Heck, the stores are too busy, and there’s no law that requires all of the good stuff to show up on December 25. Here’s a rundown of fun stuff on the holiday list. And yes, I’m allowing myself just about anything I want, regardless of whether (a) I need it, and (b) something else on the list is, pretty much, the same thing. On Prancer, on Blitzen… (and be sure to scroll down to the Niagara Falls video—it’s amazing!)

Nikon’s new $3,000 Df DSLR, recently announced, available in black or silver. It’s expensive—and it doesn’t include a full-frame sensor, and it’s not 20MP like the best new cameras, but just 16MP instead. Still, it looks really cool, very much like a 1980s era Nikon SLR. There’s all of the expected stuff that you’ll find in most DSLRs costing half or two-third as much, but it’s the holiday, so why not?

A $350 Tascam DR-60D 4-channel linear PCM recorder, or, in short, a digital audio recorder that mounts on a tripod just below your DSLR, it and can record up to four microphones simultaneously. It records with 4 AA batteries.

A Phantom 2 Vision Quadcopter—not the one for $350 that takes a GoPro camera (though that’s cool, too), but the FPV model that costs over $1,000 (FPV = “first person view”). It can fly for nearly a half hour, and the wireless controller (an app for your iOS or Android device) can be 1000 feet from the remote helicopter in flight (but it must be line-of-sight). The app allows you to start and stop video recording from afar. With all sorts of cool stabilization features. This is easily the coolest gift on the list. The more I learn about it, the cooler it seems. Take, for example, this little film made ABOVE Niagara Falls…

Sony’s $800 DEV-3 Digital Recoding Binoculars. I’ve often wondered why most or, at least, many binocs don’t include a video sensor and some storage. Here’s the start of a whole new thing…you can record in HD, or shoot 7MP images, record on SD cards, and enjoy 10x magnification. Is it a camcorder with a 10x zoom? No, better than that. Is it kind-of-like a digital still camera with a pair of 10x lenses? Well, that’s probably closer to it, but the long-term viewing experience through a pair of binocular lenses is far superior to a camera experience. It’s a very good pair of binoculars, and also, a high-quality camera.

For just $200, Røde’s iXY stereo microphones snaps into a iOS device for much-improved sound recording. It’s a much better way to record music, meetings, etc.: a pair of crossed half-inch cardiod condense captures and onboard analog-to-digital conversation in a small package. And, of course, it’s all controlled by an app. You can record up to 24 bit / 96 kHz with the device (warning: a paid app upgrade here for better recording—an odd way to charge customers for quality.)

In the “I already have one, but maybe you don’t” department: you can now buy Zoom’s H4n portable digital recorder for about $170, and that’s about $100 less than before. It’s a terrific little recorder, well-suited to all sort of professional needs. In fact, I wrote a whole article about it a year or two ago.

Finally, I think I’d like to experiment with a Blackmagic Design Cinema Camera, and the starting place might be the $1000 Pocket Cinema camera. The key here is 13 stops of dynamic range, and my ability to use existing micro four thirds lenses (and legacy lenses via adapter). The result of the extended dynamic range (and other features): that irresistible film look. It’s a pocketable camera that can be used to shoot an independent film. Then again, I think I might prefer the $2,000 model. Or, perhaps, because it’s the holiday time (the best time of the year), maybe one of each. Here’s the start of a three-part review worth watching. at least for those who want every possible detail.

There was a wonderful innocence about Harry Nilsson in those days. Like

There was a wonderful innocence about Harry Nilsson in those days. Like  The early days, and the dreadful slide into substance abuse, crappy behavior and, ultimately, death, is told with appropriate accuracy and sensitivity by biographer

The early days, and the dreadful slide into substance abuse, crappy behavior and, ultimately, death, is told with appropriate accuracy and sensitivity by biographer

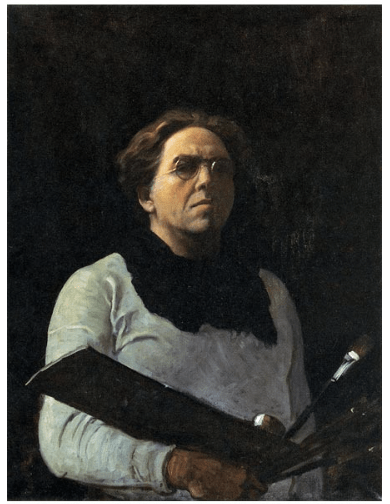

Gosh, I am so tired of hearing the term “selfies.” It’s been named ‘word of the year’ for Oxford University’s Dictionary. You’d think they’d choose something more interesting.

Gosh, I am so tired of hearing the term “selfies.” It’s been named ‘word of the year’ for Oxford University’s Dictionary. You’d think they’d choose something more interesting.

Mostly, I wanted to thank you for reminding me of the special quality of a handwritten letter written, and the even more special quality of a handwritten letter received. It’s been a while.

Mostly, I wanted to thank you for reminding me of the special quality of a handwritten letter written, and the even more special quality of a handwritten letter received. It’s been a while.

The most ambitious track is Secrets of the Sun (Son) featuring wonderful vocal work by formidable performer, vocal arranger and composer

The most ambitious track is Secrets of the Sun (Son) featuring wonderful vocal work by formidable performer, vocal arranger and composer