You may not know the name Paul McGowan. If you’re interested in high-end audio, and/or you listen to a lot of recorded music, Paul is someone you ought to know. He’s the “P” in “PS Audio,” a leading maker of quality loudspeakers. He and his team have designed and built all sorts of audio products. And he’s been doing this for a half-century. That experience is now captured in a library of ten (!) volumes of a series called The Audiophile’s Guide. They’re available as a set (www.theaudiophilesguide.com) and as individual books. Each book is substantial — several hundred pages long, and costs about $40.

There are ten books. They cover, for example, The Stereo, The Loudspeaker, Analog Audio generally, Digital Audio generally, Vinyl, the all-important Listening Room, the Subwoofer, Headphones, Home Theater, and a distilled version of the series called The Collection.

The book about Vinyl is especially helpful. It begins at the beginning: the development and evolution of records, followed by a very clear explanation of “groove modulation” — the way record grooves interact with a phonograph stylus, which leads to a discussion of cutting masters, plating and pressing, and my favorite part, the debate about the quality of records vs. other recorded media. And so, the author eases into groove wall resistance, natural compression curves, and other particulars that make records sound so good — especially when the playback equipment is right.

The sound of vinyl is much affected by the operation of the turntable — the way the motor turns the circular table, for example — and the design of the tonearm. These concepts ride in the background of audiophile discussions, but here, author Paul McGowan shines — his articulate, direct, simple language makes the concepts compressible. The chapter called “Engineering Challenges of Tonearms” is not a lesson in technical engineering, but instead, a 2-page essay that pretty much tells the listener what they might want to know. Cartridges are also confusing and difficult to understand, but here, moving magnets, moving coils, cantilevers and other types of cartridge technology come to life, make sense, and provide the listening with a good basic understanding of what matters and why.

McGowan is equally good on the practice of buying just the right product for your individual purpose. And so: choosing a pre-amplifier, choosing a cartridge, and so on. There’s a turntable setup guide here, too, but I wish it included diagrams. If you’ve heard terms such as tracking force and azimuth, this book provides an easy way to learn the basics.

If you want to listen to music, but you feel as though you ought to know just enough about technology to advance your listening experience, this book series can be a very useful tool.

l, I wondered whether a greater investment would significantly improve the experience of listening to records. As I wondered, I found myself spending $20-30 in record shops specializing in vinyl—not buying the new pristine artisan pressings that seem to cost $25-40, but used copies that cost a tenth as much (so $30 bucks buys 8-10 LPs in surprisingly good condition).

l, I wondered whether a greater investment would significantly improve the experience of listening to records. As I wondered, I found myself spending $20-30 in record shops specializing in vinyl—not buying the new pristine artisan pressings that seem to cost $25-40, but used copies that cost a tenth as much (so $30 bucks buys 8-10 LPs in surprisingly good condition).

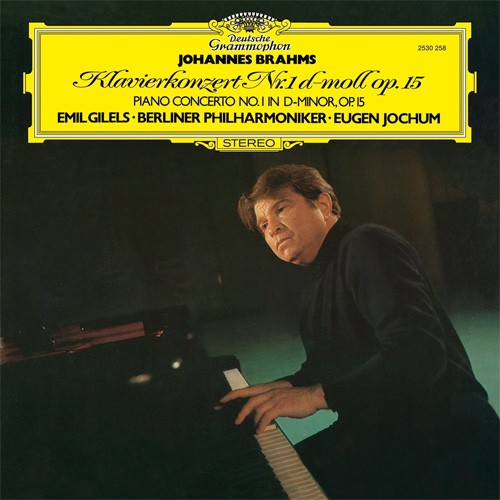

Of course, listening in a well-appointed professional listening room is not much like listening at home. I decided to give the VPI Prime a try. We added the Dynavector DV-20X2L that sounded so good on the Rotel turntable, and connected it to the Sutherland Insight pre-amp, also a wonderful friend for the Rotel. And off we go with a DG recording of Emil Gilels performing Brahms’s first piano concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic—with its bombastic opening, now so clearly rendered with absolute distinction between the instruments, and minimal (if any) congestion in the extreme sequences with what sounds like tons of instruments all blasting their hearts out. Shift to the quieter string and wind sequences, and everything is sweet, present, energetic, really wonderful.

Of course, listening in a well-appointed professional listening room is not much like listening at home. I decided to give the VPI Prime a try. We added the Dynavector DV-20X2L that sounded so good on the Rotel turntable, and connected it to the Sutherland Insight pre-amp, also a wonderful friend for the Rotel. And off we go with a DG recording of Emil Gilels performing Brahms’s first piano concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic—with its bombastic opening, now so clearly rendered with absolute distinction between the instruments, and minimal (if any) congestion in the extreme sequences with what sounds like tons of instruments all blasting their hearts out. Shift to the quieter string and wind sequences, and everything is sweet, present, energetic, really wonderful. And yet, none of that matters. Not when Emil Gilels is playing the piano, and I’m litening to a turntable, a cartridge and a phono stage that were, five months ago, a completely theoretical idea. Now, the sound feels so natural, so effortless, so entirely pleasant, so exhilarating, that I wonder why I waited so long to improve the “analog front end” of an otherwise terrific stereo system.

And yet, none of that matters. Not when Emil Gilels is playing the piano, and I’m litening to a turntable, a cartridge and a phono stage that were, five months ago, a completely theoretical idea. Now, the sound feels so natural, so effortless, so entirely pleasant, so exhilarating, that I wonder why I waited so long to improve the “analog front end” of an otherwise terrific stereo system.

Most of all, I confirmed the importance of patient listening–confirming what I thought I heard by listening to the Goldmark symphony by also listening to jazz by Lee Morgan, vocals by Ricky Lee Jones and Linda Ronstadt, rock and roll jams on the obscure Music from Free Creek (with music by Eric Clapton, Dr. John, Jeff Beck), bringing some old Delaney & Bonnie & Friends recordings back to life. There is a consistency about the listening experience that not only sounds and feels right–amazing how much pure instinct and right brain judgement is involved in confirming my sense that the Insight is the right choice–instinct and behavior. If I notice that I’m just standing next to the turntable, intending to lift the stylus but deciding to listen to just one more song, I know I’m making a good decision.

Most of all, I confirmed the importance of patient listening–confirming what I thought I heard by listening to the Goldmark symphony by also listening to jazz by Lee Morgan, vocals by Ricky Lee Jones and Linda Ronstadt, rock and roll jams on the obscure Music from Free Creek (with music by Eric Clapton, Dr. John, Jeff Beck), bringing some old Delaney & Bonnie & Friends recordings back to life. There is a consistency about the listening experience that not only sounds and feels right–amazing how much pure instinct and right brain judgement is involved in confirming my sense that the Insight is the right choice–instinct and behavior. If I notice that I’m just standing next to the turntable, intending to lift the stylus but deciding to listen to just one more song, I know I’m making a good decision.

AirStash. Simple idea: load some movies on a 8GB or 16GB SD card–the ones you use in a camera that are about the size of a postage stamp–then wirelessly connect the small AirStash device to watch movies (or review documents) on your iPad, iPhone, or Android device. It costs about $125. Use it once and you’ll carry it everywhere, as I do.

AirStash. Simple idea: load some movies on a 8GB or 16GB SD card–the ones you use in a camera that are about the size of a postage stamp–then wirelessly connect the small AirStash device to watch movies (or review documents) on your iPad, iPhone, or Android device. It costs about $125. Use it once and you’ll carry it everywhere, as I do. A ZOOM Q2H2. With cameras and camcorders now built into phones, why buy a small video recorder for $199? Because the sound and the picture quality is outstanding, but the device is small. What do I mean by “outstanding?” Video: 1920×1080, 30p HD. Audio: 24 bit, 96 kHz PCM. Record the results on an SD card.

A ZOOM Q2H2. With cameras and camcorders now built into phones, why buy a small video recorder for $199? Because the sound and the picture quality is outstanding, but the device is small. What do I mean by “outstanding?” Video: 1920×1080, 30p HD. Audio: 24 bit, 96 kHz PCM. Record the results on an SD card.