While I admit to not being here for about a year—apologies, but I’ve been having fun doing cool stuff—I tend to enjoy knowing precisely where I am at any given moment.

For example, about two weeks ago, I visited Bohemian National Hall on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. It’s an impressive old building, one of the few surviving ethnic community halls that provided comfort and culture to ethnic communities on the island. BNH has become the New York home of the Digital Hollywood conferences. This time, the focus was Virtual Reality, and its kin, Artificial Reality.

The New York Times now employs a Virtual Reality Editorial Team. They have completed about five projects, each involving high technology and a cardboard box. For the uninitiated, the cardboard box is used to house a smart phone, which, in turn, displays oddly distorted images that can be seen through a pair of inexpensive stereoscopic lenses. To hear the soundtrack, ear plugs are required.

The New York Times now employs a Virtual Reality Editorial Team. They have completed about five projects, each involving high technology and a cardboard box. For the uninitiated, the cardboard box is used to house a smart phone, which, in turn, displays oddly distorted images that can be seen through a pair of inexpensive stereoscopic lenses. To hear the soundtrack, ear plugs are required.

VR is not 3DTV, but it shares some characteristics with that dubious invention. You are a camera with perhaps sixteen lenses. As you turn your head, the stitched-together video imagery simulates reality: you can turn from side to side, up to down, all around, and gain a sense of what’s all around you. (One of the new VR production companies showed off a home-brewed VR camera setup: 16 GoPro cameras set in a circle the size of a frisbee, with several more pointing up and down, all recording in synchronization, collectively requiring an enormous amount of video storage.)

VR provides is a wonderful sense of immersion, and a not-so-good sense of disorientation.

When there is something to explore, immersion is a spectacular invention. For example, diving in deep water and seeing all sorts of aquatic life. Or, walking in a forest. Or being in just the right place at the right time at a sporting event or political convention—you know, being there.

But where, exactly, is “there?” And precisely when should do you want to be there? I never thought about it much before, but the television or film or stage director makes that decision for you—“look here now!” And after that, “look here.” With VR, you can explore whatever you want to explore, but you are likely to miss out on what someone else believes to be important. There is freedom in that, but there is also tremendous boredom—that’s the point of employing a director, a guide, a writer, a performer—to compress the experience so that it is memorable, informative, and perhaps, entertaining.

Tidbits from the NY Times panel: “VR film is not a shared experience—each audience member brings his or her own perspective”…”the filmmaker must let go of quick cuts, depth of field, and cannot control what the viewer may see”…”how do we tell a story that may be experienced in different ways by different people?”…”there is far less distortion imposed by the storyteller”…”much of what would normally be left out is actually seen and heard in VR.”

In some ways, letting the viewer roam around and reach his or her own conclusions is both the opposite of journalism and, perhaps, its future. In an ideal sense, journalism brings the viewer to the place, but that never really happens. Is it useful to place the viewer in the observational role of a journalism, or does the journalist provide some essential editorial purpose that helps the viewer through the experience in an effective, efficient, compelling way?

Is all of this a new visual language and the first step toward a new way of using media, or a solution in search of a problem?

After a very solid day of listening to panelists whose expertise in VR is without equal, I left with a powerful response to that question: “who knows?”

Jenny Lynn Hogg, who is studying these and related phenomena, might know. “Imagine if the Vietnam War Memorial could speak.” Take a picture of any name on the wall, and your smart phone app will retrieve a life story in text, images, video and other media. Is this VR, AR, or something else? Probably not VR, not in the sense of the upcoming Oculus Rift VR headset, but probably AR, or Augmented Reality. What’s that? In essence, turning just about everything we see into a kind of QR Code that links real world objects with digital editorial content. Quicker, more efficient, and more of a burst of information that a typical web link might provide, AR is often linked to VR because, in theory, they ought to be great friends. As you’re passing through a VR environment, AR bits of information appear in front of your eyes.

Although AR was less of a buzz than VR, I think I could fall in love with AR—provided that I could control the messages coming into my field of view, I really like the idea of pointing my smart phone at something, or someone, and getting more information about it, or him or her.

VR, not so much, at least not yet. I’m not enthralled with wearing the headgear—even if it reduces itself from the size of a quart of milk to the design of Google Glass—but that’s not the issue. VR is disorienting, a problem now being deeply researched because the whole concept requires that your perceptive systems work differently. I certainly believe VR is worthy of experimentation to determine VR’s role in storytelling, journalism, gaming, training, medical education, filmmaking, but mostly, to discover what it’s like to be there without being there. We’ll get there (which there? oh, sorry, a different there) by playing with the new thing, trying it out, screwing up, finding surprising successes, and spending a ton of investment money that may, in the end, lead to a completely unexpected result.

Through it all, sitting in that beautiful building, I couldn’t help but wonder what its original inhabitants would have made of our discussion—people who were already gone by the time we invented digital, Hollywood, radio, television, the movies, the internet, videogames and, now, virtual reality. Wouldn’t it be fun to bring them back, to recreate their world, to allow me to walk down Third Avenue in 1900 and just explore? Yup. Fun. And in today’s terms, phenomenally expensive. Tomorrow, maybe, not so much.

Moving from the old world of traditional broadcast networks through hybrid innovators including cable networks then into the new world of internet services and alternative funding models, she covers the waterfront. There are interviews with knowledgable leaders from Netflix, Kickstarter, HBO, and other companies whose work matters a great deal in 2015.

Moving from the old world of traditional broadcast networks through hybrid innovators including cable networks then into the new world of internet services and alternative funding models, she covers the waterfront. There are interviews with knowledgable leaders from Netflix, Kickstarter, HBO, and other companies whose work matters a great deal in 2015. Nowadays, most cable networks are coming to the same conclusion: their future is going to be defined by original programming (scripted and unscripted, both have their place), and by events (which tend to work only sometimes, in part because they’re expensive and also because they’re difficult to construct with any frequency). So there’s the conundrum for the deeper future: as each cable network, and each subscription service, develops and markets their own unique programs, the audience becomes that much more fragmented. The pie slices become smaller, the ability for any individual player to make an impact becomes that much more challenging.

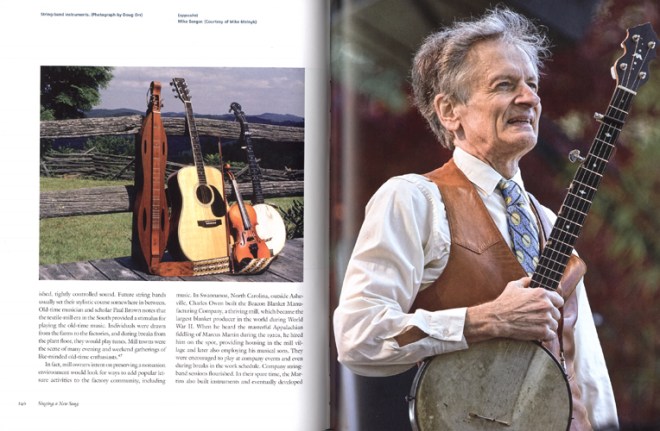

Nowadays, most cable networks are coming to the same conclusion: their future is going to be defined by original programming (scripted and unscripted, both have their place), and by events (which tend to work only sometimes, in part because they’re expensive and also because they’re difficult to construct with any frequency). So there’s the conundrum for the deeper future: as each cable network, and each subscription service, develops and markets their own unique programs, the audience becomes that much more fragmented. The pie slices become smaller, the ability for any individual player to make an impact becomes that much more challenging. Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

In book, lecture and conversation, Scott McCloud has taught me a lot. But it’s one thing to be a teacher and another to be the creator of the material. The expectations become unreasonably high. The student wants to see every lesson incorporated in exquisite elegant prose and picture. The story must be perfect. The storytelling, better than perfect.

In book, lecture and conversation, Scott McCloud has taught me a lot. But it’s one thing to be a teacher and another to be the creator of the material. The expectations become unreasonably high. The student wants to see every lesson incorporated in exquisite elegant prose and picture. The story must be perfect. The storytelling, better than perfect. As David tells his story, the evidence of Scott’s visual storytelling skill propels the sense of reality. There are extreme close-ups and wide streetscapes, frames without dialog that communicate more than those with words, and an interesting isolation technique in which David is fully inked against a world that is rendered only in sketch form. There’s a girl, of course, an angel of sorts, and as in the second act of Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, a difficult-to-fathom big city art scene (Scott and Stephen wrestle with some similar themes.) Main character David tells us that he hates parties and by extension, the whole scene, but those pages are among Scott’s very finest: a crowded multi-page sequence where you can feel the energy of a noisy large-scale party and the frustration in coping with the idiots who won’t leave you alone while you’re trying to keep some girl within your visual range, while you’re trying to chase her before she’s gone forever. (Gee, he does this well!)

As David tells his story, the evidence of Scott’s visual storytelling skill propels the sense of reality. There are extreme close-ups and wide streetscapes, frames without dialog that communicate more than those with words, and an interesting isolation technique in which David is fully inked against a world that is rendered only in sketch form. There’s a girl, of course, an angel of sorts, and as in the second act of Stephen Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, a difficult-to-fathom big city art scene (Scott and Stephen wrestle with some similar themes.) Main character David tells us that he hates parties and by extension, the whole scene, but those pages are among Scott’s very finest: a crowded multi-page sequence where you can feel the energy of a noisy large-scale party and the frustration in coping with the idiots who won’t leave you alone while you’re trying to keep some girl within your visual range, while you’re trying to chase her before she’s gone forever. (Gee, he does this well!) For me, that’s the treat, same as reading Understanding Comics, same as watching Scott lecture, same as spending time with him. We’re living in a world filled with stories and ideas, and clever ways of communicating. If it’s all as simple as A-B-C, then the magic isn’t so magical. Life’s more complicated than a straight series of logical events—and that’s the beauty of a well0-crafted graphic novel. No shopping mall cinema audiences to satisfy with a clearly articulated happy ending. No need for extreme helicopter crashes or uncomfortable explosions punctuated with graphic violence. The story can be personal, it can be told by a single storyteller (provided the storyteller is willing and able to spend several years writing and drawing his epic), and it can be somewhat nonlinear. With that, a reader’s note: do it in one day. That is, find yourself a good stormy day, turn off the cell phone, and just lose yourself. Don’t think too much—just allow the storyteller control your mind for a few hours. We do this for movies all the time—with this book, you don’t want to disengage. You want to pay attention, and grab the ideas as they’re unfolding, then return to study the craft. Last weekend, I read the book. Today, a Saturday, I returned to study the construction of the visual sequences, the use of characters, my favorite scenes and how they were put together.

For me, that’s the treat, same as reading Understanding Comics, same as watching Scott lecture, same as spending time with him. We’re living in a world filled with stories and ideas, and clever ways of communicating. If it’s all as simple as A-B-C, then the magic isn’t so magical. Life’s more complicated than a straight series of logical events—and that’s the beauty of a well0-crafted graphic novel. No shopping mall cinema audiences to satisfy with a clearly articulated happy ending. No need for extreme helicopter crashes or uncomfortable explosions punctuated with graphic violence. The story can be personal, it can be told by a single storyteller (provided the storyteller is willing and able to spend several years writing and drawing his epic), and it can be somewhat nonlinear. With that, a reader’s note: do it in one day. That is, find yourself a good stormy day, turn off the cell phone, and just lose yourself. Don’t think too much—just allow the storyteller control your mind for a few hours. We do this for movies all the time—with this book, you don’t want to disengage. You want to pay attention, and grab the ideas as they’re unfolding, then return to study the craft. Last weekend, I read the book. Today, a Saturday, I returned to study the construction of the visual sequences, the use of characters, my favorite scenes and how they were put together.

This is going to take about fifteen minutes, but I think it’s worth the time.

This is going to take about fifteen minutes, but I think it’s worth the time.

Walter Isaacson is one of the smarter people in the media industry. As a keynote speaker for this past week’s Digital Book World conference, he talked about the limitations of his most recent book,

Walter Isaacson is one of the smarter people in the media industry. As a keynote speaker for this past week’s Digital Book World conference, he talked about the limitations of his most recent book,  For example, maybe a digital book is not a book at all, but a kind of game. Scholastic, a leader in a teen (YA, or Young Adult) fiction publishes a new book in each series at four-month intervals. The publisher wants to maintain a relationship with the reader, and the reader wants to continue to connect with the author and the characters. So what’s in-between, what happens during those (empty) months between reading one book and the publication of the next one in the series? And at what point does the experience (a game, a social community) overtake the book? NEVER! — or so says a Scholastic multimedia producer working in that interstitial space. The book is the thing; everything else is secondary. In fact, I don’t believe him—I think that may be true for some books, but the clever souls at Scholastic are very likely to come up with a compelling between-the-books experience that eventually overshadows the book itself.

For example, maybe a digital book is not a book at all, but a kind of game. Scholastic, a leader in a teen (YA, or Young Adult) fiction publishes a new book in each series at four-month intervals. The publisher wants to maintain a relationship with the reader, and the reader wants to continue to connect with the author and the characters. So what’s in-between, what happens during those (empty) months between reading one book and the publication of the next one in the series? And at what point does the experience (a game, a social community) overtake the book? NEVER! — or so says a Scholastic multimedia producer working in that interstitial space. The book is the thing; everything else is secondary. In fact, I don’t believe him—I think that may be true for some books, but the clever souls at Scholastic are very likely to come up with a compelling between-the-books experience that eventually overshadows the book itself.

It’s a salad with the obvious fresh greens and toasted scallops, smaller than the ones we find in the U.S., and a bit saltier, too. There are bits of a local bacon, too, which enhances the salty favor. The sauce is a red pepper puree, which adds the necessary sweetness to balance the salty flavor. Bit of polenta toast complete the dish.

It’s a salad with the obvious fresh greens and toasted scallops, smaller than the ones we find in the U.S., and a bit saltier, too. There are bits of a local bacon, too, which enhances the salty favor. The sauce is a red pepper puree, which adds the necessary sweetness to balance the salty flavor. Bit of polenta toast complete the dish.

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor.

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor. That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.