You may not know the name Paul McGowan. If you’re interested in high-end audio, and/or you listen to a lot of recorded music, Paul is someone you ought to know. He’s the “P” in “PS Audio,” a leading maker of quality loudspeakers. He and his team have designed and built all sorts of audio products. And he’s been doing this for a half-century. That experience is now captured in a library of ten (!) volumes of a series called The Audiophile’s Guide. They’re available as a set (www.theaudiophilesguide.com) and as individual books. Each book is substantial — several hundred pages long, and costs about $40.

There are ten books. They cover, for example, The Stereo, The Loudspeaker, Analog Audio generally, Digital Audio generally, Vinyl, the all-important Listening Room, the Subwoofer, Headphones, Home Theater, and a distilled version of the series called The Collection.

The book about Vinyl is especially helpful. It begins at the beginning: the development and evolution of records, followed by a very clear explanation of “groove modulation” — the way record grooves interact with a phonograph stylus, which leads to a discussion of cutting masters, plating and pressing, and my favorite part, the debate about the quality of records vs. other recorded media. And so, the author eases into groove wall resistance, natural compression curves, and other particulars that make records sound so good — especially when the playback equipment is right.

The sound of vinyl is much affected by the operation of the turntable — the way the motor turns the circular table, for example — and the design of the tonearm. These concepts ride in the background of audiophile discussions, but here, author Paul McGowan shines — his articulate, direct, simple language makes the concepts compressible. The chapter called “Engineering Challenges of Tonearms” is not a lesson in technical engineering, but instead, a 2-page essay that pretty much tells the listener what they might want to know. Cartridges are also confusing and difficult to understand, but here, moving magnets, moving coils, cantilevers and other types of cartridge technology come to life, make sense, and provide the listening with a good basic understanding of what matters and why.

McGowan is equally good on the practice of buying just the right product for your individual purpose. And so: choosing a pre-amplifier, choosing a cartridge, and so on. There’s a turntable setup guide here, too, but I wish it included diagrams. If you’ve heard terms such as tracking force and azimuth, this book provides an easy way to learn the basics.

If you want to listen to music, but you feel as though you ought to know just enough about technology to advance your listening experience, this book series can be a very useful tool.

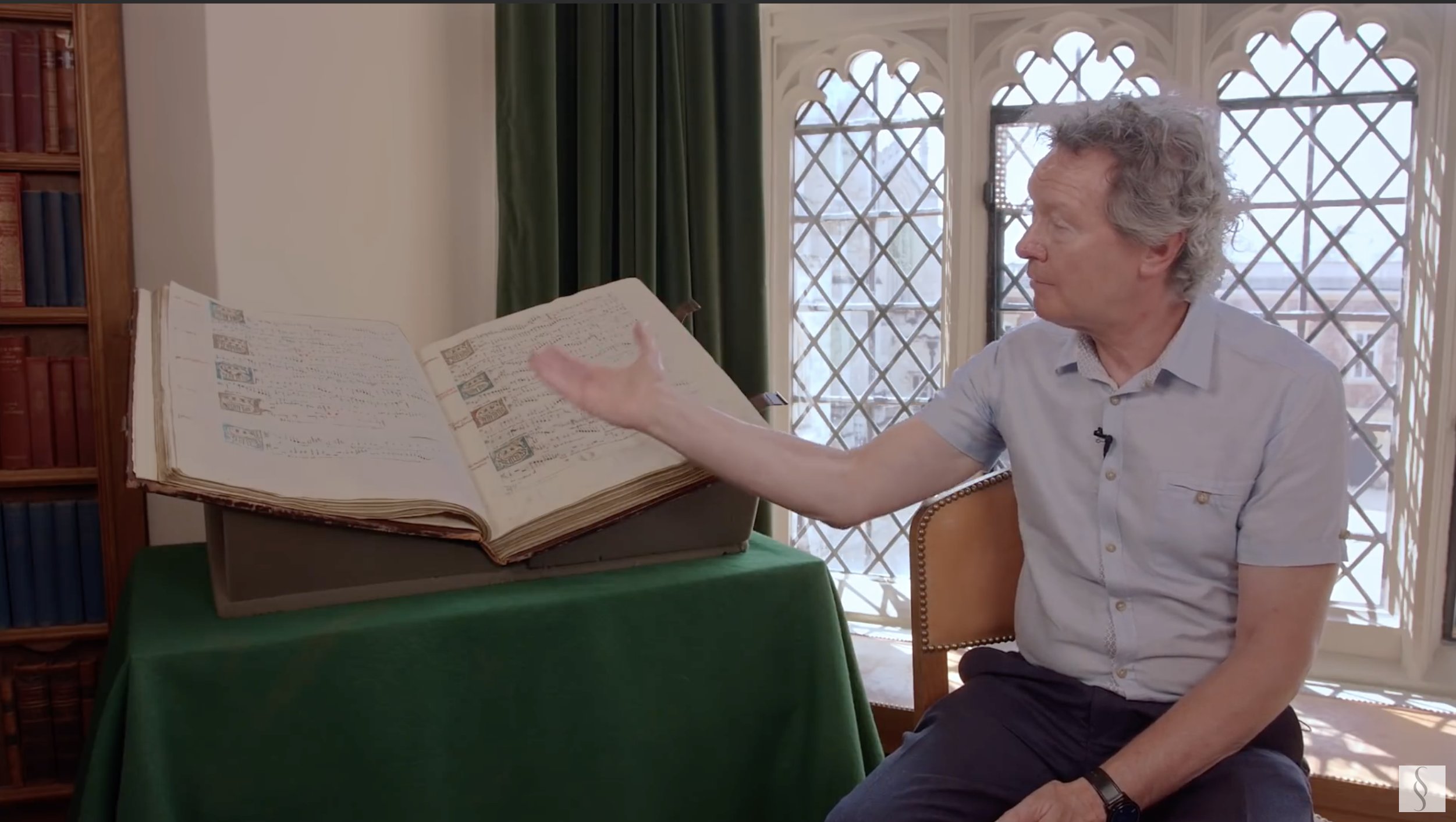

Spem in alium is the final entry in a

Spem in alium is the final entry in a  Renaissance Music. So much music, so little time–but then, much of this music has been performed for half a millennium. Regardless of my pace, it will survive. Today, in the hands and hearts of Harry Christophers, and his peers including John Eliot Gardiner, and others, it may be fair to say that it thrives as never before. The secret: these magical musicians are more than that. They are teachers. And I am their most willing student.

Renaissance Music. So much music, so little time–but then, much of this music has been performed for half a millennium. Regardless of my pace, it will survive. Today, in the hands and hearts of Harry Christophers, and his peers including John Eliot Gardiner, and others, it may be fair to say that it thrives as never before. The secret: these magical musicians are more than that. They are teachers. And I am their most willing student. For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain,

For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain,

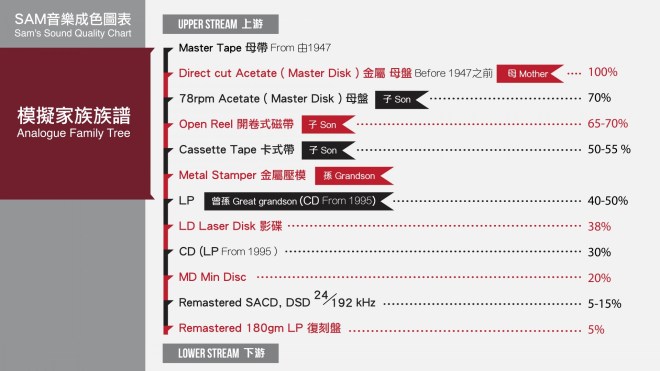

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

l, I wondered whether a greater investment would significantly improve the experience of listening to records. As I wondered, I found myself spending $20-30 in record shops specializing in vinyl—not buying the new pristine artisan pressings that seem to cost $25-40, but used copies that cost a tenth as much (so $30 bucks buys 8-10 LPs in surprisingly good condition).

l, I wondered whether a greater investment would significantly improve the experience of listening to records. As I wondered, I found myself spending $20-30 in record shops specializing in vinyl—not buying the new pristine artisan pressings that seem to cost $25-40, but used copies that cost a tenth as much (so $30 bucks buys 8-10 LPs in surprisingly good condition).

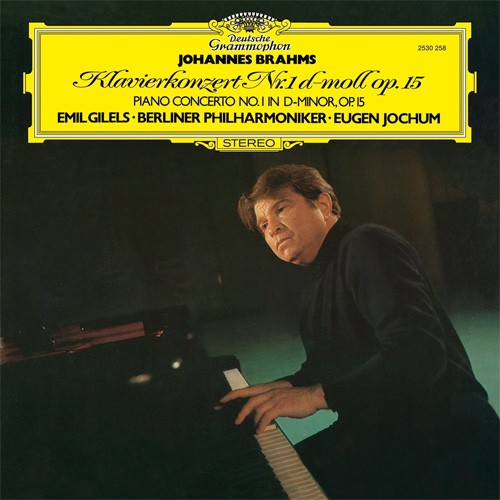

Of course, listening in a well-appointed professional listening room is not much like listening at home. I decided to give the VPI Prime a try. We added the Dynavector DV-20X2L that sounded so good on the Rotel turntable, and connected it to the Sutherland Insight pre-amp, also a wonderful friend for the Rotel. And off we go with a DG recording of Emil Gilels performing Brahms’s first piano concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic—with its bombastic opening, now so clearly rendered with absolute distinction between the instruments, and minimal (if any) congestion in the extreme sequences with what sounds like tons of instruments all blasting their hearts out. Shift to the quieter string and wind sequences, and everything is sweet, present, energetic, really wonderful.

Of course, listening in a well-appointed professional listening room is not much like listening at home. I decided to give the VPI Prime a try. We added the Dynavector DV-20X2L that sounded so good on the Rotel turntable, and connected it to the Sutherland Insight pre-amp, also a wonderful friend for the Rotel. And off we go with a DG recording of Emil Gilels performing Brahms’s first piano concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic—with its bombastic opening, now so clearly rendered with absolute distinction between the instruments, and minimal (if any) congestion in the extreme sequences with what sounds like tons of instruments all blasting their hearts out. Shift to the quieter string and wind sequences, and everything is sweet, present, energetic, really wonderful. And yet, none of that matters. Not when Emil Gilels is playing the piano, and I’m litening to a turntable, a cartridge and a phono stage that were, five months ago, a completely theoretical idea. Now, the sound feels so natural, so effortless, so entirely pleasant, so exhilarating, that I wonder why I waited so long to improve the “analog front end” of an otherwise terrific stereo system.

And yet, none of that matters. Not when Emil Gilels is playing the piano, and I’m litening to a turntable, a cartridge and a phono stage that were, five months ago, a completely theoretical idea. Now, the sound feels so natural, so effortless, so entirely pleasant, so exhilarating, that I wonder why I waited so long to improve the “analog front end” of an otherwise terrific stereo system.

Before we move on to specific types of equipment, consider this: the tiny stylus is likely to pick up not only the sound from the grooves in the record (and the inevitable scratches, clicks and pops), but also the sound of the turntable’s motor, the resonance of the tonearm, and any other sounds in the room, including conversations, dog barks, and other disturbances. For cartridge, tone arm, and turnable manufacturers, playing the design game requires tremendous attention to mitigation and near-elimination of vibration, resonance, and other unwanted sounds. At the same time, a properly-designed cartridge must make the very best of the available (physical) information inside the grooves of every record. Fortunately, every record is made in accordance with very precise manufacturing standards (in the U.S.,

Before we move on to specific types of equipment, consider this: the tiny stylus is likely to pick up not only the sound from the grooves in the record (and the inevitable scratches, clicks and pops), but also the sound of the turntable’s motor, the resonance of the tonearm, and any other sounds in the room, including conversations, dog barks, and other disturbances. For cartridge, tone arm, and turnable manufacturers, playing the design game requires tremendous attention to mitigation and near-elimination of vibration, resonance, and other unwanted sounds. At the same time, a properly-designed cartridge must make the very best of the available (physical) information inside the grooves of every record. Fortunately, every record is made in accordance with very precise manufacturing standards (in the U.S.,  Fortunately, there are a fair number of audiophiles who listen to all sorts of equipment, and share their opinions. Chad Stelly, who works at

Fortunately, there are a fair number of audiophiles who listen to all sorts of equipment, and share their opinions. Chad Stelly, who works at

So l started listening. Or, first, I paid a local audio dealer to mount to cartridge properly—this is not an easy thing to do properly—and then I started listening to the DV20x20 on my Rotel RB900 turntable. I started with a favorite orchestral performance that I’ve written about

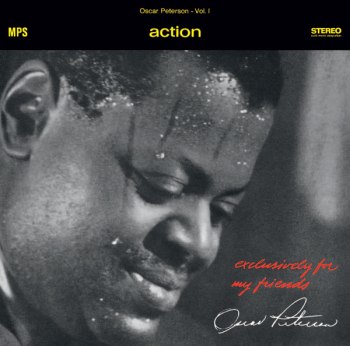

So l started listening. Or, first, I paid a local audio dealer to mount to cartridge properly—this is not an easy thing to do properly—and then I started listening to the DV20x20 on my Rotel RB900 turntable. I started with a favorite orchestral performance that I’ve written about  When I’m listening to a new piece of equipment—something I don’t do very often, to be honest, because I make my decisions with such care—one subjective test is how often I swap records. If I find myself sitting and listening, often to a whole side of an LP, I know that I’ve found a winner. So now I’m spending hours listening, and rediscovering discs that I know pretty well—and finding new joy because there is more detail, punch, clarity, and sense of being there with so many LPs. I’m very impressed by the Dynavector DV20x20, and I’ll attempt to close out with the reasons why. On classical recordings, I find the overall presence most appealing, closely followed by the punch and sweep of the more exciting passages, and increased refinement of solo violins, female voice, clarinets, oboes, and flutes. On jazz recordings, it’s undoubtedly the crispness of the drum kit—so precise, with just the right sense of attack and decay—though I do love what happens when I listen to Oscar Peterson playing piano, and I know that because I now find it difficult to listen to him as background music. I pay more attention to the music! On rock LPs, it’s the bass and the percussion that gets me, but also the higher tinkering on an electric or pedal steel guitar. When I listen to a singer, I hear nuances that I’m not sure I heard, or paid attention to, before. In short, this tiny component—a phono cartridge half the size of my pinky—is providing a whole lot of enjoyment.

When I’m listening to a new piece of equipment—something I don’t do very often, to be honest, because I make my decisions with such care—one subjective test is how often I swap records. If I find myself sitting and listening, often to a whole side of an LP, I know that I’ve found a winner. So now I’m spending hours listening, and rediscovering discs that I know pretty well—and finding new joy because there is more detail, punch, clarity, and sense of being there with so many LPs. I’m very impressed by the Dynavector DV20x20, and I’ll attempt to close out with the reasons why. On classical recordings, I find the overall presence most appealing, closely followed by the punch and sweep of the more exciting passages, and increased refinement of solo violins, female voice, clarinets, oboes, and flutes. On jazz recordings, it’s undoubtedly the crispness of the drum kit—so precise, with just the right sense of attack and decay—though I do love what happens when I listen to Oscar Peterson playing piano, and I know that because I now find it difficult to listen to him as background music. I pay more attention to the music! On rock LPs, it’s the bass and the percussion that gets me, but also the higher tinkering on an electric or pedal steel guitar. When I listen to a singer, I hear nuances that I’m not sure I heard, or paid attention to, before. In short, this tiny component—a phono cartridge half the size of my pinky—is providing a whole lot of enjoyment.

Most of all, I confirmed the importance of patient listening–confirming what I thought I heard by listening to the Goldmark symphony by also listening to jazz by Lee Morgan, vocals by Ricky Lee Jones and Linda Ronstadt, rock and roll jams on the obscure Music from Free Creek (with music by Eric Clapton, Dr. John, Jeff Beck), bringing some old Delaney & Bonnie & Friends recordings back to life. There is a consistency about the listening experience that not only sounds and feels right–amazing how much pure instinct and right brain judgement is involved in confirming my sense that the Insight is the right choice–instinct and behavior. If I notice that I’m just standing next to the turntable, intending to lift the stylus but deciding to listen to just one more song, I know I’m making a good decision.

Most of all, I confirmed the importance of patient listening–confirming what I thought I heard by listening to the Goldmark symphony by also listening to jazz by Lee Morgan, vocals by Ricky Lee Jones and Linda Ronstadt, rock and roll jams on the obscure Music from Free Creek (with music by Eric Clapton, Dr. John, Jeff Beck), bringing some old Delaney & Bonnie & Friends recordings back to life. There is a consistency about the listening experience that not only sounds and feels right–amazing how much pure instinct and right brain judgement is involved in confirming my sense that the Insight is the right choice–instinct and behavior. If I notice that I’m just standing next to the turntable, intending to lift the stylus but deciding to listen to just one more song, I know I’m making a good decision.