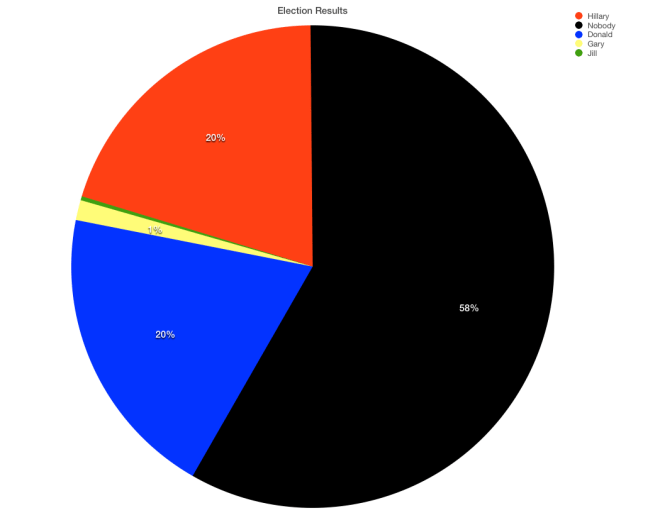

In spite of the abundance of statistics delivered by the news media last night, this information didn’t get much attention.

- About 325 million people live in the U.S., and about 25 million of us are under 18 years old, so 300 million people are old enough to vote.

- Adding the Clinton (59 million) and Trump (59 million) totals, that’s 118 million.

- So: less than 120 million people in the U.S. voted for the two mainstream candidates.

- 60 percent of people 18+ DID NOT VOTE for either of these two candidates.

- Add-in the not-much-mentioned Johnson (4 million) and Stein (1 million), and the total vote is up to 125 million.

- So: the new President of the U.S. was voted into office by less than 20 percent of U.S. citizens 18+ years old.

According to The New York Times, 200 million U.S. citizens were registered to vote in the 2016 election (that is: 1 in 3 Americans are not registered). And, apparently, 75 million people who were registered decided not to vote. Hence, 178M U.S. adult citizens were the majority group in this Presidential election.

Sometimes, I wonder whether adults are more effective voters than children–most children spend their days learning, and some of what they learn is about choosing a leader. If we add 25 million children, then over 200 million U.S. citizens (out of 325 million U.S. citizens) did not vote in this election.

The youthful exuberance is gone, the social awareness is increasing, the production is slicker by 1969’s “Stand” — “you’ve been sitting much too long—there’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong!” – “there’s a midget standing tall, and a giant beside him about to fall!” It feels a bit dated, a golden oldie, a solid memory but the controlled chaos and the crazy audio production is a thing of the past. From the same album (called Stand), there’s “Sing a Simple Song” and “Everyday People”— probably the group’s high water mark— and both of those songs bind the no-holds-barred past with the glossier, socially consciousness future. The same album’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (same lyric, “Don’t call me whitey, nigger”) is a sincere push toward revolution.

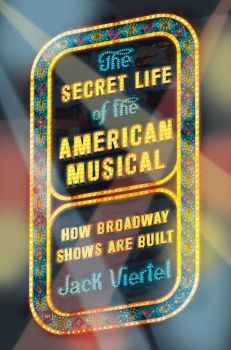

The youthful exuberance is gone, the social awareness is increasing, the production is slicker by 1969’s “Stand” — “you’ve been sitting much too long—there’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong!” – “there’s a midget standing tall, and a giant beside him about to fall!” It feels a bit dated, a golden oldie, a solid memory but the controlled chaos and the crazy audio production is a thing of the past. From the same album (called Stand), there’s “Sing a Simple Song” and “Everyday People”— probably the group’s high water mark— and both of those songs bind the no-holds-barred past with the glossier, socially consciousness future. The same album’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (same lyric, “Don’t call me whitey, nigger”) is a sincere push toward revolution. Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this: Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern. Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

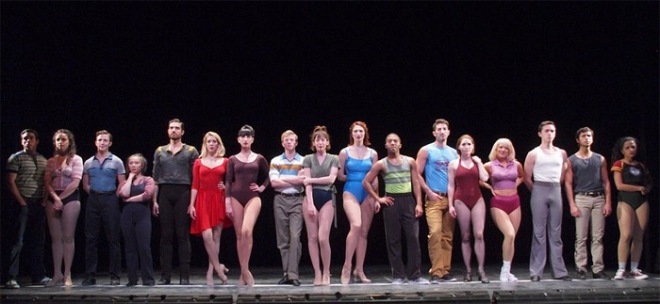

The turnaround story begins, as it ought to begin, with a pitch from a creative professional to a producer. The two remarkable people in this particular scene are Public Theater producer Joseph Papp and choreographer-director Michael Bennett. Reidel: “Bennett arrived at Papp’s office at the Public Theater carrying a bulky Sony reel-to-reel recorder and several reels of tape. He had nearly twenty-four hours of interviews with Broadway dancers. He thought there might be a show somewhere in those hours and hours of tape. He played some of them for Papp. After to listening to the recordings for forty-five minutes, Papp said, ‘OK, let’s do it.”

The turnaround story begins, as it ought to begin, with a pitch from a creative professional to a producer. The two remarkable people in this particular scene are Public Theater producer Joseph Papp and choreographer-director Michael Bennett. Reidel: “Bennett arrived at Papp’s office at the Public Theater carrying a bulky Sony reel-to-reel recorder and several reels of tape. He had nearly twenty-four hours of interviews with Broadway dancers. He thought there might be a show somewhere in those hours and hours of tape. He played some of them for Papp. After to listening to the recordings for forty-five minutes, Papp said, ‘OK, let’s do it.”

Enter the

Enter the  d the corner from the museum is The Four Way Restaurant, where Stax musicians, producers and engineers used to eat, and where I shared a table with a preacher who was touring the South, speaking about how Wal-Mart was destroying the local economy. Fried chicken, fried fish, side dishes of greens and yams. Preacher told me he would be heading next to Clarksdale, then on to Cleveland (Mississippi) and Indianola, just a few hours south. Next morning, I decided to skip a few speeches at a trade show and head for Clarksdale, figuring I’d be back just after lunch. I guess I didn’t anticipate driving down Highway 61, or waiting on Aunt Sarah to do her daily deliveries before serving lunch in what turned out to be one of the few places to buy lunch in the once-vibrant small city of Clarksdale. And if it wasn’t for my visit with Roger Stolle in the

d the corner from the museum is The Four Way Restaurant, where Stax musicians, producers and engineers used to eat, and where I shared a table with a preacher who was touring the South, speaking about how Wal-Mart was destroying the local economy. Fried chicken, fried fish, side dishes of greens and yams. Preacher told me he would be heading next to Clarksdale, then on to Cleveland (Mississippi) and Indianola, just a few hours south. Next morning, I decided to skip a few speeches at a trade show and head for Clarksdale, figuring I’d be back just after lunch. I guess I didn’t anticipate driving down Highway 61, or waiting on Aunt Sarah to do her daily deliveries before serving lunch in what turned out to be one of the few places to buy lunch in the once-vibrant small city of Clarksdale. And if it wasn’t for my visit with Roger Stolle in the