Douglas Engelbart passed away recently. His name may be unfamiliar. His work is not.

Engelbart was an engineer who invented, among other things, your computer’s mouse, and, by extension, his work made the trackpad possible as well. In his conception, the mouse was a box with several buttons on top and the ability to move what he called an on-screen “tracking point.” In 1968, this idea was radically new. I encourage you to watch Mr. Engelbart in action by screening the video, now widely known as “The Mother of All Demos” in the hardware and software community because of all that he presents. Among the innovations: a video projection system, hyperlinking, WSYWIG (what you see is what you get–the basis of word processing and more), teleconferencing and more. He’s clearly having a wonderful time with this demo, very proud of what has been accomplished, keen on the possibilities for a future that we all now accept as routine.

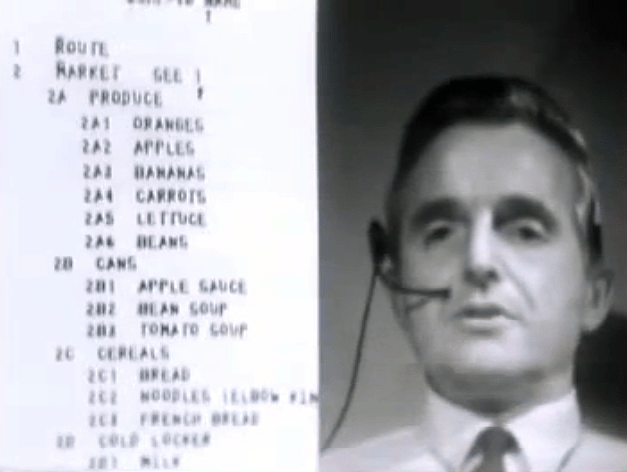

Douglas Engelbart in “The Mother of All Demos,” as this hour-plus presentation has come to be known.

You’re actually able to point at the information you’re trying to retrieve, and then move it

Intrigued? Here’s a look at the input station. On the right is the mouse; at the center is the keyboard; and on the left is an interesting five-switch input device that allows quick typing by holding down each of the five keys in various combinations to enter characters without using the keyboard (some of these ideas were later revised for current trackpad use).

A very early version of a computer mouse as explained by its inventor, Douglas Engelbart.

Still unsure about whether this video is worth your time? Think of it as a TED Talk, circa 1968.

Hungry for more? Watch this video on the Doug Engelbart Institute website. Here, he speaks about collective learning and the need for a central knowledge repository. The video was recorded in 1998, shortly after the internet first became popular. His vision recalls the era when we all dreamed about what the internet might someday be.

The complexity and urgency of the problems faced by us earth-bound humans are increasing much faster than are our aggregate capabilities for understanding and coping with them. This is a very serious problem; and there are strategic actions we can take, collectively. – Doug Engelbart