“Not every show has an ‘I Want’ song. Or a conditional love song, or a main event, or even an 11 o’clock number. But most do.”

The terminology may be unfamiliar, but the ideas are not.

A Broadway-style musical begins with an Overture, except when it doesn’t. Is the overture the lightning bolt that energizes the whole enterprise? Or is a divine spirit that visits a particular script, score, director, performer, ensemble, or theater?

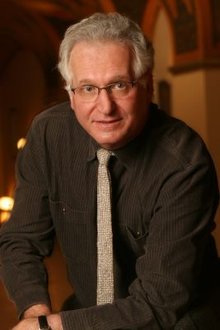

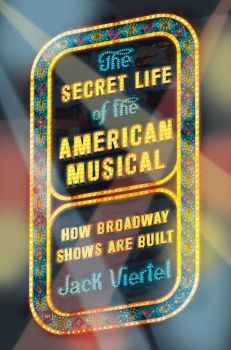

Form matters. That’s the mantra of Jack Viertel who wrote a book with the odd title, The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows are Built. He’s the Artistic Director of Encores!, responsible for the simple re-staging of three musicals every year for Broadway-literate audiences. During the recent past, Encores! has produced and presented “1776,” Do I Hear a Waltz, Cabin in the Sky, Zorba!, Paint Your Wagon, Lady Be Good!, Fiorello!, Lost in the Stars and Where’s Charley—mostly shows from the 1940s, 50s, 60s, 70s. As for more recent shows, Viertel questions their meanderings away from proper form and structure.

He is a man who has helped to construct magic—his credits include Hairspray, Angels in America and After Midnight—so his opinions are both well-formed and well-informed. He has credibility. I learned a lot by reading his book, in part for professional purposes, but mostly because he’s an terrific teacher with a subject that fascinates me.

In his words: “How do you begin a show?” How does a musical greet the audience at the door? How do creative artists introduce the characters, set the tone, communicate point of view, create a sense of style, a milieu? Do you begin with the story, the subject, the community in which the story is set, the main characters?”

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

Pantaloons and tunics,

Courtesans and eunuchs,

Funerals and chases,

Baritones and basses,

Panderers,

Philanderers,

Cupidity,

Timidity…

You get the idea. (Go listen to the song! It’s terrific.)

Another show provides the textbook example of Broadway construction. The opening scene in Gypsy is a mirror image of the closing conceit—and both are built around the song, “Let Me Entertain You!” (Sondheim wrote those lyrics, too!)

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

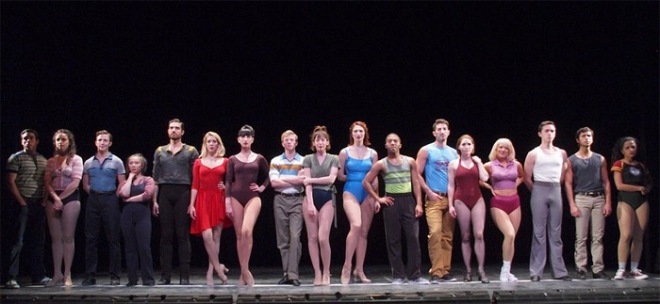

Some shows combine the traditional role of the opening number with the inevitable song that follows, called the “I Want” song. “Good Morning Baltimore!” provides a taste of what Tracy wants in Hairspray, but A Chorus Line is more direct in its use of I Want in its opening number:

God I hope I get it.

I hope I get it.

How many people does he need…

I really need this job.

Please, God, I need this job.

I’ve got to get this job!”

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

The conditional love song comes next—or follows shortly after. “If I Loved You” from Carousel, ”I’ve imagined every bit of him / From his strong moral fiber / To the wisdom in his head / To the homely aroma of his pipe..” sets up the unlikely romance between a gambler and a Salvation Army worker in Guys and Dolls.And now, things become complicated. (Heck, you could write a book about it…) There is “The Noise” — “a pure expression expression of energy” that’s intended to be, mostly, fun, without much consideration for story. Try, for example, “Put on Your Sunday Clothes” from Hello, Dolly. Then, the plot thickens, a secondary romance is introduced, unexpected obstacles, confusion that must be resolved within the next hour or so. The disappointment—a character has made an unfortunate choice. Tentpoles lead to expanded audience expectations: “I had a dream / a dream about you, Baby! / It’s gonna come true, Baby! / They think that we’re through, but, Baby…” From at least one character’s point of view, “Everything’s Coming Up Roses” but others in Gypsy have their doubts—and when the first act curtain falls, many of the characters are gone, never to be seen again.

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

Buy the book. See the musical(s). If you’re in NYC, buy a ticket to “Encores!” — even if you don’t know the show, will not be disappointed because now you’ve taken a glimpse backstage, under the hood, inside the dream. It’s all a glorious confection—characters in the midst of the most dramatic adventure of their lives stopping everything to sing their hearts out and dane a lot. Makes no logical sense. But it’s wonderful. And it’s been going on for the better part of a century. And there are people who are very, very good at this particular art form. Every once in a while, it’s nice to celebrate them.