When I write “classical music,” you probably think Bach, Mozart or Beethoven, or maybe Chopin, Brahms, or Tchaikovsky. Bach died in 1750, Mozart in 1791, Beethoven in 1827, Chopin in 1849, Brahms in 1893, and Tchaikovsky in 1897. If you think in more modern terms, there’s Igor Stravinsky (d. 1971), and two musical buddies, Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein (both d. 1990). Will we ever see another famous classical composer? Or is all of this old news, overtaken by the expense of orchestras, the greying (whiting?) of the audience, the popularity of crossover music or orchestras playing Star Wars in concert, or the popularity of song-based (as opposed to album-based) streaming services?

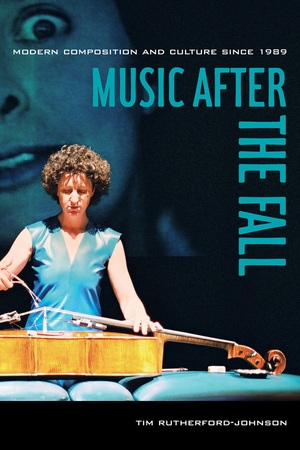

Yes. But. Classical music has been dying for centuries. If you’re seeking the new Beethoven, you’re on the wrong path. If you’re wondering how new ideas and new technologies have energized and blurred the definition of classical music, I’ve got a book for you. It was recommended by Alex Ross, whose own book, The Rest Is Noise, is probably the best book about 20th century music. Tim Rutherford-Johnson is a journalist, formerly the contemporary music editor at both Grove Music Online and The Oxford Dictionary of Music, so his background is solid.Tim begins After the Fall: Modern Composition and Culture Since 1989 before the breaking of the 21st century, and manages to place music in the micro-context of the times: this is a history book filled with very recent history, covering just short of thirty years.

Some of the contemporary composers’ names may be familiar. John Adams writes instrumental music and operas; you may be familiar with Shaker Loops, or Nixon in China. John Luther Adams has become quite famous for Become Ocean. (I am curious about his music, and will likely devote a full article to his work next year.) Thomas Adès is a British composer who has become quite popular. John Corigliano is both a popular conductor and a composer, perhaps best known for his post-2001 tribute, Of Rage and Remembrance. Philip Glass and Steve Reich pioneered a new approach to classical music in the second half of the 20th century. Reich’s experimentation with combinations of sounds and music influenced lots of 21st century musicians (his influence is so widespread, and so much a part of contemporary culture, many modern musicians don’t quite realize that their music ties back to his work). These legendary 20th century innovators are roughly the same age–an astonishing 81/82 years old.

Henryk Gòrecki passed in 2010, but his Symphony 3, recorded by David Zinman and the London Sinfonietta, with vocals by Dawn Upshaw, has been a tremendous commercial success. Its appeal overlaps the work of Arvo Pärt, also in his eighties, whose contemplative recordings with ECM New Series, and other labels, resulted in the Vice article, “How a 78-Year-Old Estonian Composer Became the Hottest Thing in Music.” This past weekend, The New York Times published a somewhat similar article about György Kurtág from Romania, who is now 92. He finally finished his first opera, based upon the Samuel Beckett play, Endgame.

Add John Tavener (d. 2013) to the list, too.

Obvious question: are all of the new classical composers dead, or in their 80s or 90s? Nah, they’re just the ones who have enjoyed the last gasps of the recorded compact disc format. And there isn’t an easy way to promote a streaming thing, so you’re going to need to look beyond records to learn about the next-gen classical music. Or read the good advice provided by Tim Rutherford-Johnson. For example…

Kronos photographed in San Francisco, CA March 26, 2013©Jay Blakesberg

There’s the Kronos Quartet, a popular group that has long experimented with modern classical compositions, often in combination with music from many different parts of the world. In 2015, they released One Earth, One People, One Love: Kronos Plays Terry Riley (another contemporary classical composer from the 20th century), but their catalog includes work with or by Franghiz Ali-Zadeh (Azerbaijan), Sigur Rós (Iceland), Osvaldo Golijov (Argentina), Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen (Denmark), Witold Lutoslawski (Poland), the familiar Henryk Gòrecki (Poland–they play on several of his most popular recordings), and also Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and Thelonius Monk.

There’s Mark Turnage, who wrote a provocative, but accessible, opera called Anna Nicole (Smith–a former Playboy model “equally notorious for her surgically enhanced body and her marriage to a a billionaire sixty-three years her senior”). According to Tim, Turnage is “a brash yet accessible talent.” It debuted at London’s Covent Garden with Led Zepellin’s John Paul Jones in the band.

We are just beginning Tim’s tour. As music becomes less place-based, in part due to technology and in part due to a desire to perform in new ways, he considers The Silk Road Ensemble’s concerts which “blend Western and non-Western, art and vernacular” as the musicians play traditional (native) and nontraditional instruments– it is “built on the principles of cultural exchange, learning and understanding… more like a jazz group than an orchestra).

Messing with the expected is central to new ways of thinking about music. For example,, “(Brian) Ferneyhough’s more recent music disrupts the pathways of memory, overloading, thwarting, or redirecting them. Incipits [1996], for violin and small ensemble, for example, is composed of several separate “beginnings,” which draw the listener into a set of expectations they must keep having to drop and reboot [a musical parallel to Italo Calvino’s novel, If one a winter’s night a traveler). Memory here is activated, only to wiped clean.”

I found the two sections about “Loss” and “Recovery” especially interesting. Loss introduces the work of John Luther Adams in connection with “evocations of the landscape, the English and Latin names of birds and plants, poems in two Native American languages…Adams has sought to render aspects of the Alaskan wildness, drawing attention to specific places and their need for protection.” (The work is a “quasi-opera” called Earth and the Great Weather.) In Recovery, he describes the work of Azerbaijani composer Franghiz Ali-Zadeh which “identifies a space between past and present, traditional and contemporary, and Asian and Western…Because it exists in gaps–deliberately not fixed to anything, the music of Ali-Zadeh, Kanchelli, and other composers of the former Soviet Union proved able to slip between stylistic boundaries…”

Of course, I could go on, but my curiosity is now well ahead of my listening experience. I need to catch up, to slide away from emails and websites so I can spend more time attending to the music that is being made all around me. This is made somewhat more complicated by my current (and growing) interest in music that precedes Bach, Beethoven and the rest–as I begin an exploration of a remarkable early music group from England called The Sixteen, whose CDs should arrive any day now.

As I look forward, I also look back. Inevitably, I stumble into strong connections between the present, the future and the deep past. That’s what I love about music discovery.

And it is endless.

The fun begins in York about 10,000 years ago. The Romans showed up about 2,000 years ago–certainly by 71 AD–and you can walk the

The fun begins in York about 10,000 years ago. The Romans showed up about 2,000 years ago–certainly by 71 AD–and you can walk the  After the Vikings, York weathered a less distinguished period. One of the worst episodes: the burning of Jews supposedly under government protection in the 1100s–an old castle is still on the site. By 1300, York was both an important government and trading center for England, and remained so until the 1500s. You can walk the streets and see medieval buildings–not unlike walking the world of Harry Potter (celebrated by several souvenir shops).

After the Vikings, York weathered a less distinguished period. One of the worst episodes: the burning of Jews supposedly under government protection in the 1100s–an old castle is still on the site. By 1300, York was both an important government and trading center for England, and remained so until the 1500s. You can walk the streets and see medieval buildings–not unlike walking the world of Harry Potter (celebrated by several souvenir shops).

What have I missed? The quiet pub where the World Cup semi-final victory for England was celebrated in a most dignified manner. The streets outside where everyone’s cheeks (probably both kinds) were painted with tiny English soccer flags, where people sang, loudly with with tremendous dancing exuberance, about how the Cup was “coming home.” Nearly every pub in town was pounding with energy and music–including, inexplicably, “Take Me Home Country Roads” and other boisterous (?) John Denver tunes to which every Brit seemed to know every word; the medley ended with the British (?) classic, “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” All great fun!

What have I missed? The quiet pub where the World Cup semi-final victory for England was celebrated in a most dignified manner. The streets outside where everyone’s cheeks (probably both kinds) were painted with tiny English soccer flags, where people sang, loudly with with tremendous dancing exuberance, about how the Cup was “coming home.” Nearly every pub in town was pounding with energy and music–including, inexplicably, “Take Me Home Country Roads” and other boisterous (?) John Denver tunes to which every Brit seemed to know every word; the medley ended with the British (?) classic, “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” All great fun!

For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain,

For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain,

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

A violin is not invented or perfected in a moment. It must be played, enjoyed, improved, adjusted, and sometimes, rebuilt, often over years, decades or centuries. In fact, many high quality violins are antiques that been rebuilt and rebuilt so often that little of their original material remains. Still, this is the way the culture has evolved. And that culture is not especially welcoming to an inventor with a better mousetrap. That’s why so many of Hutchins’ instruments ended up in musical instrument museums, and so few have been heard on stage in performance. Happily, there is the

A violin is not invented or perfected in a moment. It must be played, enjoyed, improved, adjusted, and sometimes, rebuilt, often over years, decades or centuries. In fact, many high quality violins are antiques that been rebuilt and rebuilt so often that little of their original material remains. Still, this is the way the culture has evolved. And that culture is not especially welcoming to an inventor with a better mousetrap. That’s why so many of Hutchins’ instruments ended up in musical instrument museums, and so few have been heard on stage in performance. Happily, there is the

l, I wondered whether a greater investment would significantly improve the experience of listening to records. As I wondered, I found myself spending $20-30 in record shops specializing in vinyl—not buying the new pristine artisan pressings that seem to cost $25-40, but used copies that cost a tenth as much (so $30 bucks buys 8-10 LPs in surprisingly good condition).

l, I wondered whether a greater investment would significantly improve the experience of listening to records. As I wondered, I found myself spending $20-30 in record shops specializing in vinyl—not buying the new pristine artisan pressings that seem to cost $25-40, but used copies that cost a tenth as much (so $30 bucks buys 8-10 LPs in surprisingly good condition).

Of course, listening in a well-appointed professional listening room is not much like listening at home. I decided to give the VPI Prime a try. We added the Dynavector DV-20X2L that sounded so good on the Rotel turntable, and connected it to the Sutherland Insight pre-amp, also a wonderful friend for the Rotel. And off we go with a DG recording of Emil Gilels performing Brahms’s first piano concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic—with its bombastic opening, now so clearly rendered with absolute distinction between the instruments, and minimal (if any) congestion in the extreme sequences with what sounds like tons of instruments all blasting their hearts out. Shift to the quieter string and wind sequences, and everything is sweet, present, energetic, really wonderful.

Of course, listening in a well-appointed professional listening room is not much like listening at home. I decided to give the VPI Prime a try. We added the Dynavector DV-20X2L that sounded so good on the Rotel turntable, and connected it to the Sutherland Insight pre-amp, also a wonderful friend for the Rotel. And off we go with a DG recording of Emil Gilels performing Brahms’s first piano concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic—with its bombastic opening, now so clearly rendered with absolute distinction between the instruments, and minimal (if any) congestion in the extreme sequences with what sounds like tons of instruments all blasting their hearts out. Shift to the quieter string and wind sequences, and everything is sweet, present, energetic, really wonderful. And yet, none of that matters. Not when Emil Gilels is playing the piano, and I’m litening to a turntable, a cartridge and a phono stage that were, five months ago, a completely theoretical idea. Now, the sound feels so natural, so effortless, so entirely pleasant, so exhilarating, that I wonder why I waited so long to improve the “analog front end” of an otherwise terrific stereo system.

And yet, none of that matters. Not when Emil Gilels is playing the piano, and I’m litening to a turntable, a cartridge and a phono stage that were, five months ago, a completely theoretical idea. Now, the sound feels so natural, so effortless, so entirely pleasant, so exhilarating, that I wonder why I waited so long to improve the “analog front end” of an otherwise terrific stereo system.

Before we move on to specific types of equipment, consider this: the tiny stylus is likely to pick up not only the sound from the grooves in the record (and the inevitable scratches, clicks and pops), but also the sound of the turntable’s motor, the resonance of the tonearm, and any other sounds in the room, including conversations, dog barks, and other disturbances. For cartridge, tone arm, and turnable manufacturers, playing the design game requires tremendous attention to mitigation and near-elimination of vibration, resonance, and other unwanted sounds. At the same time, a properly-designed cartridge must make the very best of the available (physical) information inside the grooves of every record. Fortunately, every record is made in accordance with very precise manufacturing standards (in the U.S.,

Before we move on to specific types of equipment, consider this: the tiny stylus is likely to pick up not only the sound from the grooves in the record (and the inevitable scratches, clicks and pops), but also the sound of the turntable’s motor, the resonance of the tonearm, and any other sounds in the room, including conversations, dog barks, and other disturbances. For cartridge, tone arm, and turnable manufacturers, playing the design game requires tremendous attention to mitigation and near-elimination of vibration, resonance, and other unwanted sounds. At the same time, a properly-designed cartridge must make the very best of the available (physical) information inside the grooves of every record. Fortunately, every record is made in accordance with very precise manufacturing standards (in the U.S.,  Fortunately, there are a fair number of audiophiles who listen to all sorts of equipment, and share their opinions. Chad Stelly, who works at

Fortunately, there are a fair number of audiophiles who listen to all sorts of equipment, and share their opinions. Chad Stelly, who works at

So l started listening. Or, first, I paid a local audio dealer to mount to cartridge properly—this is not an easy thing to do properly—and then I started listening to the DV20x20 on my Rotel RB900 turntable. I started with a favorite orchestral performance that I’ve written about

So l started listening. Or, first, I paid a local audio dealer to mount to cartridge properly—this is not an easy thing to do properly—and then I started listening to the DV20x20 on my Rotel RB900 turntable. I started with a favorite orchestral performance that I’ve written about  When I’m listening to a new piece of equipment—something I don’t do very often, to be honest, because I make my decisions with such care—one subjective test is how often I swap records. If I find myself sitting and listening, often to a whole side of an LP, I know that I’ve found a winner. So now I’m spending hours listening, and rediscovering discs that I know pretty well—and finding new joy because there is more detail, punch, clarity, and sense of being there with so many LPs. I’m very impressed by the Dynavector DV20x20, and I’ll attempt to close out with the reasons why. On classical recordings, I find the overall presence most appealing, closely followed by the punch and sweep of the more exciting passages, and increased refinement of solo violins, female voice, clarinets, oboes, and flutes. On jazz recordings, it’s undoubtedly the crispness of the drum kit—so precise, with just the right sense of attack and decay—though I do love what happens when I listen to Oscar Peterson playing piano, and I know that because I now find it difficult to listen to him as background music. I pay more attention to the music! On rock LPs, it’s the bass and the percussion that gets me, but also the higher tinkering on an electric or pedal steel guitar. When I listen to a singer, I hear nuances that I’m not sure I heard, or paid attention to, before. In short, this tiny component—a phono cartridge half the size of my pinky—is providing a whole lot of enjoyment.

When I’m listening to a new piece of equipment—something I don’t do very often, to be honest, because I make my decisions with such care—one subjective test is how often I swap records. If I find myself sitting and listening, often to a whole side of an LP, I know that I’ve found a winner. So now I’m spending hours listening, and rediscovering discs that I know pretty well—and finding new joy because there is more detail, punch, clarity, and sense of being there with so many LPs. I’m very impressed by the Dynavector DV20x20, and I’ll attempt to close out with the reasons why. On classical recordings, I find the overall presence most appealing, closely followed by the punch and sweep of the more exciting passages, and increased refinement of solo violins, female voice, clarinets, oboes, and flutes. On jazz recordings, it’s undoubtedly the crispness of the drum kit—so precise, with just the right sense of attack and decay—though I do love what happens when I listen to Oscar Peterson playing piano, and I know that because I now find it difficult to listen to him as background music. I pay more attention to the music! On rock LPs, it’s the bass and the percussion that gets me, but also the higher tinkering on an electric or pedal steel guitar. When I listen to a singer, I hear nuances that I’m not sure I heard, or paid attention to, before. In short, this tiny component—a phono cartridge half the size of my pinky—is providing a whole lot of enjoyment.

Fine adjustments matter a lot. When I was first setting up my reference stereo system, I moved each speaker perhaps 1/8 of an inch toward or away from one another, and I routinely heard meaningful changes in the female vocalist’s

Fine adjustments matter a lot. When I was first setting up my reference stereo system, I moved each speaker perhaps 1/8 of an inch toward or away from one another, and I routinely heard meaningful changes in the female vocalist’s