“Not every show has an ‘I Want’ song. Or a conditional love song, or a main event, or even an 11 o’clock number. But most do.”

The terminology may be unfamiliar, but the ideas are not.

A Broadway-style musical begins with an Overture, except when it doesn’t. Is the overture the lightning bolt that energizes the whole enterprise? Or is a divine spirit that visits a particular script, score, director, performer, ensemble, or theater?

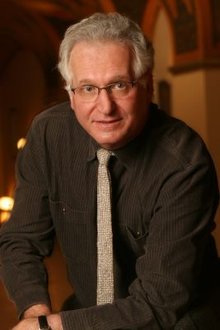

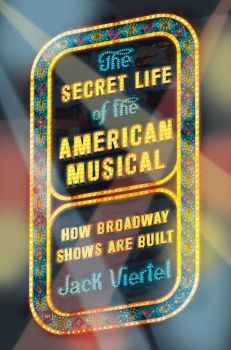

Form matters. That’s the mantra of Jack Viertel who wrote a book with the odd title, The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows are Built. He’s the Artistic Director of Encores!, responsible for the simple re-staging of three musicals every year for Broadway-literate audiences. During the recent past, Encores! has produced and presented “1776,” Do I Hear a Waltz, Cabin in the Sky, Zorba!, Paint Your Wagon, Lady Be Good!, Fiorello!, Lost in the Stars and Where’s Charley—mostly shows from the 1940s, 50s, 60s, 70s. As for more recent shows, Viertel questions their meanderings away from proper form and structure.

He is a man who has helped to construct magic—his credits include Hairspray, Angels in America and After Midnight—so his opinions are both well-formed and well-informed. He has credibility. I learned a lot by reading his book, in part for professional purposes, but mostly because he’s an terrific teacher with a subject that fascinates me.

In his words: “How do you begin a show?” How does a musical greet the audience at the door? How do creative artists introduce the characters, set the tone, communicate point of view, create a sense of style, a milieu? Do you begin with the story, the subject, the community in which the story is set, the main characters?”

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

Pantaloons and tunics,

Courtesans and eunuchs,

Funerals and chases,

Baritones and basses,

Panderers,

Philanderers,

Cupidity,

Timidity…

You get the idea. (Go listen to the song! It’s terrific.)

Another show provides the textbook example of Broadway construction. The opening scene in Gypsy is a mirror image of the closing conceit—and both are built around the song, “Let Me Entertain You!” (Sondheim wrote those lyrics, too!)

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

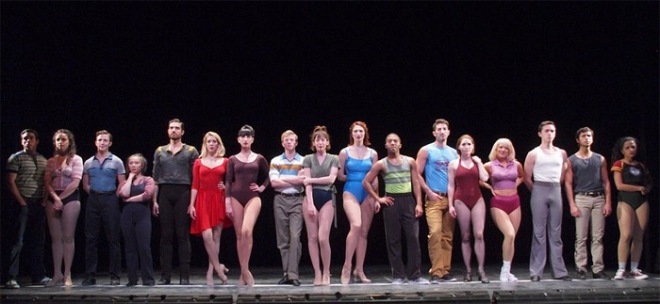

Some shows combine the traditional role of the opening number with the inevitable song that follows, called the “I Want” song. “Good Morning Baltimore!” provides a taste of what Tracy wants in Hairspray, but A Chorus Line is more direct in its use of I Want in its opening number:

God I hope I get it.

I hope I get it.

How many people does he need…

I really need this job.

Please, God, I need this job.

I’ve got to get this job!”

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

The conditional love song comes next—or follows shortly after. “If I Loved You” from Carousel, ”I’ve imagined every bit of him / From his strong moral fiber / To the wisdom in his head / To the homely aroma of his pipe..” sets up the unlikely romance between a gambler and a Salvation Army worker in Guys and Dolls.And now, things become complicated. (Heck, you could write a book about it…) There is “The Noise” — “a pure expression expression of energy” that’s intended to be, mostly, fun, without much consideration for story. Try, for example, “Put on Your Sunday Clothes” from Hello, Dolly. Then, the plot thickens, a secondary romance is introduced, unexpected obstacles, confusion that must be resolved within the next hour or so. The disappointment—a character has made an unfortunate choice. Tentpoles lead to expanded audience expectations: “I had a dream / a dream about you, Baby! / It’s gonna come true, Baby! / They think that we’re through, but, Baby…” From at least one character’s point of view, “Everything’s Coming Up Roses” but others in Gypsy have their doubts—and when the first act curtain falls, many of the characters are gone, never to be seen again.

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

Buy the book. See the musical(s). If you’re in NYC, buy a ticket to “Encores!” — even if you don’t know the show, will not be disappointed because now you’ve taken a glimpse backstage, under the hood, inside the dream. It’s all a glorious confection—characters in the midst of the most dramatic adventure of their lives stopping everything to sing their hearts out and dane a lot. Makes no logical sense. But it’s wonderful. And it’s been going on for the better part of a century. And there are people who are very, very good at this particular art form. Every once in a while, it’s nice to celebrate them.

d the corner from the museum is The Four Way Restaurant, where Stax musicians, producers and engineers used to eat, and where I shared a table with a preacher who was touring the South, speaking about how Wal-Mart was destroying the local economy. Fried chicken, fried fish, side dishes of greens and yams. Preacher told me he would be heading next to Clarksdale, then on to Cleveland (Mississippi) and Indianola, just a few hours south. Next morning, I decided to skip a few speeches at a trade show and head for Clarksdale, figuring I’d be back just after lunch. I guess I didn’t anticipate driving down Highway 61, or waiting on Aunt Sarah to do her daily deliveries before serving lunch in what turned out to be one of the few places to buy lunch in the once-vibrant small city of Clarksdale. And if it wasn’t for my visit with Roger Stolle in the

d the corner from the museum is The Four Way Restaurant, where Stax musicians, producers and engineers used to eat, and where I shared a table with a preacher who was touring the South, speaking about how Wal-Mart was destroying the local economy. Fried chicken, fried fish, side dishes of greens and yams. Preacher told me he would be heading next to Clarksdale, then on to Cleveland (Mississippi) and Indianola, just a few hours south. Next morning, I decided to skip a few speeches at a trade show and head for Clarksdale, figuring I’d be back just after lunch. I guess I didn’t anticipate driving down Highway 61, or waiting on Aunt Sarah to do her daily deliveries before serving lunch in what turned out to be one of the few places to buy lunch in the once-vibrant small city of Clarksdale. And if it wasn’t for my visit with Roger Stolle in the

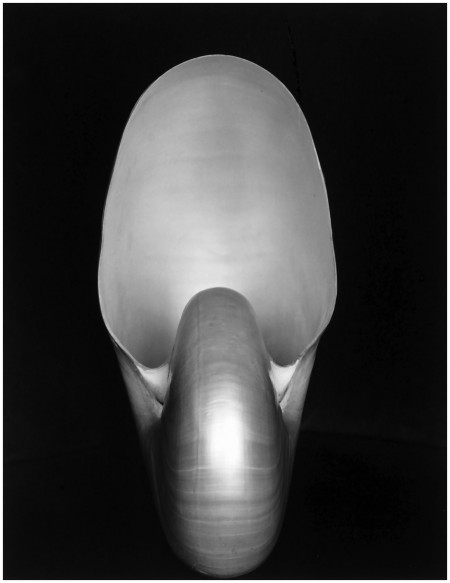

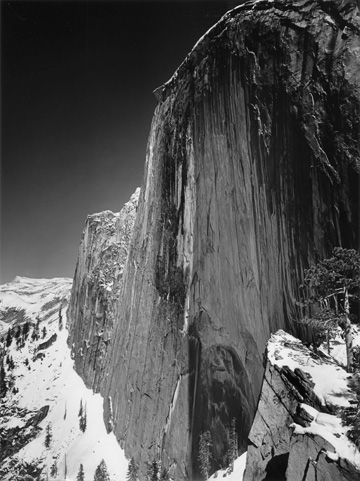

When the photographers in Group f.64 started out, they found themselves in what, today, seems to be an unlikely situation. Photographers on the east coast followed a mostly European tradition anchored in painting. On the West Coast, the fad was pictorialism in which photographs were not considered viable unless they were altered to look like other forms of art. For example, the pictorial photographers often hand-colored their work, used soft focus lenses, and created faux brushstrokes during the photographic development process. Pictorialism found some rather odd expressions: one very popular West Coast photographer named William Mortensen was, according to Alinder, “the very vocal champion of the Pictorialists. He applied his expertise in set design and the latest in Hollywood makeup artistry: elaborately costumed historical portraits and tableaux. He staged each picture’s setting, building a fictional alternative universe, often of a teasing salaciousness or portraying scenes of horror, his models transformed into monsters with heavy makeup.” Mortensen was among America’s most famous photographers and easily photography’s most prolific teacher. In a series of well-described articles in Camera Craft magazine, he sparred with Ansel Adams who took the position of photography as pure art form that required none of the nonsense that Mortensen promoted.

When the photographers in Group f.64 started out, they found themselves in what, today, seems to be an unlikely situation. Photographers on the east coast followed a mostly European tradition anchored in painting. On the West Coast, the fad was pictorialism in which photographs were not considered viable unless they were altered to look like other forms of art. For example, the pictorial photographers often hand-colored their work, used soft focus lenses, and created faux brushstrokes during the photographic development process. Pictorialism found some rather odd expressions: one very popular West Coast photographer named William Mortensen was, according to Alinder, “the very vocal champion of the Pictorialists. He applied his expertise in set design and the latest in Hollywood makeup artistry: elaborately costumed historical portraits and tableaux. He staged each picture’s setting, building a fictional alternative universe, often of a teasing salaciousness or portraying scenes of horror, his models transformed into monsters with heavy makeup.” Mortensen was among America’s most famous photographers and easily photography’s most prolific teacher. In a series of well-described articles in Camera Craft magazine, he sparred with Ansel Adams who took the position of photography as pure art form that required none of the nonsense that Mortensen promoted.

Moving from the old world of traditional broadcast networks through hybrid innovators including cable networks then into the new world of internet services and alternative funding models, she covers the waterfront. There are interviews with knowledgable leaders from Netflix, Kickstarter, HBO, and other companies whose work matters a great deal in 2015.

Moving from the old world of traditional broadcast networks through hybrid innovators including cable networks then into the new world of internet services and alternative funding models, she covers the waterfront. There are interviews with knowledgable leaders from Netflix, Kickstarter, HBO, and other companies whose work matters a great deal in 2015. Nowadays, most cable networks are coming to the same conclusion: their future is going to be defined by original programming (scripted and unscripted, both have their place), and by events (which tend to work only sometimes, in part because they’re expensive and also because they’re difficult to construct with any frequency). So there’s the conundrum for the deeper future: as each cable network, and each subscription service, develops and markets their own unique programs, the audience becomes that much more fragmented. The pie slices become smaller, the ability for any individual player to make an impact becomes that much more challenging.

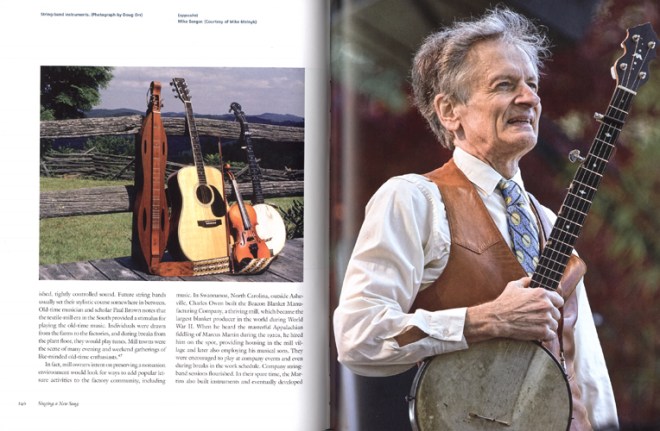

Nowadays, most cable networks are coming to the same conclusion: their future is going to be defined by original programming (scripted and unscripted, both have their place), and by events (which tend to work only sometimes, in part because they’re expensive and also because they’re difficult to construct with any frequency). So there’s the conundrum for the deeper future: as each cable network, and each subscription service, develops and markets their own unique programs, the audience becomes that much more fragmented. The pie slices become smaller, the ability for any individual player to make an impact becomes that much more challenging. Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

In book, lecture and conversation, Scott McCloud has taught me a lot. But it’s one thing to be a teacher and another to be the creator of the material. The expectations become unreasonably high. The student wants to see every lesson incorporated in exquisite elegant prose and picture. The story must be perfect. The storytelling, better than perfect.

In book, lecture and conversation, Scott McCloud has taught me a lot. But it’s one thing to be a teacher and another to be the creator of the material. The expectations become unreasonably high. The student wants to see every lesson incorporated in exquisite elegant prose and picture. The story must be perfect. The storytelling, better than perfect. As David tells his story, the evidence of Scott’s visual storytelling skill propels the sense of reality. There are extreme close-ups and wide streetscapes, frames without dialog that communicate more than those with words, and an interesting isolation technique in which David is fully inked against a world that is rendered only in sketch form. There’s a girl, of course, an angel of sorts, and as in the second act of Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, a difficult-to-fathom big city art scene (Scott and Stephen wrestle with some similar themes.) Main character David tells us that he hates parties and by extension, the whole scene, but those pages are among Scott’s very finest: a crowded multi-page sequence where you can feel the energy of a noisy large-scale party and the frustration in coping with the idiots who won’t leave you alone while you’re trying to keep some girl within your visual range, while you’re trying to chase her before she’s gone forever. (Gee, he does this well!)

As David tells his story, the evidence of Scott’s visual storytelling skill propels the sense of reality. There are extreme close-ups and wide streetscapes, frames without dialog that communicate more than those with words, and an interesting isolation technique in which David is fully inked against a world that is rendered only in sketch form. There’s a girl, of course, an angel of sorts, and as in the second act of Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, a difficult-to-fathom big city art scene (Scott and Stephen wrestle with some similar themes.) Main character David tells us that he hates parties and by extension, the whole scene, but those pages are among Scott’s very finest: a crowded multi-page sequence where you can feel the energy of a noisy large-scale party and the frustration in coping with the idiots who won’t leave you alone while you’re trying to keep some girl within your visual range, while you’re trying to chase her before she’s gone forever. (Gee, he does this well!) For me, that’s the treat, same as reading Understanding Comics, same as watching Scott lecture, same as spending time with him. We’re living in a world filled with stories and ideas, and clever ways of communicating. If it’s all as simple as A-B-C, then the magic isn’t so magical. Life’s more complicated than a straight series of logical events—and that’s the beauty of a well0-crafted graphic novel. No shopping mall cinema audiences to satisfy with a clearly articulated happy ending. No need for extreme helicopter crashes or uncomfortable explosions punctuated with graphic violence. The story can be personal, it can be told by a single storyteller (provided the storyteller is willing and able to spend several years writing and drawing his epic), and it can be somewhat nonlinear. With that, a reader’s note: do it in one day. That is, find yourself a good stormy day, turn off the cell phone, and just lose yourself. Don’t think too much—just allow the storyteller control your mind for a few hours. We do this for movies all the time—with this book, you don’t want to disengage. You want to pay attention, and grab the ideas as they’re unfolding, then return to study the craft. Last weekend, I read the book. Today, a Saturday, I returned to study the construction of the visual sequences, the use of characters, my favorite scenes and how they were put together.

For me, that’s the treat, same as reading Understanding Comics, same as watching Scott lecture, same as spending time with him. We’re living in a world filled with stories and ideas, and clever ways of communicating. If it’s all as simple as A-B-C, then the magic isn’t so magical. Life’s more complicated than a straight series of logical events—and that’s the beauty of a well0-crafted graphic novel. No shopping mall cinema audiences to satisfy with a clearly articulated happy ending. No need for extreme helicopter crashes or uncomfortable explosions punctuated with graphic violence. The story can be personal, it can be told by a single storyteller (provided the storyteller is willing and able to spend several years writing and drawing his epic), and it can be somewhat nonlinear. With that, a reader’s note: do it in one day. That is, find yourself a good stormy day, turn off the cell phone, and just lose yourself. Don’t think too much—just allow the storyteller control your mind for a few hours. We do this for movies all the time—with this book, you don’t want to disengage. You want to pay attention, and grab the ideas as they’re unfolding, then return to study the craft. Last weekend, I read the book. Today, a Saturday, I returned to study the construction of the visual sequences, the use of characters, my favorite scenes and how they were put together.

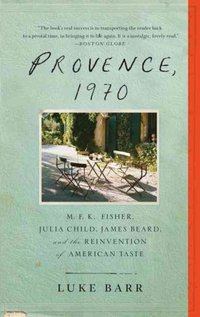

Their story is told by Ms. Fisher’s nephew, Luke Barr in a book that’s becoming quite popular. It’s called Provence, 1970, and it provided a winter weekend’s entertainment. There are menus, and they lead into wonderful stories of friends building meals together– serious cooks experimenting and showing off for their foodie friends. It’s loose and informal, and I kept fantasizing about what it might have been like to join them, if just for a night. Few nonfiction books draw me into the story in quite this way, and it was fun to be a part of it, if only as an observer nearly fifty years later.

Their story is told by Ms. Fisher’s nephew, Luke Barr in a book that’s becoming quite popular. It’s called Provence, 1970, and it provided a winter weekend’s entertainment. There are menus, and they lead into wonderful stories of friends building meals together– serious cooks experimenting and showing off for their foodie friends. It’s loose and informal, and I kept fantasizing about what it might have been like to join them, if just for a night. Few nonfiction books draw me into the story in quite this way, and it was fun to be a part of it, if only as an observer nearly fifty years later. P.S.: I think I need to read more by M.F.K. Fisher. One intriguing title is a 1942 book called “How to Cook a Wolf.” I found a

P.S.: I think I need to read more by M.F.K. Fisher. One intriguing title is a 1942 book called “How to Cook a Wolf.” I found a