Diffusion spectrum image shows brain wiring in a healthy human adult. The thread-like structures are nerve bundles, each containing hundreds of thousands of nerve fibers.

Source: Source: Van J. Wedeen, M.D., MGH/Harvard U. To learn more about the government’s new connectome project, click on the brain.

You may recall recent coverage of a major White House initiative: mapping the brain. In that statement, there is ambiguity. Do we mean the brain as a body part, or do we mean the brain as the place where the mind resides? Mapping the genome–the sequence of the four types of molecules (nucleotides) that compose your DNA–is so far along that it will soon be possible, for a very reasonable price, to purchase your personal genome pattern.

A connectome is, in the words of the brilliantly clear writer and MIT scientist, Sebastian Seung, is: “the totality of connections between the neurons in [your] nervous system.” Of course, “unlike your genome, which is fixed from the moment of conception, your connectome changes throughout your life. Neurons adjust…their connections (to one another) by strengthening or weakening them. Neurons reconnect by creating and eliminating synapses, and they rewire by growing and retracting branches. Finally, entirely new neurons are created and existing ones are eliminated, through regeneration.”

In other words, the key to who we are is not located in the genome, but instead, in the connections between our brain cells–and those connections are changing all the time.The brain, and, by extension, the mind, is dynamic, constantly evolving based upon both personal need and stimuli.

With his new book, the author proposes a new field of science for the study of the connectome, the ways in which the brain behaves, and the ways in which we might change the way it behaves in new ways. It isn’t every day that I read a book in which the author proposes a new field of scientific endeavor, and, to be honest, it isn’t every day that I read a book about anything that draws me back into reading even when my eyes (and mind) are too tired to continue. “Connectome” is one of those books that is so provocative, so inherently interesting, so well-written, that I’ve now recommended it to a great many people (and now, to you as well).

With his new book, the author proposes a new field of science for the study of the connectome, the ways in which the brain behaves, and the ways in which we might change the way it behaves in new ways. It isn’t every day that I read a book in which the author proposes a new field of scientific endeavor, and, to be honest, it isn’t every day that I read a book about anything that draws me back into reading even when my eyes (and mind) are too tired to continue. “Connectome” is one of those books that is so provocative, so inherently interesting, so well-written, that I’ve now recommended it to a great many people (and now, to you as well).

Seung is at his best when exploring the space between brain and mind, the overlap between how the brain works and how thinking is made possible. For example, he describes how the idea of Jennifer Aniston, a job that is done not by one neuron, but by a group of them, each recognizing a specific aspect of what makes Jennifer Jennifer. Blue eyes. Blonde hair. Angular chin. Add enough details and the descriptors point to one specific person. The neurons put the puzzle together and trigger a response in the brain (and the mind). What’s more, you need not see Jennifer Aniston. You need only think about her and the neurons respond. And the connection between these various neurons is strengthened, ready for the next Jennifer thought. The more you think about Jennifer Aniston, the more you think about Jennifer Aniston.

From here, it’s a reasonable jump to the question of memory. As Seung describes the process, it’s a matter of strong neural connections becoming even stronger through additional associations (Jennifer and Brad Pitt, for example), repetition (in all of those tabloids?), and ordering (memory is aided by placing, for example, the letters of the alphabet in order). No big revelations here–that’s how we all thought it worked–but Seung describes the ways in which scientists can now measure the relative power (the “spike”) of the strongest impulses. Much of this comes down to the image resolution finally available to long-suffering scientists who had the theories but not the tools necessary for confirmation or further exploration.

Next stop: learning. Here, Seung focuses on the random impulses first experienced by the neurons, and then, through a combination of repetition of patterns (for example), a bird song emerges. Not quickly, nor easily, but as a result of (in the case of the male zebra finches he describes in an elaborate example) of tens of thousands of attempts, the song emerges and can then be repeated because the neurons are, in essence, properly aligned. Human learning has its rote components, too, but our need for complexity is greater, and so, the connectome and its network of connections is far more sophisticated, and measured in far greater quantities, than those of a zebra finch. In both cases, the concept of a chain of neural responses is the key.

From here, the book becomes more appealing, perhaps, to fans of certain science fiction genres. Seung becomes fascinated with the implications of cryonics, or the freezing of a brain for later use. Here, he covers some of the territory familiar from Ray Kurzweil’s “How to Create a Mind” (recently, a topic of an article here). The topic of fascination: 0nce we understand the brain and its electrical patterns, is it possible to save those patterns of impulses in some digital device for subsequent sharing and/or retrieval? I found myself less taken with this theoretical exploration than the heart and soul of, well, the brain and mind that Seung explains so well. Still, this is what we’re all wondering: at what point does human brain power and computing brain power converge? And when they do, how much control will we (as opposed to, say Amazon or Google) exert over the future of what we think, what’s important enough to save, and what we hope to accomplish.

I just finished reading a book about the New Deal, that remarkable FDR-era transformation of America for the average American. Certainly, I knew and understood pieces and parts of the story, but there were so many factors, I needed a good writer (the author won a Pulitzer Prize) to put the whole thing into context for me. The author is Michael Hiltzik, and the book is called, simply, “

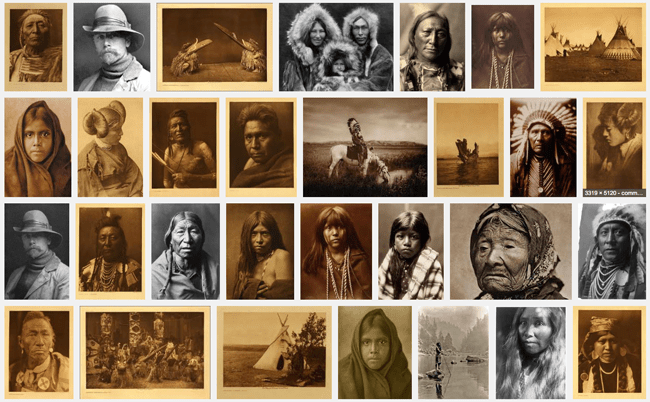

I just finished reading a book about the New Deal, that remarkable FDR-era transformation of America for the average American. Certainly, I knew and understood pieces and parts of the story, but there were so many factors, I needed a good writer (the author won a Pulitzer Prize) to put the whole thing into context for me. The author is Michael Hiltzik, and the book is called, simply, “ The woman in the photograph was a poor soul, without friends, the subject of ridicule among Seattle schoolchildren. She lived in a hovel. When the growing city of Seattle cleared its native population, she remained where she was, and the city grew up around her. Kick-is-om-lo was her name, but that was difficult to pronounce, so the local folk called her Princess Angeline. In 1896, Kick-is-om-lo was paid one dollar to pose for this picture–the equivalent of what she was able to earn in a whole week–by a struggling young photographer named Edward Curtis. To say this would be the first of many such images would be a substantial understatement.

The woman in the photograph was a poor soul, without friends, the subject of ridicule among Seattle schoolchildren. She lived in a hovel. When the growing city of Seattle cleared its native population, she remained where she was, and the city grew up around her. Kick-is-om-lo was her name, but that was difficult to pronounce, so the local folk called her Princess Angeline. In 1896, Kick-is-om-lo was paid one dollar to pose for this picture–the equivalent of what she was able to earn in a whole week–by a struggling young photographer named Edward Curtis. To say this would be the first of many such images would be a substantial understatement.

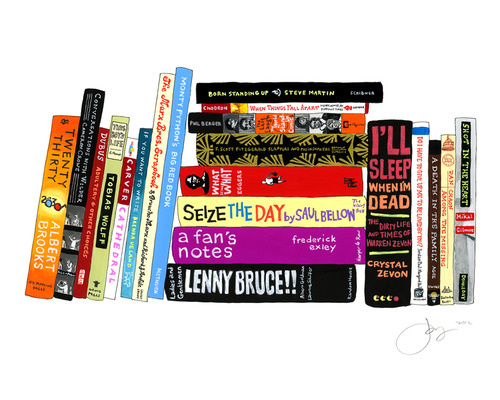

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh.

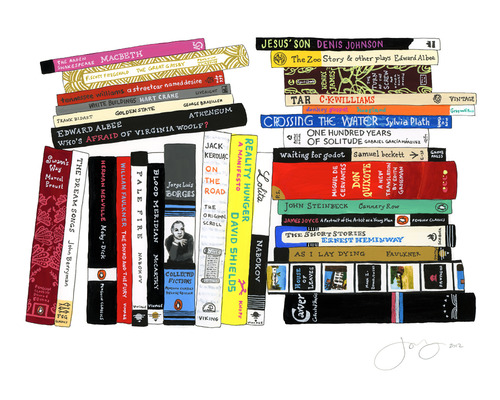

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh. James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.