Share this with:

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

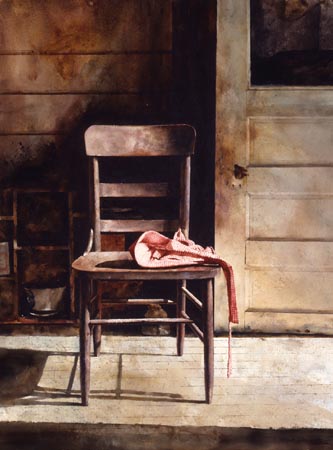

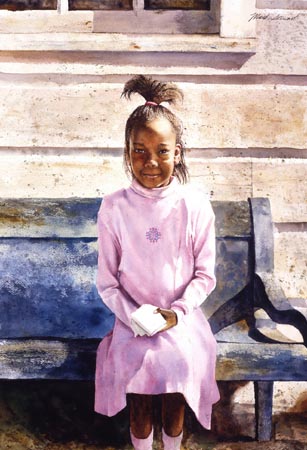

Every once in a while, I’ll find an artist on the web whose work I truly admire. I recently stumbled upon a Texas watercolorist named Mark Stewart, and I thought you might enjoy seeing some of his work. Of course, there’s no reason why you should read any of what I have to say… just go directly to his

Every once in a while, I’ll find an artist on the web whose work I truly admire. I recently stumbled upon a Texas watercolorist named Mark Stewart, and I thought you might enjoy seeing some of his work. Of course, there’s no reason why you should read any of what I have to say… just go directly to his