are played by nearly all classical violinists and nearly all contemporary fiddlers, are all based upon designs developed in the 1550s by Andrea Amati. Two generations later, grandson Niccolo Amati continued the family tradition, but lost his kin in the plague. He taught two apprentices whose work continues to define the contemporary design of violins. Both are revered: Guarneri and, of course, Stradivari. When the latter died in 1727, the art, science and craftsmanship associated with Cremona violin-making was nearly lost, but two hundred years later, a new violin-making school was begun, apparently initiated in a fit of nationalism by Benito Mussolini in 1937. Stradivari made over a thousand violins, and half of them survive.

For hundreds of years, the violin has been a standard instrument for classical musicians, and, of course, for chamber groups, chamber orchestras and symphony orchestras. The past is revered, the classic instruments are revered, and the tradition is revered. But Carleen Hutchins asked the obvious question: was it possible to improve upon a design that was five hundred years old? Working initially as a craftsperson–always in her kitchen (her home in Montclair, NJ was always her workshop)–she developed a deep understanding of the science of acoustics and surrounded herself with friends who played in chamber groups. She learned to solve problems by testing (her basement was elaborately soundproofed to allow for extremely careful measurement in the wee hours when traffic and other sounds in her suburban neighborhood were least obtrusive), then by tinkering, making the tiniest adjustments by reshaping the fine contours of the plates, sound post, and other component parts. What began with an improved viola became a family of eight violins, each one sensibly placed within a range that would be familiar as soprano, alto, tenor, contrabass, etc. What began as a personal curiosity found itself on the cover of Scientific American magazine (1962, 1981), and also, the cover of the New Yorker (1989).

A violin is not invented or perfected in a moment. It must be played, enjoyed, improved, adjusted, and sometimes, rebuilt, often over years, decades or centuries. In fact, many high quality violins are antiques that been rebuilt and rebuilt so often that little of their original material remains. Still, this is the way the culture has evolved. And that culture is not especially welcoming to an inventor with a better mousetrap. That’s why so many of Hutchins’ instruments ended up in musical instrument museums, and so few have been heard on stage in performance. Happily, there is the Hutchins Consort, and they perform on Dr. Hutchins’ instruments. You can also watch some video, however limited, including part of a documentary in progress called Second Fiddle.

A violin is not invented or perfected in a moment. It must be played, enjoyed, improved, adjusted, and sometimes, rebuilt, often over years, decades or centuries. In fact, many high quality violins are antiques that been rebuilt and rebuilt so often that little of their original material remains. Still, this is the way the culture has evolved. And that culture is not especially welcoming to an inventor with a better mousetrap. That’s why so many of Hutchins’ instruments ended up in musical instrument museums, and so few have been heard on stage in performance. Happily, there is the Hutchins Consort, and they perform on Dr. Hutchins’ instruments. You can also watch some video, however limited, including part of a documentary in progress called Second Fiddle.

For the moment, my interest in the art and science of violin is sated. Author Quincy Whitney did a terrific job in telling a complicated story about art, science, music, social trends–I devoured the book in less than 36 hours. Will my path lead to learning the violin? For the moment, I’m curious but undecided, but much smarter than I was on Saturday afternoon before the book found me.

For the moment, my interest in the art and science of violin is sated. Author Quincy Whitney did a terrific job in telling a complicated story about art, science, music, social trends–I devoured the book in less than 36 hours. Will my path lead to learning the violin? For the moment, I’m curious but undecided, but much smarter than I was on Saturday afternoon before the book found me.

I started by creating as much open desk space as possible. IKEA to the rescue: a pair of white Limmnon 79-inch long, 23 inch deep desktops, each costing $45. One for each long wall, plus an ALEX 9-drawer white cabinet for storage, and a variety of old storage cubes recaptured from the basement and from other rooms. So far, I have not found the perfect roll-around task chair–a future project. The bookcases remained in place–the white Billy shelf units that are both inexpensive and look great.

I started by creating as much open desk space as possible. IKEA to the rescue: a pair of white Limmnon 79-inch long, 23 inch deep desktops, each costing $45. One for each long wall, plus an ALEX 9-drawer white cabinet for storage, and a variety of old storage cubes recaptured from the basement and from other rooms. So far, I have not found the perfect roll-around task chair–a future project. The bookcases remained in place–the white Billy shelf units that are both inexpensive and look great.

The flood lights were wonderful for work at the easel, but far too bright for every day room lighting, and totally useless for watercolor and drawing at the desk, I researched task lights–somewhat unfamiliar to me–and found a very cool company called

The flood lights were wonderful for work at the easel, but far too bright for every day room lighting, and totally useless for watercolor and drawing at the desk, I researched task lights–somewhat unfamiliar to me–and found a very cool company called  The new

The new

What else? Plenty of time to organize too many art supplies. The need for pleasant music (mission accomplished thanks to some forgotten stereo equipment in the basement). And–big discovery, however obvious it may seem–once a painting is complete, it needs to live somewhere. When I kept all of the finished work in a box flat box, this was not a problem. Now, I felt the need to display recent work, if for no reason except my own assessments. Once again, IKEA provided a solution: 45-inch long Mosslandia “picture ledges” (just reduced: now just $9.99– and I hope they’re not being discontinued).

What else? Plenty of time to organize too many art supplies. The need for pleasant music (mission accomplished thanks to some forgotten stereo equipment in the basement). And–big discovery, however obvious it may seem–once a painting is complete, it needs to live somewhere. When I kept all of the finished work in a box flat box, this was not a problem. Now, I felt the need to display recent work, if for no reason except my own assessments. Once again, IKEA provided a solution: 45-inch long Mosslandia “picture ledges” (just reduced: now just $9.99– and I hope they’re not being discontinued).

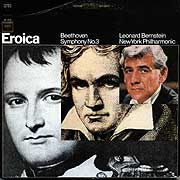

We started with one of the past century’s best–Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1961-2 for Deutsche Grammophon. I had just picked up a $4 LP, in very good shape, from

We started with one of the past century’s best–Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1961-2 for Deutsche Grammophon. I had just picked up a $4 LP, in very good shape, from  Next up: Leonard Bernstein from the same. Era. This was my LP, purchased decades ago, kept in it boxed set, played maybe ten times. This was a master work from Columbia Records at the label’s prime. The performance is ambitious, engaging, flowing–but the sound of the horns and the strings was compressed, very limited in highs and lows. We wanted to hear the depths of Beethoven explored by Bernstein in his prime–but the recording let us down.

Next up: Leonard Bernstein from the same. Era. This was my LP, purchased decades ago, kept in it boxed set, played maybe ten times. This was a master work from Columbia Records at the label’s prime. The performance is ambitious, engaging, flowing–but the sound of the horns and the strings was compressed, very limited in highs and lows. We wanted to hear the depths of Beethoven explored by Bernstein in his prime–but the recording let us down. Before going modern, we decided to go for Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, first on LP and then on CD, recorded in 1949–before stereo recording was available. This was state-of-the-art at the time, but the dynamic range was so limited on these recordings, they did not stand up to modern listening. Historical interest only.

Before going modern, we decided to go for Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, first on LP and then on CD, recorded in 1949–before stereo recording was available. This was state-of-the-art at the time, but the dynamic range was so limited on these recordings, they did not stand up to modern listening. Historical interest only. I had high hopes for my treasured 1995 CD set from Colin Davis and the Staastkapelle Dresden. Sure enough the CD really delivered–a full range of highs, lows and everything in-between. Wonderful placement of instruments. Lots of clarity, distinct individual violins and basses, just the right horn sounds. I was excited–but somehow, the listening experience was a few marks less than thrilling. After Karajan and Bernstein, the passion felt a little lacking. A fine performance is not the same as a thrilling performance, and when I’m listening to Beethoven’s Eroica, I want to be thrilled. But the sound was more satisfying here than it was on any of the LPs.

I had high hopes for my treasured 1995 CD set from Colin Davis and the Staastkapelle Dresden. Sure enough the CD really delivered–a full range of highs, lows and everything in-between. Wonderful placement of instruments. Lots of clarity, distinct individual violins and basses, just the right horn sounds. I was excited–but somehow, the listening experience was a few marks less than thrilling. After Karajan and Bernstein, the passion felt a little lacking. A fine performance is not the same as a thrilling performance, and when I’m listening to Beethoven’s Eroica, I want to be thrilled. But the sound was more satisfying here than it was on any of the LPs. Now here’s my last one. It’s a digital remaster from 1963, a CD box that I didn’t even know I owned. It’s the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig led by

Now here’s my last one. It’s a digital remaster from 1963, a CD box that I didn’t even know I owned. It’s the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig led by

The youthful exuberance is gone, the social awareness is increasing, the production is slicker by 1969’s “Stand” — “you’ve been sitting much too long—there’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong!” – “there’s a midget standing tall, and a giant beside him about to fall!” It feels a bit dated, a golden oldie, a solid memory but the controlled chaos and the crazy audio production is a thing of the past. From the same album (called Stand), there’s “Sing a Simple Song” and “Everyday People”— probably the group’s high water mark— and both of those songs bind the no-holds-barred past with the glossier, socially consciousness future. The same album’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (same lyric, “Don’t call me whitey, nigger”) is a sincere push toward revolution.

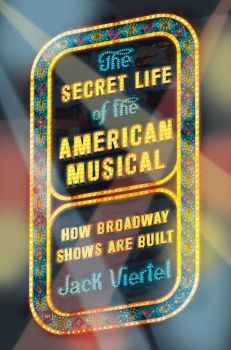

The youthful exuberance is gone, the social awareness is increasing, the production is slicker by 1969’s “Stand” — “you’ve been sitting much too long—there’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong!” – “there’s a midget standing tall, and a giant beside him about to fall!” It feels a bit dated, a golden oldie, a solid memory but the controlled chaos and the crazy audio production is a thing of the past. From the same album (called Stand), there’s “Sing a Simple Song” and “Everyday People”— probably the group’s high water mark— and both of those songs bind the no-holds-barred past with the glossier, socially consciousness future. The same album’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (same lyric, “Don’t call me whitey, nigger”) is a sincere push toward revolution. Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this: Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern. Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

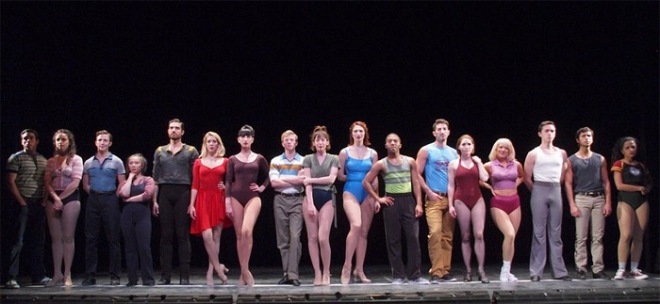

The turnaround story begins, as it ought to begin, with a pitch from a creative professional to a producer. The two remarkable people in this particular scene are Public Theater producer Joseph Papp and choreographer-director Michael Bennett. Reidel: “Bennett arrived at Papp’s office at the Public Theater carrying a bulky Sony reel-to-reel recorder and several reels of tape. He had nearly twenty-four hours of interviews with Broadway dancers. He thought there might be a show somewhere in those hours and hours of tape. He played some of them for Papp. After to listening to the recordings for forty-five minutes, Papp said, ‘OK, let’s do it.”

The turnaround story begins, as it ought to begin, with a pitch from a creative professional to a producer. The two remarkable people in this particular scene are Public Theater producer Joseph Papp and choreographer-director Michael Bennett. Reidel: “Bennett arrived at Papp’s office at the Public Theater carrying a bulky Sony reel-to-reel recorder and several reels of tape. He had nearly twenty-four hours of interviews with Broadway dancers. He thought there might be a show somewhere in those hours and hours of tape. He played some of them for Papp. After to listening to the recordings for forty-five minutes, Papp said, ‘OK, let’s do it.”