Or, more or less, the Wikipedia of 1493, the year Columbus first visited the Western Hemisphere.

It’s a big, old book, the kind of illustrated, illuminated, hand-lettered book that I would never expected to see in my own home. But here it is, nearly 2 inches thick, reproduced by the always-intrepid Taschen publishing company. As you can see, it’s quite a beautiful old book, with colorful illustrations of kings and townscapes on every page. Looking carefully, I can make out a page about Florencia, also known as Florenz, today’s Florence, Italy, and on another page, the now-German town of Wurtzburg. There’s Rom, or Roma, with its bridges and towers, and the formidable city gates. Here’s a stylist family tree, but the old lettering is difficult for me to understand. A book like this might occupy a few minutes in a museum, and then, I’d move on. But to have it in my hands, well, that’s another thing. Its age demands respect, and time to study, not to peruse but to study, every page, slowly and with a sense of insight and discovery.

It’s a big, old book, the kind of illustrated, illuminated, hand-lettered book that I would never expected to see in my own home. But here it is, nearly 2 inches thick, reproduced by the always-intrepid Taschen publishing company. As you can see, it’s quite a beautiful old book, with colorful illustrations of kings and townscapes on every page. Looking carefully, I can make out a page about Florencia, also known as Florenz, today’s Florence, Italy, and on another page, the now-German town of Wurtzburg. There’s Rom, or Roma, with its bridges and towers, and the formidable city gates. Here’s a stylist family tree, but the old lettering is difficult for me to understand. A book like this might occupy a few minutes in a museum, and then, I’d move on. But to have it in my hands, well, that’s another thing. Its age demands respect, and time to study, not to peruse but to study, every page, slowly and with a sense of insight and discovery.

Fortunately, the cardboard slipcase includes not only the main volume, but a large-format color paperback book entitled The Book of Chronicles. In essence, it’s a guidebook, written in English, nicely illustrated, and it helps to make sense of the larger volume. It begins,

Fortunately, the cardboard slipcase includes not only the main volume, but a large-format color paperback book entitled The Book of Chronicles. In essence, it’s a guidebook, written in English, nicely illustrated, and it helps to make sense of the larger volume. It begins,

The handwritten layout for Hartmann Schedel’s Weltchronik, or Chronicle of the World, widely known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, has survived in the municipal library of Nuremberg… This chronicle is structured as follows: the First Age from Creation to the Deluge; the Second Age from the Deluge to the Birth of Abraham; the Third Age from the Birth of Abraham to the Kingdom of David; the Fourth Age from the beginning of the Kingdom of David to the Babylonian Captivity; the Sixth (and longest) Age from the Birth of Christ to the present day. A brief Seventh Age follows, reporting from the coming of the Antichrist at the end of the world and predicting the Last Judgement. This is followed, somewhat unsystematically, by descriptions of various towns…digressions on the subject of natural catastrophes, wars, reports on the founding of cities…biblical stories.”

The work was put together at the pleasure of several benefactors, financial backers who are credited. (Their names and stories are explained in the paperback, but none will be familiar to contemporary readers.) One familiar name is the artist Albrecht Dürer, whose sketches may have been the basis for the many woodcuts found in the Chronicle.

Approximately 2,000 copies were published, and about half went unsold. Many of the copies were sold by booksellers–nice to know that there were booksellers around 1500, sad to think that there may be none within our lifetimes. Books were sold sold by banking and trading houses, and their clients. Academics also sold books as a means to earn some extra money. Many books were sold in and near Nuremberg, but they were also sold in Milan, Florence, Geneva, Venice, Lyon, and Paris. The majority of the books were published in Latin, but some were published in German. It surprises me that we know so much about the publishing and marketing of a book that was current more than 500 years ago.

Here’s the scoop on Constantinople, circa 1493:

Here’s a look at Rome, slightly improved through digital technology:

Here’s what you’re seeing: “On the left we can see the huge Coliseum. To its right are the ruins of the Theater of Marcellus and Santa Maria Rotunda, formerly the Pantheon, the best-preserved of all Rome’s ancient buildings (27 BC), rededicated under Pope Bonafacio IV (AD 609) to Mary and all the martyrs. In the foreground, we see the Aurelian Wall with various city gates. From left to right, they are Porto Quirinale, the Porta Pinciana, and the Porta del Popolo, which was the first church visited by pilgrims arriving from the north and Germany. Just behind it is the bridge of St. Angelo which leads across the Tiber to the Castellum S. Angeli. From there, the pilgrim can continue straight ahead to the Vatican or left to the (old) St. Peter’s. At the top of the picture, in the middle of the Vatican walls and to the far right of the papal residence, is the Villa del Belvedere, built under Pope Innocent VIII (1484-1492).

Page after page, I kept wondering how I might touch the page and magically transform the old Latin or German text into words I could read. Odd to be wondering why a half-millenium old book won’t behave like an iPad, but that’s the way we’re now thinking about the world. Perhaps that’s progress.

Birthday: August 4, 1961

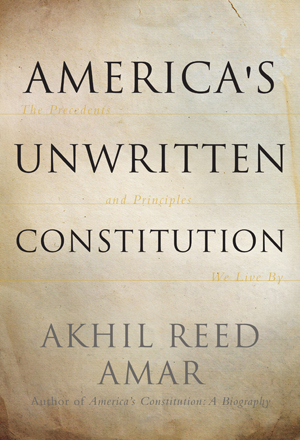

Birthday: August 4, 1961 I started reading Amar’s book,

I started reading Amar’s book,

Yeah, well, my list isn’t very long, either. Easy enough to list Mao, Chang Kai-Shek, Chao en-Lai, maybe the classical pianist Lang Lang, and the basketball player Yao Ming. Maybe Jet Li, who is probably from Hong Kong (I checked; he is from Hong Kong).

Yeah, well, my list isn’t very long, either. Easy enough to list Mao, Chang Kai-Shek, Chao en-Lai, maybe the classical pianist Lang Lang, and the basketball player Yao Ming. Maybe Jet Li, who is probably from Hong Kong (I checked; he is from Hong Kong). There are good stories about emperor Kublai Khan, and the beginning of Chinese drama as initiated by Guan Hanqing. You may know Zheng He, an admiral who led a large fleet to Africa and other far away places a few decades before Christopher Columbus was toilet-trained (I wonder whether there were toilets in Genoa in the 1450s?) Rumors about Zheng He discovering the American mainland are, apparently, quite wrong, the work of someone who mistranslated Chinese historical documents.

There are good stories about emperor Kublai Khan, and the beginning of Chinese drama as initiated by Guan Hanqing. You may know Zheng He, an admiral who led a large fleet to Africa and other far away places a few decades before Christopher Columbus was toilet-trained (I wonder whether there were toilets in Genoa in the 1450s?) Rumors about Zheng He discovering the American mainland are, apparently, quite wrong, the work of someone who mistranslated Chinese historical documents.

So that’s one migration. There’s another 13.5 million people moving during the period 1815-1915. Those people are moving, mostly, from Europe to America. Lots from Ireland, England, Scandinavia, and later, Spain, Italy, and eastern Europe–the peopling of America.

So that’s one migration. There’s another 13.5 million people moving during the period 1815-1915. Those people are moving, mostly, from Europe to America. Lots from Ireland, England, Scandinavia, and later, Spain, Italy, and eastern Europe–the peopling of America.

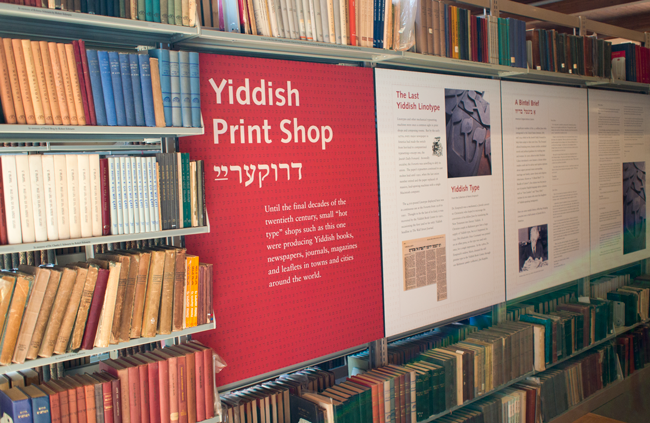

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.