This article was published in Education Week in January, 2009. I think it’s terrific. The author is Marion Brady, “a retired high school teacher, college professor, and textbook author who writes frequently on education. He lives in Cocoa, Fla.”

Driving the rural roads of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, I’ve occasionally been fortunate enough to be blocked by sheep being moved from one pasture to another.

Driving the rural roads of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, I’ve occasionally been fortunate enough to be blocked by sheep being moved from one pasture to another.

I say “fortunate” because I’ve gotten to watch an impressive performance by a dog—a border collie.

And what a performance! A single, midsize dog herding two or three hundred sheep, keeping them moving in the right direction, rounding up strays, knowing how to intimidate but not cause panic, funneling them all through a gate, and obviously enjoying the challenge.

Why a border collie? Why not an Airedale or Zuchon, or another of about 400 breeds listed on the Internet?

Because, among those for whom herding sheep is serious business, there’s general agreement that border collies are better than any other dog at doing what needs to be done. They have “the knack.” That knack is so important, those who care most about border collies even oppose their being entered in dog shows. They’re certain that would lead to border collies being bred to look good, and looking good isn’t the point. What counts is talent, interest, innate ability, performance.

Other breeds are no less impressive in other ways. If you’re lost in a snowstorm in the Alps, you don’t need a border collie. You need a big, strong dog with a good nose, lots of fur, wide feet, and a great sense of direction for returning with help. You need a Saint Bernard.

If varmints are sneaking into your henhouse, killing your chickens, and escaping down a little hole in a nearby field, you don’t need a border collie or a Saint Bernard. You need a fox terrier.

Want to sniff luggage for bombs? Chase felons? Stand guard duty? Retrieve downed game birds? Guide the blind? Detect certain diseases? Locate earthquake survivors? Entertain audiences? Play nice with little kids? Go for help if Little Nell falls down a well? With training, dogs can do those jobs well.

So, let’s set performance standards and train all dogs to meet them. All 400 breeds. Leave no dog behind. Two-hundred-pound mastiffs may have a little trouble with the chase-the-fox-into-the-little-hole standard, and Chihuahuas will probably have difficulty with the tackle-the-felon-and-pin-him-to-the-ground standard. But, hey, standards are standards! No excuses! No giving in to the soft bigotry of low expectations. Hold dogs accountable.

Here’s a question: Why are one-size-fits-all performance standards inappropriate to the point of silliness when applied to dogs, but accepted without question when applied to kids? If someone tried to set up a national program to teach every dog to do everything that various breeds are able to do, the Humane Society and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals would have them in court in a New York minute. But when authorities mandate one-size-fits-all performance standards for kids, and the standards aren’t met, it’s the kids and teachers, not the standards, that get blamed.

Here’s a question: Why are one-size-fits-all performance standards inappropriate to the point of silliness when applied to dogs, but accepted without question when applied to kids? If someone tried to set up a national program to teach every dog to do everything that various breeds are able to do, the Humane Society and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals would have them in court in a New York minute. But when authorities mandate one-size-fits-all performance standards for kids, and the standards aren’t met, it’s the kids and teachers, not the standards, that get blamed.

Consider, for example, what’s happening in math “reform.” School systems across the country are upping both the number of required courses and their level of difficulty. Why? Is it because math teaches transferable thinking skills? There’s no research supporting that contention. Is it because advanced math is required for college work? Where’s the evidence that colleges have a clear grasp of America’s educational challenge and therefore should be leading the education parade? Is it because most adults make routine use of higher math? No. Is it because American industry is begging for more mathematicians? Not according to statistics on available job opportunities. Is it because math has played an important role in America’s technological achievements, and if we’re to continue to be pre-eminent, a full range of math courses needs to be taught?

Bingo! And true. But how much sense does it make to run every kid in America through the same math regimen, when only a small percentage has enough mathematical ability to make productive use of it? How much sense does it make to put a math whiz in an Algebra 2 classroom with 25 or 30 aspiring lawyers, dancers, automatic-transmission specialists, social workers, surgeons, artists, hairdressers, language teachers? How much sense does it make to put hundreds of thousands of kids on the street because they can’t jump through a particular math hoop?

Some suggestions:

One: Stop fixating on the American economy. Trying to shape kids to fit the needs of business and industry rather than the other way around is immoral.

Two: Stop massive, standardized testing. For a fraction of the cost of high-stakes subject-matter tests, every kid’s strengths and weaknesses can be identified using inexpensive inventories of interests, abilities, and learning styles.

Three: Eliminate grade levels. Start with where kids are, help them go as far as they can go as fast as they can go, then give them a paper describing what they can do, or a Web site where they can do it for themselves.

Four: When kids are ready for work, push responsibility for teaching specialized skills and knowledge onto users of those skills and knowledge—employers. Occupation-related instruction such as that now being offered in magnet schools will never keep up with the variety of skills needed or their rates of change. Apprenticeships and intern arrangements will go a long way toward smoothing the transition into responsible adulthood.

Five: Abandon the assumption that spending the day “covering the material” in a random mix of five or six subjects educates well. Only one course of study is absolutely essential. Societal cohesion and effective functioning require participation in a broad conversation about values, beliefs, and patterns of action, their origins, and their probable and possible future consequences. The young need to engage in that conversation, and a single, comprehensive, systemically integrated course of study could prepare them for it. It should be the only required course.

Six: Limiting required study to a single course would result in an explosion of educational options (and save a lot of money). We say we respect individual differences, say we value initiative, spontaneity, and creativity, say we admire the independent thinker, say every person should be helped to realize her or his full potential, say the young need to be introduced to the real world—then we spend a half-trillion dollars a year on a system of education at odds with our rhetoric. Aligning the institution with our core values would give it the legitimacy and generate the excitement it now lacks.

Alternatively, we can continue on our present course. For almost 20 years, “reform” has been driven by the assumption that “the system”—the math, science, language arts, and social studies curriculum in near-universal use in America’s schools and colleges since 1892—is sound, from which it follows that poor performance must be the fault of the teachers and kids. This, of course, calls for tough love—standards, accountability, raised bars, rigor, competitive challenges, public shaming, pay for performance, penalties for nonperformance.

Wrong diagnosis, so wrong cure. The problem isn’t the kids and the teachers; it’s the system. More than a century of failed attempts to drive square pegs into round holes suggests it’s past time to stop treating human variability as a problem rather than as an evolutionary triumph, and begin making the most of it.

Marion Brady is a retired high school teacher, college professor, and textbook author who writes frequently on education. He lives in Cocoa, Fla.

Geri Allen is one of those extraordinary jazz musicians whose influence runs wide and deep, but somehow, has not become as well-known as it ought to be. She’s a pianist with a resume that begins with a serious educational foundation: a master’s degree in ethnomusicology that has served her well (easy for me to see this because I’m approaching her life’s work some 35 years into a very good story). Her professional work begins with Mary Wilson and the Supremes in the early 1980s, and Brooklyn’s

Geri Allen is one of those extraordinary jazz musicians whose influence runs wide and deep, but somehow, has not become as well-known as it ought to be. She’s a pianist with a resume that begins with a serious educational foundation: a master’s degree in ethnomusicology that has served her well (easy for me to see this because I’m approaching her life’s work some 35 years into a very good story). Her professional work begins with Mary Wilson and the Supremes in the early 1980s, and Brooklyn’s  The awards began to roll in. Allen was in and out of the remaining avant-garde, which sounds much less radical now than in 1996 when she recorded “Hidden Man” with Ornette Coleman’s Sound Museum. In fact, by 1999, she was sounding very comfortable in a commercial setting, recording her popular CD, The Gathering, with Wallace Roney on flugelhorn and trumpet, Robin Eubanks on trombone, Buster Williams on bass, and Lenny White on drums, and others whose names are well-known from mainstream jazz records. A 2010 record, “Flying Toward the Sound,” made it to the top of many critic’s best-of-the-year lists.

The awards began to roll in. Allen was in and out of the remaining avant-garde, which sounds much less radical now than in 1996 when she recorded “Hidden Man” with Ornette Coleman’s Sound Museum. In fact, by 1999, she was sounding very comfortable in a commercial setting, recording her popular CD, The Gathering, with Wallace Roney on flugelhorn and trumpet, Robin Eubanks on trombone, Buster Williams on bass, and Lenny White on drums, and others whose names are well-known from mainstream jazz records. A 2010 record, “Flying Toward the Sound,” made it to the top of many critic’s best-of-the-year lists.

Geri Allen has been one of those artists that I’ve wanted to know more about. Now that I’ve written this article, now that I’ve done some concentrated listening, I’m realizing that I am just beginning to understand what she’s all about. The latest album is elegant and wonderful, soulful and reflective, sophisticated and consistently interesting, but my collection is now woefully incomplete. I have listened to the two predecessors in the trilogy, but I want them for my very own. The same is true for the work she did with Paul Motian and Charlie Haden, and for the work she did in 2010 with her group, Timeline.

Geri Allen has been one of those artists that I’ve wanted to know more about. Now that I’ve written this article, now that I’ve done some concentrated listening, I’m realizing that I am just beginning to understand what she’s all about. The latest album is elegant and wonderful, soulful and reflective, sophisticated and consistently interesting, but my collection is now woefully incomplete. I have listened to the two predecessors in the trilogy, but I want them for my very own. The same is true for the work she did with Paul Motian and Charlie Haden, and for the work she did in 2010 with her group, Timeline.

The next character in what turned out to a fascinating Saturday night at the Glimmerglass Festival just north of Cooperstown NY is Tobias Picker. If you don’t know the name, you should. “An American Tragedy” is his fourth opera (and one of several he has written with Gene Scheer’s libretto—you may know

The next character in what turned out to a fascinating Saturday night at the Glimmerglass Festival just north of Cooperstown NY is Tobias Picker. If you don’t know the name, you should. “An American Tragedy” is his fourth opera (and one of several he has written with Gene Scheer’s libretto—you may know

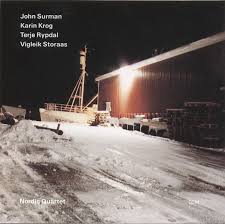

In 1969, most people, even those who were following the progression from jazz to fusion, hadn’t yet heard the work of a British guitar player named John McLaughlin. That was the year that he recorded his first album, “Extrapolation.” At the time, it was wildly experimental, but as I listen to it in the background while writing this article, it’s really delightful, gentle, meditative, not at all explosive. McLaughlin is a gifted guitar player and composer. He shares the stage with an another young British musician, a man who plays the somewhat unusual combination of soprano and baritone sax. His name is John Surman. At the time, Surman was already recording on his own for the

In 1969, most people, even those who were following the progression from jazz to fusion, hadn’t yet heard the work of a British guitar player named John McLaughlin. That was the year that he recorded his first album, “Extrapolation.” At the time, it was wildly experimental, but as I listen to it in the background while writing this article, it’s really delightful, gentle, meditative, not at all explosive. McLaughlin is a gifted guitar player and composer. He shares the stage with an another young British musician, a man who plays the somewhat unusual combination of soprano and baritone sax. His name is John Surman. At the time, Surman was already recording on his own for the  Traces, there is a deep female voice whose sound more closely resembles an instrument than an upfront vocalist—and she’s singing phrases that feel more like poetry than lyrics. She was not credited as a singer, but instead, as “voice.” Her name is Karin Krog.

Traces, there is a deep female voice whose sound more closely resembles an instrument than an upfront vocalist—and she’s singing phrases that feel more like poetry than lyrics. She was not credited as a singer, but instead, as “voice.” Her name is Karin Krog. Earlier this year, late at night, I decided to do a Google Search on

Earlier this year, late at night, I decided to do a Google Search on

Of the three CDs, the most interesting is also the most experimental, a cycle of songs originally composed for a 2010 jazz festival. It’s called “Songs About This and That,” and I like it because it recalls my earlier interest in their exuberant experimental side, but places it in a more artful, more carefully arranged setting. There is a sense of open time and space to explore, to allow for long lines, an ease with the maturation of Karin’s voice. On this CD, I think my favorite track may be “Cherry Tree Song” because the poetic lyrics wind so gracefully around John’s baritone sax and bass clarinet, a warm combination of electric guitar, vibraphone, and John’s bass recorder. In fact, I jotted down some other favorite tracks, and found the list was too long to manage, but I will mention the vibe solo that begins “Moonlight Song” and Karin’s waking-up voice, looking backward on memory. Wrapping up an article I’ve so enjoyed writing, I happened to notice that Karin’s credit on this CD is what it was so many years before, not “vocals” but simply, “voice.”

Of the three CDs, the most interesting is also the most experimental, a cycle of songs originally composed for a 2010 jazz festival. It’s called “Songs About This and That,” and I like it because it recalls my earlier interest in their exuberant experimental side, but places it in a more artful, more carefully arranged setting. There is a sense of open time and space to explore, to allow for long lines, an ease with the maturation of Karin’s voice. On this CD, I think my favorite track may be “Cherry Tree Song” because the poetic lyrics wind so gracefully around John’s baritone sax and bass clarinet, a warm combination of electric guitar, vibraphone, and John’s bass recorder. In fact, I jotted down some other favorite tracks, and found the list was too long to manage, but I will mention the vibe solo that begins “Moonlight Song” and Karin’s waking-up voice, looking backward on memory. Wrapping up an article I’ve so enjoyed writing, I happened to notice that Karin’s credit on this CD is what it was so many years before, not “vocals” but simply, “voice.”