Last week, we spent some time in central Massachusetts–we wanted to buy t-shirts at Hampshire College, and maybe a few children’s books at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. We’ve traveled in this area before. Although we’d noticed the shetl-style architecture of the Yiddish Book Center on the same campus, we never visited. It was a picture-perfect summer day in New England, and the last thing I wanted to do was spend any time indoors, but I inside “just for a few minutes.” I could have spent all day. In fact, I spent the next two days reading Outwitting History, written by  the center’s founder and leader, Aaron Lansky. The book’s subtitle provides only a glimpse of what Lansky, and the Center, has accomplished, and will do: ‘The Amazing Adventures of a Man Who Rescued a Million Jewish Books.’

the center’s founder and leader, Aaron Lansky. The book’s subtitle provides only a glimpse of what Lansky, and the Center, has accomplished, and will do: ‘The Amazing Adventures of a Man Who Rescued a Million Jewish Books.’

Much of the book is devoted to Lansky, his friends, co-workers, and friends collecting the inheritance–the books collected by Jews who had brought their culture from Eastern Europe, and other places, often overcoming obstacles before they landed in their small apartment in Brooklyn, the Bronx or New Jersey. Getting to know these people one by one, Lansky would load his rented truck with shopping bags and cartons of books, often from people whose next step was a retirement home. Just about every visit came with an obligatory range of dishes “cooked special for you” so “you shouldn’t be hungry.” In a typical spread, there would be onion bagels and lox, kasha varnishkes, potato latkes, and lokshn kugl (noodle pudding), plus herring, chopped liver, and other traditional dishes. And conversation. Lots of lots of stories, one about every book, the times, the culture, the memories. In time, Lansky learned to travel as one of a team of three people: “two do do the shlepping and the third to be the Designated Eater. the latter was the really hard job. While the others carried boxes, you had to sit with the host at the kitchen table, listening to stories, sipping endless glasses of tea, and valiently working your way through a week’s worth of dishes cooked ‘special’ just for you…”

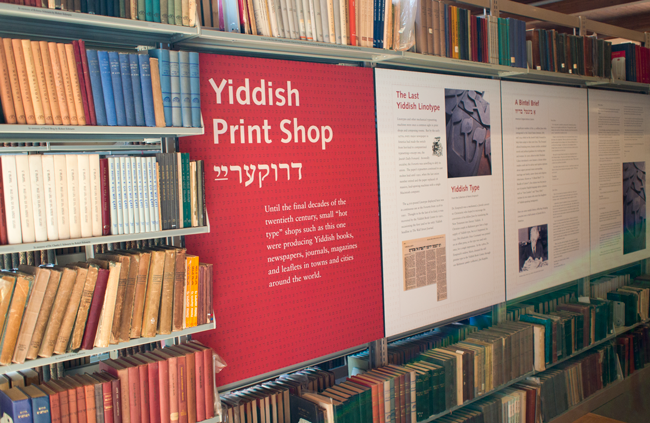

Over two decades or so, Lansky and his colleagues accomplished the impossible–they collected a million copies of Yiddish books. The best ones are now safer than they have ever been; they’re housed in a carved-out mountain that was built as a military facility (remarkably, it’s less than a mile from their Hadley, Massachusetts headquarters). The Center has supplied about 500 university and research libraries with Yiddish book collections (before the Center, only six such collections existed anywhere in North America). If you’re in the area–between Amherst and Northampton, Massachusetts–you can look at any of thousands of books, and you can buy most of them (there are more than enough extra copies around). Some titles are Yiddish translations of popular works by Shakespeare, Hemingway, Poe, Dickinson, and other popular writers. Many are original Yiddish works of fiction, plays, poetry, history books, cookbooks, children’s books, and more. And if you can’t make your way to Massachusetts, you can visit the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library, an online collection of more than 10,000 Yiddish titles, with each book page scanned (most of the original books were published on pulp paper, and some tend to disintegrate with each page turn, so digital technology saved the day).

New Yiddish Library’s most recent title: Moshe Kulbak’s The Zelmenyaners, translated by Hillel Halkin. One of the great comic novels of the twentieth century, The Zelmenyaners describes the travails of a Jewish family in Minsk that is torn asunder by the new Soviet reality.

There is, of course, one problem. The books are written in Yiddish, and must be read in the original language. The Center has a deal with Yale University Press, and some titles are now available in English translation, in book form. More are on the way, but this solution is a minor one.

The major one, of course, is that role of Yiddish has changed, and the people who knew, know, and can claim literacy in Yiddish has been greatly diminished. At one time, more than eleven million people spoke, read, and communicated in Yiddish. That time was 1939, a year before the devastation by the Nazis, and a decade before the the shift into modern times, suburbia, and beginning the end of the old Jewish neighborhoods that once defined so much of New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, and other cities where Yiddish was common currency.

When Lansky was a graduate student in search of a few Yiddish books for graduate school, when he traveled by truck to collect books from crumbling old publishing warehouses and Jewish community centers in the neighborhoods where many Jews once lived, his focus was saving books. Now, the agenda for the Center is even more compelling: books continue to arrive, but the people who can translate them, with appropriate cultural context, are few. It’s one thing to translate the words, quite another to present the story in ways that are both true to the original sensibility and sufficiently interesting to contemporary readers. Yiddish was always a people’s language, informal and spoken at home, never the official language of state affairs or religious ceremonies. As Lansky points out, time and again, all of his scholarship, all of the scholarship gathered by his many friends and associates, all of it pales in comparison with the ninety-year-old man who is sitting in his small Newark apartment, sharing tea and Entenmann’s crumb cake, shopping bag full of books at his side, ready to part with his lifetime of favorite Yiddish novels, books he loves because they were so much a part of his life.

His books are safe now. They will be treated with loving care. They will find a new home. Some will be translated into English so that even those of us who cannot read Yiddish can understand the basics of what they have to say. The work will be done by human translators, and in time, perhaps, by digital translators, too. The love, the sense of what the world was like, the passion, the feeling for the characters and situations created by the great Yiddish writers, poets, playwrights, stage performers, radio performers, singers, these will be more difficult to capture and store inside a mountain in Massachusetts.

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.

That will change, of course. Shame on me for missing this part of my cultural education.

Thank you, Norman Temmelman of Atlantic City, Sorell Skolnik of the Mohegan Colony, Mr. Kupferstein, Marjorie Guthrie (Woody’s wife), and Sam and Leah Ostroff, for helping Aaron Lansky. And thank you, Mr. Lansky for opening the door for me. As I read the books, I will pass them along to friends, to my father and my sons, and attempt, in my small way, to be a link in the chain. I suspect there is a Yiddish proverb beneath all of this, or, at least, a few Yiddish words to describe what’s on my mind, but those words are lost to me. Perhaps I will find a few of them along the way.

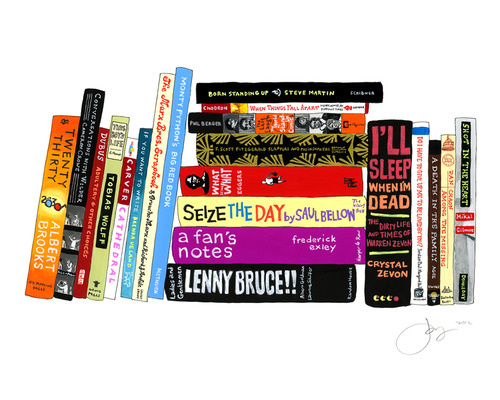

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh.

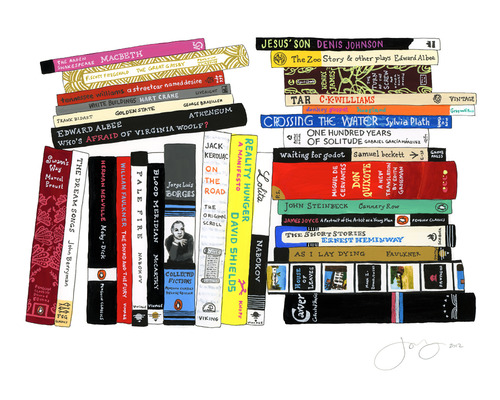

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh. James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

Third in the trilogy is the bright red volume, The Psychology Book. As early as the year 190 in the current era, Galen of Pergamon (in today’s Turkey) is writing about the four temperaments of personality–melancholic, phlegmatic, choleric, and sanguine. Rene Descartes bridges all three topics–Philosophy, Economics and Psychology overlap with one another–with his thinking on the role of the body and the role of the mind as wholly separate entities. We know the name Binet (Alfred Binet) from the world of standardized testing, but the core of his thinking has nothing whatsoever to do with standardized thinking. Instead, he believed that intelligence and ability change over time. In his early testing, Binet intended to capture a helpful snapshot of one specific moment in a person’s development. And so the tour through human (and animal) behavior continues with Pavlov and his dogs, John B. Watson and his use of research to build the fundamentals of advertising, B.F. Skinner’s birds, Solomon Asch’s experiments to uncover the weirdness of social conformity, Stanley Milgram’s creepy experiments in which people inflict pain on others, Jean Piaget on child development, and work on autism by Simon Baron-Cohen (he’s Sacha Baron Cohen’s cousin).

Third in the trilogy is the bright red volume, The Psychology Book. As early as the year 190 in the current era, Galen of Pergamon (in today’s Turkey) is writing about the four temperaments of personality–melancholic, phlegmatic, choleric, and sanguine. Rene Descartes bridges all three topics–Philosophy, Economics and Psychology overlap with one another–with his thinking on the role of the body and the role of the mind as wholly separate entities. We know the name Binet (Alfred Binet) from the world of standardized testing, but the core of his thinking has nothing whatsoever to do with standardized thinking. Instead, he believed that intelligence and ability change over time. In his early testing, Binet intended to capture a helpful snapshot of one specific moment in a person’s development. And so the tour through human (and animal) behavior continues with Pavlov and his dogs, John B. Watson and his use of research to build the fundamentals of advertising, B.F. Skinner’s birds, Solomon Asch’s experiments to uncover the weirdness of social conformity, Stanley Milgram’s creepy experiments in which people inflict pain on others, Jean Piaget on child development, and work on autism by Simon Baron-Cohen (he’s Sacha Baron Cohen’s cousin).