The book is entitled “Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution,” and it’s written by a justice who retired in 2010. While it’s difficult to read the book without wondering why Justice Stevens didn’t magically bring about change while in office, I suspect that the article that I found in The Atlantic is unreasonably harsh in its pursuit of this argument. As in:

The retired Supreme Court justice would like to add five words to the Eight Amendment and do away with capital punishment in America. It’s a shame he didn’t vote that way during his 35 years on the Supreme Court.

Those words would have abolished the death penalty by constitutional amendment. The new eighth amendment might include the italicized words:

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments such as the death penalty inflicted.”

If you’re on death row, or if you care deeply about someone there, those five words make all the difference.

Similarly, Justice Stevens would add five words to the second amendment, forever clarifying the confusion about personal gun use as a constitutional right:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms when serving in the Militia shall not be infringed.”

So far, just ten words, and we end up with a vastly different free and criminal culture. And even if I am several months late in reviewing Stevens’ book and his ideas, I think every American citizen ought to be thinking about what we want from our amazingly effective governing document. Here’s another, this time about the practice of reorganizing election districts for political gain (“gerrymandering” dates back to 1812—it’s named for Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry). This is all new, and a bit dense:

Districts represented by members of Congress, or by members of any state legislative body, shall be compact and composed of contiguous territory. The state shall have the burden of justifying any departures from this requirement by reference to neutral criteria such as natural, political or demographic changes. The interest in enhancing or preserving the political power of the party in control of the state government is not such a neutral criterion.”

After reading this suggestion carefully, I’m left wondering how it would be enforced, and whether politicians would pay it any mind. Maybe it’s the wording, maybe its the concept, maybe its a matter of “giving up” on the political system. That last statement, about giving up, is the whole point. We’re giving up on a system that doesn’t work as it should, perhaps because it has been gerrymandered beyond reason or recognition. Maybe Stevens has the right idea or the wrong words.

After reading this suggestion carefully, I’m left wondering how it would be enforced, and whether politicians would pay it any mind. Maybe it’s the wording, maybe its the concept, maybe its a matter of “giving up” on the political system. That last statement, about giving up, is the whole point. We’re giving up on a system that doesn’t work as it should, perhaps because it has been gerrymandered beyond reason or recognition. Maybe Stevens has the right idea or the wrong words.

Moving on to campaign finance…

Neither the First Amendment nor any other provision of this Constitution shall be construed to prohibit the Congress or any state from imposing reasonable limits on the amount of money that candidates for public office, or their supporters, may spend in election campaigns.

New words, good idea, but we’re caught in the non-virtuous circle of politicians making rules for themselves and other politicians. Interesting article in The New York Times focuses on this issue, and on Justice Stevens’ book. (And yes, Stevens dissented on the Citizens United decision.)

One of the reasons I am writing this article is selfish. I want a good clean list of the former justice’s ideas, and I couldn’t find one on the internet, so I wrote it myself.

The last two are more complicated and require a deeper understanding of Constitutional law and government action. He would like to add “and other public officials” to

All debts contracted and engagements entered into, before the adoption of this Constitution, shall be as valid against the United States under this Constitution, as under the Confederation.

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, and other public officials, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.

The final item is entitled Sovereign Immunity, and it’s more difficult to understand than the others. His suggested amendment:

Neither the Tenth Amendment, the Eleventh Amendment, nor any other provision of this Constitution, shall be construed to provide any state, state agency or state officer with an immunity from liability for violating any act of Congress, or any provision of this Constitution.”

O n the surface, this is clear, but it’s made more clear by the Justice’s twenty pages of commentary. In that endeavor, I’m sometimes a fan—his historical and contextual understanding is, well, supreme, but his ability to connect with a broad audience sometimes falters. The history becomes too complicated, the issues too tangled, nods to other justices sometimes adding complexity. On the other hand, we’re talking about a book that’s less than 150 pages and contains a whole lot of provocative, clearly presented material.

n the surface, this is clear, but it’s made more clear by the Justice’s twenty pages of commentary. In that endeavor, I’m sometimes a fan—his historical and contextual understanding is, well, supreme, but his ability to connect with a broad audience sometimes falters. The history becomes too complicated, the issues too tangled, nods to other justices sometimes adding complexity. On the other hand, we’re talking about a book that’s less than 150 pages and contains a whole lot of provocative, clearly presented material.

Wouldn’t it be interesting if every Supreme Court justice wrote a similar book?

With digital publishing, the rules don’t apply—and for so many reasons. For example, publishers need not limit the number of titles they publish for any practical reason—there is no scarcity of shelf space. (They may limit releases due to marketing considerations, but that’s another story altogether.) Of course, bookstores are helpful parts of the marketing and distribution system, but they are no longer mandatory—Amazon ships just about any book, next day.

With digital publishing, the rules don’t apply—and for so many reasons. For example, publishers need not limit the number of titles they publish for any practical reason—there is no scarcity of shelf space. (They may limit releases due to marketing considerations, but that’s another story altogether.) Of course, bookstores are helpful parts of the marketing and distribution system, but they are no longer mandatory—Amazon ships just about any book, next day. Walter Isaacson is one of the smarter people in the media industry. As a keynote speaker for this past week’s Digital Book World conference, he talked about the limitations of his most recent book,

Walter Isaacson is one of the smarter people in the media industry. As a keynote speaker for this past week’s Digital Book World conference, he talked about the limitations of his most recent book,  For example, maybe a digital book is not a book at all, but a kind of game. Scholastic, a leader in a teen (YA, or Young Adult) fiction publishes a new book in each series at four-month intervals. The publisher wants to maintain a relationship with the reader, and the reader wants to continue to connect with the author and the characters. So what’s in-between, what happens during those (empty) months between reading one book and the publication of the next one in the series? And at what point does the experience (a game, a social community) overtake the book? NEVER! — or so says a Scholastic multimedia producer working in that interstitial space. The book is the thing; everything else is secondary. In fact, I don’t believe him—I think that may be true for some books, but the clever souls at Scholastic are very likely to come up with a compelling between-the-books experience that eventually overshadows the book itself.

For example, maybe a digital book is not a book at all, but a kind of game. Scholastic, a leader in a teen (YA, or Young Adult) fiction publishes a new book in each series at four-month intervals. The publisher wants to maintain a relationship with the reader, and the reader wants to continue to connect with the author and the characters. So what’s in-between, what happens during those (empty) months between reading one book and the publication of the next one in the series? And at what point does the experience (a game, a social community) overtake the book? NEVER! — or so says a Scholastic multimedia producer working in that interstitial space. The book is the thing; everything else is secondary. In fact, I don’t believe him—I think that may be true for some books, but the clever souls at Scholastic are very likely to come up with a compelling between-the-books experience that eventually overshadows the book itself.

was an extraordinarily clear thinker about things that matter. That clarity, and her passion, and her just-plain-good writing are the reasons why I will spend the winter reading every one of about fifty articles and essays in a book that her daughter Nona put together. It’s called “The Essential Ellen Willis.” I’m guessing you won’t find it in many bookstores despite the best efforts of the University of Minnesota Press, but it’s certainly available online. For someone who enjoys smart writing with more than a small dose of social conscience, it’s an ideal holiday choice.

was an extraordinarily clear thinker about things that matter. That clarity, and her passion, and her just-plain-good writing are the reasons why I will spend the winter reading every one of about fifty articles and essays in a book that her daughter Nona put together. It’s called “The Essential Ellen Willis.” I’m guessing you won’t find it in many bookstores despite the best efforts of the University of Minnesota Press, but it’s certainly available online. For someone who enjoys smart writing with more than a small dose of social conscience, it’s an ideal holiday choice.

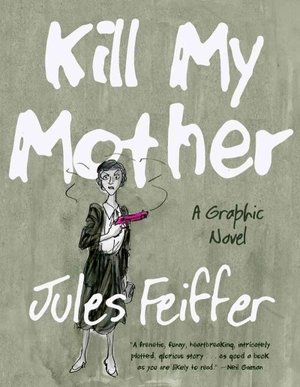

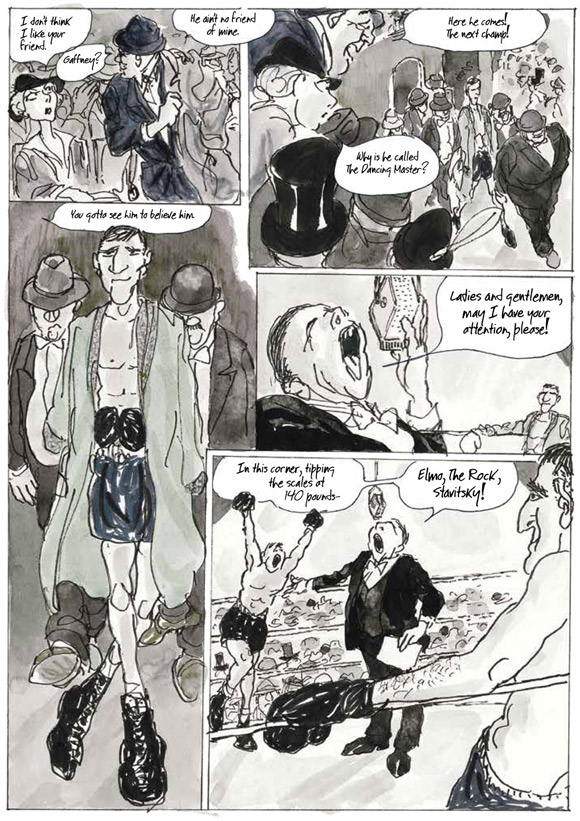

Okay, more about Jules before begin. Actually, you get a fair sense of him from his 2008 cartoon for NYC’s Village Voice. I found it on Wikipedia. He won a Pulitzer Prize for political cartooning, was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Writer’s Guild of America, and he’s got his place in the Comic Book Hall of Fame. And now, he’s got this new book.

Okay, more about Jules before begin. Actually, you get a fair sense of him from his 2008 cartoon for NYC’s Village Voice. I found it on Wikipedia. He won a Pulitzer Prize for political cartooning, was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Writer’s Guild of America, and he’s got his place in the Comic Book Hall of Fame. And now, he’s got this new book. In theory, it’s the book that drives the story, but in practice, here, it’s the pictures. Actually, it’s the whole page, the whole well-designed, elegantly organized duotone watercolors and pen-and-ink that feel so dark, so thick with intrigue. Most of the book is rendered in sepia—not the old tones of photographs, but lively, contrasty, vaguely seedy renditions of what otherwise might have been black. The accent is usually a very pale green, the color of a Hollywood swimming pool on page, a cadaver on the next.

In theory, it’s the book that drives the story, but in practice, here, it’s the pictures. Actually, it’s the whole page, the whole well-designed, elegantly organized duotone watercolors and pen-and-ink that feel so dark, so thick with intrigue. Most of the book is rendered in sepia—not the old tones of photographs, but lively, contrasty, vaguely seedy renditions of what otherwise might have been black. The accent is usually a very pale green, the color of a Hollywood swimming pool on page, a cadaver on the next.

Freediving is “the most direct and intimate way to connect with the ocean.” During a three-minute freedive, “the (human) body bears only a passing resemblance to its terrestrial form and function. The ocean changes us physically, and psychically.” Unfortunately, “sometimes you don’t make it back alive.” Those words were written by James Nestor in his new book, “Deep: Freediving, Renegade Science and What the Ocean Tells Us about Ourselves.” It’s one of the best books I’ve read this year, an introduction to a part of our world that is unfamiliar to nearly everyone on the planet, and an adventure story, too.

Freediving is “the most direct and intimate way to connect with the ocean.” During a three-minute freedive, “the (human) body bears only a passing resemblance to its terrestrial form and function. The ocean changes us physically, and psychically.” Unfortunately, “sometimes you don’t make it back alive.” Those words were written by James Nestor in his new book, “Deep: Freediving, Renegade Science and What the Ocean Tells Us about Ourselves.” It’s one of the best books I’ve read this year, an introduction to a part of our world that is unfamiliar to nearly everyone on the planet, and an adventure story, too.