Time to get serious by placing the amplifier, or power amplifier, in its proper context. As the final electronic component in the chain from original recording to loudspeakers, the amplifier’s job is to increase the power of the signal, or simply, to make everything louder. For better or for worse. Better: high quality original recording, high-quality turntable / cartridge / phono stage or CD player, pre-amplifier, and high quality interconnection cables running between these devices. Worse: the inadequacies of the weakest link are amplified, too.

In the previous article, we discussed a $999 Rotel pre-amplifier, the RC-1570. Happily, this component was designed to pair with the same company’s RB-1552 Mk II, also $999. (Each can be used with a component from another company, but they look and sound good together—and they’re available in a choice of silver or black.). The RC-1570 is a 130 watt amplifier—a 200 watt version is available for $600 more as the model RB-1582 Mk II—useful if your loudspeakers require more power.

How much power do you need? The answer depends upon several factors. The first is the size of the room—think cubic feet, not square feet. A small room—let’s say 10 feet by 15 feet with an 8 foot ceiling—that’s 1,200 cubic feet would require about 50 watts per channel, more if you’re driving a pair of speakers with a special power-consumptive design (the Magnepan series of flat panel speakers are an example). A good-sized living room (20 x 20 x 10 feet = 4,000 square feet) requires about 100 watts per channel—more if you play your music loud. Bigger room, more power required. However: if your room’s acoustics are “dead”—tapestries on the walls, lots of soft absorbent furniture, thick carpeting, few exposed reflective surface—you may need more power. And if your room is very “live,” you may need less power.

If this seems complicated, trust your ears. Ask your dealer to arrange an in-house test so that you can listen to the prospective amplifier and loudspeakers in your listening room. You will learn a lot about the relationship between the amp and the speakers. (More about listening rooms in the next article.) Be sure to listen to your own records, your own CDs—music whose sound you know from past experience.

Start with the low register: the bass, the drums, the bass section of the orchestra, the lowest vocal sounds. If the amp is suitable to the room and the speakers, the bass will be clearly defined—and thrilling. If you sense some straining, or graininess, then the amp is insufficient for the speakers’ needs (this is why your in-home demo ought to include a test of an amplifier beyond what you believe you need). Now, listen for the soundstage—the placement of the instruments, the sense that you are listening to a full group, ensemble or orchestra. When the music becomes complicated, does the amplifier keep up, or does the soundstage begin to decompose? Start at a lower volume, then gradually increase. If the music sounds very good at a low level, you’ve got a good match between speakers and amplifier. If the music doesn’t sound as good when the volume increases—is the higher register smooth or does it become edgy (and, perhaps, headache-inducing)? Don’t be afraid to go louder than you might listen to under normal circumstances—you want to push the system near its limits (preferably under dealer supervision so you don’t blow out the speakers). Listen to a variety of recordings in order to expose both strengths and weaknesses. And by all means, step up to a better amp in order to understand what you are and are not buying.

For most listeners, most of the time, the Rotel RB-1552 Mk II will be an ideal choice, but it’s considered an entry level amplifier for high-end audio, as is the competitive Parasound A-23 Halo (also $999) for comparison. If you were to increase your investment to about $2,300, and your room, listening preferences and/or loudspeakers require the additional power, you should certainly consider Parasound’s 250-watt A-21 Halo. And, take note, there is a sister pre-amp ($1,095), the well-reviewed Parasound 2-channel P5.

To learn more about any audio component, download the owner’s manual before you buy. (Click on picture.)

Here, we begin to understand the passions of an audiophile: the resonances of the cello, the timber of the piano, the breath behind the vocals, the feeling of warmth and presence, all of these indescribable factors come together to more than justify the additional investment. It’s tempting to read the engineering background, and to refer to the design of the transformer, or the capacitors, or the overall approach to technology, but for me, none of that matters much. Most equipment in this price class is well-made, and most benefits from sophisticated engineering design, but it’s very difficult for me to understand these technology discussions. And besides, what I hear—and I do spend a lot of time listening, as you should if you’re making this kind of investment—and I’ve learned to trust my ears, my brain’s ability to process the information, and the holistic feeling that each recording seems to offer. I think the Rotel sounds very good, and the Parasound A-23 sounds even better—for all of the reasons described above. They also sound different from one another, but I cannot fairly detail the differences because I listened to these models in different rooms, with different loudspeakers.

Too theoretical? Maybe. We can shift back to the practical side of technology. These amplifiers—typical of their class—offer both RCA and XLR (“balanced”) inputs. It’s best if your pre-amp and your amplifier are both equipped with balanced connection. In the high-end community, there is no clear consensus in favor of balanced connections, so try both to determine which approach you prefer.

Too theoretical? Maybe. We can shift back to the practical side of technology. These amplifiers—typical of their class—offer both RCA and XLR (“balanced”) inputs. It’s best if your pre-amp and your amplifier are both equipped with balanced connection. In the high-end community, there is no clear consensus in favor of balanced connections, so try both to determine which approach you prefer.

The other big decision: tube vs. solid state design. Certainly, tubes can sound sweeter, but solid state may seem less, well, scary. This is a longer discussion for a future article. My short-form recommendation: a tube pre-amp paired with a solid stage amplifier—but there’s lots more to discuss.

If you’d like to dig deeper into the world of amplifiers, that’s a good reason to buy The Complete Guide to High-End Audio by long-time Stereophile writer Robert Harley (now in its fifth edition. Some of the information in the book is fairly technical, but most of it is written for the same reason I’m writing these articles—to help select the best listening equipment.

If you’d like to dig deeper into the world of amplifiers, that’s a good reason to buy The Complete Guide to High-End Audio by long-time Stereophile writer Robert Harley (now in its fifth edition. Some of the information in the book is fairly technical, but most of it is written for the same reason I’m writing these articles—to help select the best listening equipment.

The youthful exuberance is gone, the social awareness is increasing, the production is slicker by 1969’s “Stand” — “you’ve been sitting much too long—there’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong!” – “there’s a midget standing tall, and a giant beside him about to fall!” It feels a bit dated, a golden oldie, a solid memory but the controlled chaos and the crazy audio production is a thing of the past. From the same album (called Stand), there’s “Sing a Simple Song” and “Everyday People”— probably the group’s high water mark— and both of those songs bind the no-holds-barred past with the glossier, socially consciousness future. The same album’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (same lyric, “Don’t call me whitey, nigger”) is a sincere push toward revolution.

The youthful exuberance is gone, the social awareness is increasing, the production is slicker by 1969’s “Stand” — “you’ve been sitting much too long—there’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong!” – “there’s a midget standing tall, and a giant beside him about to fall!” It feels a bit dated, a golden oldie, a solid memory but the controlled chaos and the crazy audio production is a thing of the past. From the same album (called Stand), there’s “Sing a Simple Song” and “Everyday People”— probably the group’s high water mark— and both of those songs bind the no-holds-barred past with the glossier, socially consciousness future. The same album’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (same lyric, “Don’t call me whitey, nigger”) is a sincere push toward revolution. Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this:

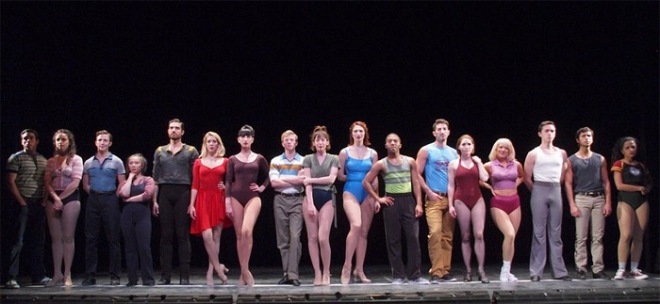

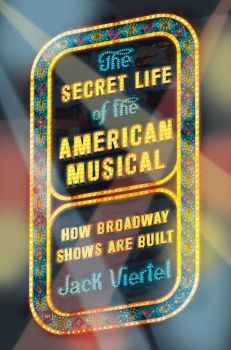

Since overtures “have become a rarity today,” the opening number carries the weight. Originally, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum began with “a sweet little soft shoe about how romance tends to drive people nuts” but that misled the audience because the show was not about romance or charm, but instead, a boisterous vaudevillian take on three Roman comedies. Critics and audiences don’t enjoy mixed messages, so the reviews were lousy and the audiences stayed away. The creative team—a top-notch group that included Larry Gelbart, Stephen Sondheim, Hal Prince, George Abbott, and Burt Shevelove—didn’t know what to do. They asked director Jerome Robbins what he thought. He asked Sondheim (music, lyrics) to write something “neutral… Just write a baggy pants number and let me stage it.” Viertel: “He didn’t want anything brainy or wisecracking, but he did want to tell the audience exactly what it was in for: lowbrow slapstick carried out by iconic character types like the randy old man, the idiot lovers, the battle-axe mother, the wiley slave and other familiar folks. Sondheim wrote “Comedy Tonight” as a typically bouncy opening number, but he couldn’t resist his clever muse, and so, the “neutral” number’s lyrics go like this: Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

Another simulates the movement of a train pulling into River City, Iowa a century ago—serving to introduce the flimflam man named Professor Harold Hill—“Cash for the merchandise, cash for the button hooks, cash for the cotton goods, cash for the hard goods…look, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk, whataytalk?…”to set the stage for The Music Man. Similarly Cabaret begins with the multi-lingual “Wilkommen” and Fiddler on the Roof begins with “Tradition.”

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern.

In Annie, the I Want song is “Maybe”– the orphan dreams of her parents. In Gypsy, the “I Want” song is “Some People,” and in “West Side Story,” it’s “Something’s Comin’” In Hamilton, it’s “My Shot.” It’s “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly” in My Fair Lady and “Somewhere That’s Green” in Little Shop of Horrors. Note the consistency of a place far away as a device to express desire—“ Part of Your World” in The Little Mermaid follows the same pattern. Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters.

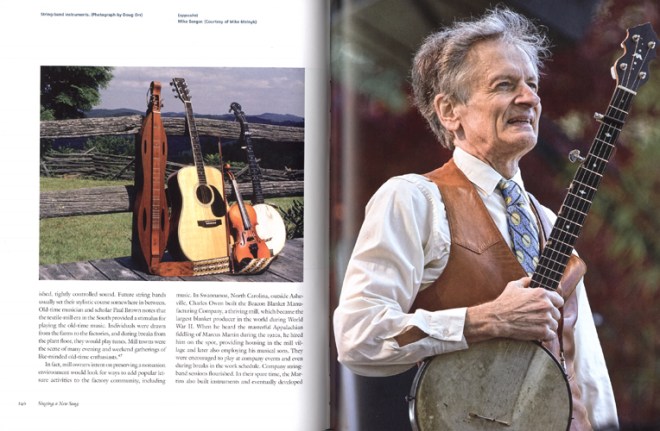

Gee, this is fun. Suddenly, every musical I’ve ever seen makes more sense than ever! I could go on about “The Candy Dish,” “The 11 O’Clock Number” and the construction of the ending, but that would make the whole blog article too long. Pace matters. Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor.

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor. That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.

You may recognize “Blue Diamond Mines,” or may think it sounds familiar (the chorus is similar to to “In the Pines,” a . It’s a bluesy bluegrass tune performed by

You may recognize “Blue Diamond Mines,” or may think it sounds familiar (the chorus is similar to to “In the Pines,” a . It’s a bluesy bluegrass tune performed by