Bobby Watson is a musician’s musician, well-known in some circles, but not a famous jazz saxophone, at least not these days. Those who were paying attention in the mid-1980s, or who have done their research on the best jazz albums of that era, tend to love Appointment in Milano, and Year of the Rabbit; recorded and released nearly twenty years later, Horizon Reassembled is also terrific. Browse Watson’s All Music listing, and you’ll find a half-dozen superior albums by one of jazz’s best saxophone players. Watson’s Check Cashing Day surprised me by showing up in the mail last week. Made me happy. Made me think, too. You can listen to some samples here. Let me tell you more about it.

Bobby Watson is a musician’s musician, well-known in some circles, but not a famous jazz saxophone, at least not these days. Those who were paying attention in the mid-1980s, or who have done their research on the best jazz albums of that era, tend to love Appointment in Milano, and Year of the Rabbit; recorded and released nearly twenty years later, Horizon Reassembled is also terrific. Browse Watson’s All Music listing, and you’ll find a half-dozen superior albums by one of jazz’s best saxophone players. Watson’s Check Cashing Day surprised me by showing up in the mail last week. Made me happy. Made me think, too. You can listen to some samples here. Let me tell you more about it.

Recorded to remember Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech fifty years ago, Watson’s creative partner on this project is a fellow artist from Kansas City, Glenn North. He’s a spoken word performer, and poet who does his best to speak the truth (that second link provides a good example of his work—listen with your ears, and don’t worry about the so-so video quality). Mr. North is also the education manager at the Kansas City Jazz Museum, a kin with Watson who has doubled on the academic side for decades. North’s work is accessible with whiffs of hip-hop language and cadence, straight talk that carries the right messages:

Black is a flock of one hundred crows flying across the moon.

Black is hot water, cornbread and black-eyed peas served with a wooden spoon.

Black is the floor of the Atlantic Ocean covered with fifty million ancestral bones.

Black is the thundercloud over The Congo as the panther starts to moan.

Black is what was before before, when there was no time or space.

Black is the mistreated, the misunderstood, the magnificently beautiful race.

Black is a thousand midnights buried beneath the cypress swamp.

Black is four nappy-headed boys cruising in a beat-up Mitsubishi Galant.

Black is a thousand hornets ready to attack.

And even though Black ain’t went nowhere, tonight, Black is back.

Good poem, but so much better with the beautiful soundtrack provided by the sweet sound of Bobby Watson’s saxophone and the bowed bass so handsomely played by Curtis Lundy. This is what concept albums ought to be, maybe used to be, and I now understand that I miss them. Music with a purpose, a point of view, something to say, something well-said. Watson’s quartet provides some straight-ahead jazz tracks, perhaps the best of them is “A Blues of Hope,” but there are plenty more.

The most ambitious track is Secrets of the Sun (Son) featuring wonderful vocal work by formidable performer, vocal arranger and composer Pamela Baskin-Watson (his wife), Glenn North’s spoken word at its confident best, and a splendid arrangement that allows the quartet to shine.

The most ambitious track is Secrets of the Sun (Son) featuring wonderful vocal work by formidable performer, vocal arranger and composer Pamela Baskin-Watson (his wife), Glenn North’s spoken word at its confident best, and a splendid arrangement that allows the quartet to shine.

The more I listen, the more I appreciate what this ensemble has done. Sure, it’s a wonderful jazz album, but Watson does that just about every time. He’s a pro, he’s been doing this forever, and he’s gifted. But there’s a lot more heart and soul here, a coherent focus, a grown-up reflection on what has happened, and has not happened, and what has decidedly not happened, since Martin gave the speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial. More from Glenn North, again presented with Watson’s spot-0n soundtrack.

I’m tired of welfare handouts and being played the fool.

I’m also tired of waiting for my forty acres and a mule.

Tired of being mis-educated in this country’s so-called schools.

Ain’t none of them teachers talking about my forty acres and a mule.

I bet you’d sing a different tune if it was me that owed something to you.

Save all the double-talk, and give me my forty acres and a mule.

You keep smiling in my face, but I know your heart is cruel.

Why else wouldn’t you give me my forty acres and a mule?

And why am I the one always getting arrested when you’re the one breaking all the rules?

You know my next question.

Where the hell is my forty acres and a mule?

I’ve been oppressed for over four hundred years, been the object of ridicule.

The least you could do is break me off my forty acres and a mule.

Compared to what you’ve done to me, what I’m requesting is miniscule.

You should be glad that what I’m asking for is forty acres and a mule.

The bill is up to four trillion dollars now and the man is way past due.

What do I have to do to get my forty acres and a mule?

The poet and spoken word artist Glenn North.

After writing several articles about intellectual property and fairness, I hope this brief excursion into Glenn North’s poetry is okay with him (if it’s not, I hope he will contact me so I can remove it or otherwise change the presentation). I wanted you to get a sense of what this people have done, and because I think it matters, and because I think it ought to set the stage for more concept albums about important ideas, I provided more than I might otherwise have done.

Hey, this is good work, and it deserves recognition. If you’re trying to track down something interesting and different to buy for friends or family, this is a good choice to add to the list. Normally, I hate it when a website starts playing music when I arrive. In the case of www.bobbywatson.com, I had the opposite reaction. Turn it up and enjoy.

However reasonable, that’s no longer the way things work. Now, it seems, making the world a better place is reason enough to freely distribute copyrighted work without permission of the copyright holder. Here’s the logic and the new law of the land as set forth by

However reasonable, that’s no longer the way things work. Now, it seems, making the world a better place is reason enough to freely distribute copyrighted work without permission of the copyright holder. Here’s the logic and the new law of the land as set forth by

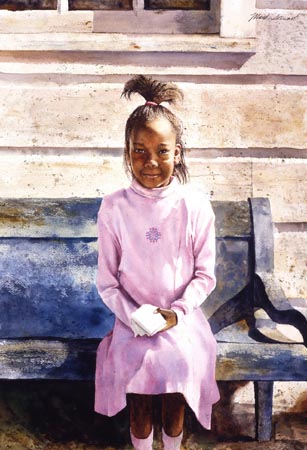

Every once in a while, I’ll find an artist on the web whose work I truly admire. I recently stumbled upon a Texas watercolorist named Mark Stewart, and I thought you might enjoy seeing some of his work. Of course, there’s no reason why you should read any of what I have to say… just go directly to his

Every once in a while, I’ll find an artist on the web whose work I truly admire. I recently stumbled upon a Texas watercolorist named Mark Stewart, and I thought you might enjoy seeing some of his work. Of course, there’s no reason why you should read any of what I have to say… just go directly to his

On September 20, 2013, the U.S. Postal Service was ordered to pay well over a half-million dollars to Frank Gaylord. He is a sculptor, the artist responsible for the

On September 20, 2013, the U.S. Postal Service was ordered to pay well over a half-million dollars to Frank Gaylord. He is a sculptor, the artist responsible for the