“So I swallowed hard, gulped, and said ‘Roll camera… action!’ He (Hitchcock) sat back in the chair, encouraging me, benignly nodding his head periodically, and giving me the ‘roll’ signal as I set up each shot, matching them to the storyboard.”

“So I swallowed hard, gulped, and said ‘Roll camera… action!’ He (Hitchcock) sat back in the chair, encouraging me, benignly nodding his head periodically, and giving me the ‘roll’ signal as I set up each shot, matching them to the storyboard.”

The film was Psycho. The scene was storyboarded, and directed, by Saul Bass. Hitchcock trusted him. That was unusual. But then, Saul Bass was a pretty unusual guy.

The story, told in magnificent coffee table book splendor, begins in New York City, then quickly shifts to Los Angeles, where Saul begins to design movie advertisements, then movie posters, then movie campaigns. His modernist approach defined the era (seems like an overstatement, but it’s not). The films are iconic, but by today’s terms, old news: The Man With the Golden Arm and Exodus, for example, but Some Like It Hot and Around the World in 80 Days, and It’s a Mad, Mad World remain popular. And surely, you’ve seen Bass’s title work on the Hitchcock films, North by Northwest, Vertigo, and Psycho. Remember the cool animated opening sequence for the original Ocean’s 11? That’s Bass, too. Oh, one more: the entire opening sequence of West Side Story, where line art becomes aerial photography. And another; Walk on the Wild Side, whose mysterious cat eyes were later used for the famous Broadway musical. After the 1960s, his contributions to film begin to slow down (reasons below), but he still manages to design the opening sequences for Goodfellas and Cape Fear for Martin Scorsese, who writes the intro to this hefty book.

Anatomy of a Murder: one of the best Saul Bass movie posters.

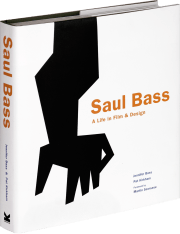

Page after page, over nearly 400 pages, the astonishing Saul Bass: A Life in Film & Design by Jennifer Bass and Pat Kirkham, provides an education in visual communication. This is high level design, magnificently executed, and, in these pages, dissected with intelligent prose and step-by-step storyboards.

But wait, there’s more.

He found…that while film clients shared a common vocabulary and were familiar with thinking visually, for the most part, this was not the case with corporate clients. For the majority, this was their first experience working in the visual realm.”

Deep down, Bass was an extraordinarily gifted visual thinker… and quite the showman. His dash of show business played well among corporate executives, and, apparently, his presentation of new logos and corporate identities was quite memorable.

You know his work. It’s foolish for me to write much about it. The pictures tell the story better than words. So, as you think serious about buying this book–it should be a part of every creative professional’s library, enjoy the extra range of Saul Bass’s corporate work. Followed, briefly, by some of his equally extraordinary posters and related designs.

Logos designed by Saul Bass. From top left: Bell System, AT&T, General Foods, United Airlines, Avery International, Continental Airlines, Celanese, United Way, Rockwell International, Minolta, Girl Scouts of the USA, Lawry’s Foods, Quaker Oats, Kleenex, Frontier Airlines, Dixie, Warner Books and Warner Communications, Fuller Paints. (From Wikipedia)

This tribute site includes some of Bass’s posters, with an emphasis on his movie work.

And here’s the info about the book. Along with one last pitch from me: few creative professionals have enjoyed the breadth and depth of Mr. Bass’s extraordinary career. Just looking at the pictures will move you from interest to a true desire to do excellent creative work. Taking the time to read the text, and refer to it from time to time, makes a kind of magic possible. This is a book worth owning. And, if the spirit moves you, a gift that a friend or family measure will enjoy for years to come. Seriously.