Although the idea of writing a book about books and bookstores for people who enjoy books seems to be both precious and redundant, I find browsing, then reading, these books to be irresistible. The newest in this genre is A Booklover’s Guide to New York, by which author Cleo Le-Tan and illustrator Pierre Le-Tan seem to mean not the state of New York, nor most of the city of New York, but instead, the island of Manhattan. And that’s just fine: few places on earth contain a richer assortment of delights for people who love books.

Although the idea of writing a book about books and bookstores for people who enjoy books seems to be both precious and redundant, I find browsing, then reading, these books to be irresistible. The newest in this genre is A Booklover’s Guide to New York, by which author Cleo Le-Tan and illustrator Pierre Le-Tan seem to mean not the state of New York, nor most of the city of New York, but instead, the island of Manhattan. And that’s just fine: few places on earth contain a richer assortment of delights for people who love books.

The book is set up as a combination of a tour and a series of conversations. The first stop is The Mysterious Bookshop, down in TriBeCa, relocated from further uptown, accurately described as “a homey destination” and “a haven for any crime, suspense and thriller reader.” Next page: an interview with Otto Penzler, who owns the shop, and founded Mysterious Press back in the mid-1970s. It’s fun to read his back story–so many people who live in NYC have a backstory–after he started the publishing house, and it succeeded, he decided to open a shop without knowing anything at all about starting or operating a retail enterprise. What was the key to success?: women started writing popular mystery fiction, and that attracted more female readers. He describes Manhattan as “ground zero” for mystery.

Within walking distance: Poet’s House at 10 River Terrace, which has been operating for three decades, “still prides itself on “bringing world-renowned poets to new audiences. And: Richardson, at 325 Broome St., owned by Andrew Richardson, who also publishes a magazine (same name as the shop), with a selection that is “either deeply intellectual, aesthetically pleasing, or highly sophisticated.” And sometimes, erotic. This is not just a book filled with pages about bookstores; the Seward Park Library is one of several public libraries. Opened in 1909, it’s located in Chinatown, which tends to be busy much of the day and night, but here, there is quiet. And a lot of books. And all of the modern conveniences. Museums get their due, too. The first is the Tenement Museum, located at 103 Orchard Street (all of the places in this paragraph are walkable from one another, but subways and buses can shorten the travel times). The museum offers guided tours of life more than a century ago in lower Manhattan, a time when poor European immigrants lived in close quarters. Of course, it includes a specialist bookstore.

Within walking distance: Poet’s House at 10 River Terrace, which has been operating for three decades, “still prides itself on “bringing world-renowned poets to new audiences. And: Richardson, at 325 Broome St., owned by Andrew Richardson, who also publishes a magazine (same name as the shop), with a selection that is “either deeply intellectual, aesthetically pleasing, or highly sophisticated.” And sometimes, erotic. This is not just a book filled with pages about bookstores; the Seward Park Library is one of several public libraries. Opened in 1909, it’s located in Chinatown, which tends to be busy much of the day and night, but here, there is quiet. And a lot of books. And all of the modern conveniences. Museums get their due, too. The first is the Tenement Museum, located at 103 Orchard Street (all of the places in this paragraph are walkable from one another, but subways and buses can shorten the travel times). The museum offers guided tours of life more than a century ago in lower Manhattan, a time when poor European immigrants lived in close quarters. Of course, it includes a specialist bookstore.

Let’s head to midtown. It’s a healthy walk, about two miles north, but it’s quick and easy to hop on the subway. Mostly, this is a busy business district with lots of skyscrapers. My favorite bookstore–the Gotham Book Mart–is among the many shops that are no longer there. But there are plenty of places to visit, and perhaps, buy even more books. If you’re staying overnight, there’s the Library Hotel, 299 Madison Avenue at 41st Street, one of a growing number of hotels with their own collections of books for guests (these are popping up all over the world). The Morgan Library & Museum is a notable Manhattan landmark, and “originally the private library of one of America’s most notable financiers, Pierpont Morgan.” The Morgan also hosts special book-related events and other arts events. It is simply a stunning place. Even more fun: The Drama Book Shop, filled with scripts, scores, and all things theater. Under new ownership–Lin-Manuel Miranda and several of his Hamilton cronies–a new shop opens soon. A short walk leads to the main branch of The New York Public Library, at 42nd Steet and Fifth Avenue, with its awesome map room, classic reading room, and so many places you’ve seen in magazines and in movies. Next, it’s over to Algonquin Hotel, 59 West 44 Street, where “right after World I, a group of rather intelligent and witty twenty-something New York writers, critics, and actors, and nicknamed themselves ‘The Vicious Circle,” and included NY Times theater critic Alexander Woolcott, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and Robert E. Sherwood.

As time and interest allow, there’s John Steinbeck’s apartment at 190 East 72 Street, walkable but again, a subway is faster. And if you want to further explore Manhattan’s Upper East Side, check the schedule for the 92nd Street Y, 1395 Lexington Avenue, because there are often authors and various performers on stage discussing their work: in March, the list includes novelist Zadie Smith, Maria Kalman on her new book about Alice B. Toklas, film director Barry Sonnenfeld talking about his new book with Jerry Seinfeld, E.J. Dionne, Hilary Mantel, Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn on their new book, a lot of musical performances, and more. Right nearby: La Librairie des Enfants, a charming lending library, and an informal community center. Also in the neighborhood: Kitchen Arts & Letters at 1435 Lexington Avenue, offering not only cookbooks but tons of books about food history and related topics

As time and interest allow, there’s John Steinbeck’s apartment at 190 East 72 Street, walkable but again, a subway is faster. And if you want to further explore Manhattan’s Upper East Side, check the schedule for the 92nd Street Y, 1395 Lexington Avenue, because there are often authors and various performers on stage discussing their work: in March, the list includes novelist Zadie Smith, Maria Kalman on her new book about Alice B. Toklas, film director Barry Sonnenfeld talking about his new book with Jerry Seinfeld, E.J. Dionne, Hilary Mantel, Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn on their new book, a lot of musical performances, and more. Right nearby: La Librairie des Enfants, a charming lending library, and an informal community center. Also in the neighborhood: Kitchen Arts & Letters at 1435 Lexington Avenue, offering not only cookbooks but tons of books about food history and related topics

What about the other boroughs? Sure, there are a few pages about the Bronx (2 pages, plus a good interview with local author Richard Price), Brooklyn (The Center for Fiction–moved after two centuries in Manhattan, The Central Library, which is not part of the New York Public Library but a magnificent enterprise of its own) and Queens (a lovely story about fulfilling the need for neighborhood bookstores–Kew & Willow Books).

There are some photographs, but they tend to be small and suggest snapshots. Better are the pen-and-ink illustrations that do not attempt to support the text in a literal way. Instead, the pictures provide a sense of place, offer little piles of books and the occasional bookworm. Think about the use of spot illustrations in the New Yorker magazine–but add spot color.

(Note: New Yorker illustrator Pierre Le-Tan died in October 2019.)

The success of Third Fridays encouraged the city leaders to pursue a larger dream. They applied to serve as the host city for the

The success of Third Fridays encouraged the city leaders to pursue a larger dream. They applied to serve as the host city for the  We started out with an acoustic band out of Pittsburgh called

We started out with an acoustic band out of Pittsburgh called

The variety of things to do at a folk festival is striking, and provocative. We wandered from Appalachian storytelling to the juke joint electric guitar of

The variety of things to do at a folk festival is striking, and provocative. We wandered from Appalachian storytelling to the juke joint electric guitar of

We missed them onstage, but we spent an hour chatting with the

We missed them onstage, but we spent an hour chatting with the

Professor Susan Engel remembers growing up. She recalls small details. Not only did she eat bugs, she remembers when and where, and which bugs she ate (potato bugs). As a pre-schooler, she remembers watching TV while sitting under the ironing board, comfortably asking all sorts of questions of Nonna, who was ironing the family’s clothes above her. In a one-room school house, Mrs. Grubb’s imbalanced approach to curiosity and education began a lifetime of inquiry. One of Professor Engel’s works-in-progress is a evaluative measure for curiosity, which seems consistent with the way most people think about school in the 21st century, and, to me, wildly counterintuitive.

Professor Susan Engel remembers growing up. She recalls small details. Not only did she eat bugs, she remembers when and where, and which bugs she ate (potato bugs). As a pre-schooler, she remembers watching TV while sitting under the ironing board, comfortably asking all sorts of questions of Nonna, who was ironing the family’s clothes above her. In a one-room school house, Mrs. Grubb’s imbalanced approach to curiosity and education began a lifetime of inquiry. One of Professor Engel’s works-in-progress is a evaluative measure for curiosity, which seems consistent with the way most people think about school in the 21st century, and, to me, wildly counterintuitive.

The tiger is George’s Clemenceau, great friend of hedgehog Claude Monet, who turns out to be the last of the impressionists. The story picks up long after Monet had moved to his lovely garden home in Giverny, about halfway upriver from Paris on the way to Rouen. And may recall Rouen because that’s home to the ancient cathedral that Monet painted more than thirty times under all sorts of light. Monet was that kind of artist—obsessive, meticulous, perfectly happy to spend endless hours interpreting the London fog or wheat stacks (similar to hay stracks) not far from his home in the country. When author Ross King picks up Monet’s story, the artist is less enthusiastic about travel, but eager to serve and take healthy part in a lavish lunch before touring the beautiful Giverny garden, visiting the pond and lily pads, or showing off his latest work, most often very large paintings. By now, Monet is far more active than many men his age, still active enough to build a new studio adjacent to the house and fill it with new paintings. Cataracts and other health problems make seeing, and therefore painting with the specific colors he requires, a terrifying challenge. And there is a Great War on the horizon, so his life’s work may be destroyed by the German forces already notorious for precisely this sort of mayhem.

The tiger is George’s Clemenceau, great friend of hedgehog Claude Monet, who turns out to be the last of the impressionists. The story picks up long after Monet had moved to his lovely garden home in Giverny, about halfway upriver from Paris on the way to Rouen. And may recall Rouen because that’s home to the ancient cathedral that Monet painted more than thirty times under all sorts of light. Monet was that kind of artist—obsessive, meticulous, perfectly happy to spend endless hours interpreting the London fog or wheat stacks (similar to hay stracks) not far from his home in the country. When author Ross King picks up Monet’s story, the artist is less enthusiastic about travel, but eager to serve and take healthy part in a lavish lunch before touring the beautiful Giverny garden, visiting the pond and lily pads, or showing off his latest work, most often very large paintings. By now, Monet is far more active than many men his age, still active enough to build a new studio adjacent to the house and fill it with new paintings. Cataracts and other health problems make seeing, and therefore painting with the specific colors he requires, a terrifying challenge. And there is a Great War on the horizon, so his life’s work may be destroyed by the German forces already notorious for precisely this sort of mayhem. He is also an extraordinarily difficult, insecure, proud man who feels that he must do more for France, provided that doing more is possible on his own exacting terms.

He is also an extraordinarily difficult, insecure, proud man who feels that he must do more for France, provided that doing more is possible on his own exacting terms. Author

Author

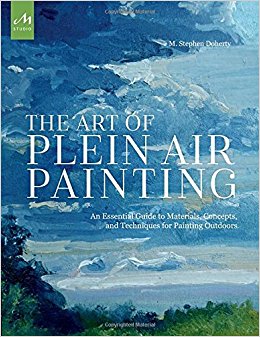

Willingness to paint outdoors requires more than straightforward skills. It requires a real desire to be part of the place that you’re painting. It’s a mindset, an attitude, a combination of willingness to be flexible and a desire to capture the light and sensibility that you cannot quite find by referring to a photograph. That’s why the book begins not with a discussion of portable easels (that comes later), but with an insightful illustrated essay posing as Chapter 1: “Why Paint Outdoors?” He focuses on the mental game and also shows himself in the game, on the street, easel set up just beside a construction site so he can get just the right view, messy paint-covered sweatshirt and slight scowl and all. He ponders how much of the work needs to be done outdoors–if you finish up indoors, which is often tempting if the weather or other conditions aren’t ideal–does a plein air painting retain its plein air status if it’s only 20 or 30 percent painted outdoors? How about 70 or 80 percent? No matter. If you do any of the work outdoors, Doherty says it counts.

Willingness to paint outdoors requires more than straightforward skills. It requires a real desire to be part of the place that you’re painting. It’s a mindset, an attitude, a combination of willingness to be flexible and a desire to capture the light and sensibility that you cannot quite find by referring to a photograph. That’s why the book begins not with a discussion of portable easels (that comes later), but with an insightful illustrated essay posing as Chapter 1: “Why Paint Outdoors?” He focuses on the mental game and also shows himself in the game, on the street, easel set up just beside a construction site so he can get just the right view, messy paint-covered sweatshirt and slight scowl and all. He ponders how much of the work needs to be done outdoors–if you finish up indoors, which is often tempting if the weather or other conditions aren’t ideal–does a plein air painting retain its plein air status if it’s only 20 or 30 percent painted outdoors? How about 70 or 80 percent? No matter. If you do any of the work outdoors, Doherty says it counts. As with most books of this sort, there are profiles of artists that the author admires, and lessons to be learned from each of them. There are also good large photographs of many types of plein air paintings, useful both for inspiration and also for studying technique. I like to see a good history chapter, too, in part because it’s fun to consider myself part of a longer tradition that once included John Constable, and Jean-Baptiste Corot, and best of all, painters who were part of the majestic Hudson River School.

As with most books of this sort, there are profiles of artists that the author admires, and lessons to be learned from each of them. There are also good large photographs of many types of plein air paintings, useful both for inspiration and also for studying technique. I like to see a good history chapter, too, in part because it’s fun to consider myself part of a longer tradition that once included John Constable, and Jean-Baptiste Corot, and best of all, painters who were part of the majestic Hudson River School.