When times were rotten, New York City was nicknamed “Fun City”–a dark commentary on the nightmare of garbage strikes, teacher walkouts, and a financial meltdown. Even in its most hopeless years, New York’s challenges pale in comparison with York, a far smaller and far older place that provided Fun City with its formal name.

The fun begins in York about 10,000 years ago. The Romans showed up about 2,000 years ago–certainly by 71 AD–and you can walk the Roman wall that once guarded the city today. It’s a very pleasant walk on a summer’s day, complete with engaging city views, small cafes, and pretty places to take selfies (admittedly, only parts are original; some are newer, circa 1200 or so, and others, newer still circa 1800-1900). By 875 AD, York was a Viking stronghold–a very large cache of Viking goodies from as far off as Afghanistan can now be found in the British Museum, the result of a York excavation for a new shopping area. Here, we find the roots of York’s current name–the Vikings called their kingdom Jorvik, since corrupted to provide both York and New York their Danish-rooted names.

The fun begins in York about 10,000 years ago. The Romans showed up about 2,000 years ago–certainly by 71 AD–and you can walk the Roman wall that once guarded the city today. It’s a very pleasant walk on a summer’s day, complete with engaging city views, small cafes, and pretty places to take selfies (admittedly, only parts are original; some are newer, circa 1200 or so, and others, newer still circa 1800-1900). By 875 AD, York was a Viking stronghold–a very large cache of Viking goodies from as far off as Afghanistan can now be found in the British Museum, the result of a York excavation for a new shopping area. Here, we find the roots of York’s current name–the Vikings called their kingdom Jorvik, since corrupted to provide both York and New York their Danish-rooted names.

After the Vikings, York weathered a less distinguished period. One of the worst episodes: the burning of Jews supposedly under government protection in the 1100s–an old castle is still on the site. By 1300, York was both an important government and trading center for England, and remained so until the 1500s. You can walk the streets and see medieval buildings–not unlike walking the world of Harry Potter (celebrated by several souvenir shops).

After the Vikings, York weathered a less distinguished period. One of the worst episodes: the burning of Jews supposedly under government protection in the 1100s–an old castle is still on the site. By 1300, York was both an important government and trading center for England, and remained so until the 1500s. You can walk the streets and see medieval buildings–not unlike walking the world of Harry Potter (celebrated by several souvenir shops).

All of this (except Potter, of course) took place well before anybody even considered the idea of New Amsterdam (founded 1625), or New York (renamed 1664). To celebrate the old days, I visited York with the sole expectation of attending a really excellent Early Music Festival, now held annually each July.

This year’s featured players included The Sixteen (arguably the finest early music vocal group in the world today), and the majestic Gallicantus (a vocal group) in concert with the Rose Consort of Viols (an instrumental group). The latter two performed in an old parish church called St Michael le Belfrey Church (circa 1525) with marvelous acoustics and an equally appealing visual character. The music of Gallicantus celebrated Thomas Tomkins (1572-1656) and William Lawes (1602-1643), but I was most taken by a contemporary work in the old style by Judith Bingham (b. 1952) called “A Requiem for Mr. William Lawes.” Like so much early music (the term more or less refers to music preceding Bach, Vivaldi, etc.), this is vocal music that reaches directly into the soul, with astonishing countertenors (here David Allsopp and Mark Chambers) singing music that would later become the job of women. The sheer joy of listening to these wonderful musicians would have been sufficient, but the addition of a viol consort–not violins, not violas, as the musicians explained in a private interview, but viols that come up through a different strand of music history and were reproduced from paintings and other scant visual history).

Equally impressive: a Saturday afternoon concert called Revolting Women! featuring music composed by what was likely a small population of female composers from the era. The best was composed by a woman now recalled only by her pseudonym, Mrs Philharmonica, presumably from about 1715. Other names, bound to be unfamiliar, but worth researching, include Isabella Leonarda (1665-1729) and Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665-1729). Their work was much enriched by the formidable professor, historian and superior violinist, Lucy Russell, whose name may be familiar from her work with the extraordinary Fitzwilliam String Quarter (which is known for more traditional classical repertoire).

Much as I adore good concerts in old churches, a warm summer day in York offers far too much fun to remain indoors for long. I was disappointed because my schedule would not allow me to attend Richard III at, of all things, a 1000-seat pop-up Shakespeare Rose Theater in the center of town (complete with a shopping and food arcade contemporary to the era). I also had limited time to fully explore Bloom!, a flower festival staged at what seemed to be a hundred places around town. Good used bookstores captured my attention, along with long walks along the river, and the inevitable Betty’s, a 1919 tea shop with wonderful food and spectacular pastries to enjoy along with fine tea service. (In fact, I escaped to nearby Harrogate, where I enjoyed both a lunch at Betty’s and also a walk around the RHS (Royal Horticultural Society) Harlow Carr gardens, an easy local train ride from classic York train station). Given more time, I would have explored the interior of York Minster, a large and delightfully old cathedral as well–but the lines were long, the schedule a bit restrictive for my 48-hour visit. Including the nearby countryside (moors, Jane Austen, etc.), I would certainly allow at least 72 hours to explore the area, and you’d likely find plenty to do for even four or five days in the York and Yorkshire area (mostly easily reached by train, certainly easily reached by car or even day bus tours).

What have I missed? The quiet pub where the World Cup semi-final victory for England was celebrated in a most dignified manner. The streets outside where everyone’s cheeks (probably both kinds) were painted with tiny English soccer flags, where people sang, loudly with with tremendous dancing exuberance, about how the Cup was “coming home.” Nearly every pub in town was pounding with energy and music–including, inexplicably, “Take Me Home Country Roads” and other boisterous (?) John Denver tunes to which every Brit seemed to know every word; the medley ended with the British (?) classic, “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” All great fun!

What have I missed? The quiet pub where the World Cup semi-final victory for England was celebrated in a most dignified manner. The streets outside where everyone’s cheeks (probably both kinds) were painted with tiny English soccer flags, where people sang, loudly with with tremendous dancing exuberance, about how the Cup was “coming home.” Nearly every pub in town was pounding with energy and music–including, inexplicably, “Take Me Home Country Roads” and other boisterous (?) John Denver tunes to which every Brit seemed to know every word; the medley ended with the British (?) classic, “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” All great fun!

Food: very nice classy seafood to be found in Loch Fyne, which is not far from the old church headquarters of National Centre for Early Music (where many concerts are staged throughout the year). Just outside the city walls and down a few blocks, I stayed at the Mount Royal, a good old-style British hotel, perhaps more like an expanded inn, with a very nice outdoor garden and very comfortable rooms with ample space to stretch out. Good respite, very accommodating staff, and lovely to be able to take breakfast (and other meals) outside at leisure before re-entering, well, what turned out to be fun city in the truest sense of the words.

Do take the time to visit York. It’s just a few hours from London. It’s an easy train ride from Manchester, Liverpool and other cities in England, all worth visiting. And the next time I manage a visit, I want to wander the countryside (note to self: allow lots more time to explore this part of the world because it is beautiful, richly historic, and crazy fun).

For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain,

For many years, the very best place on planet earth to shop for LPs (or, if you prefer, records), was Yonge Street in Toronto, Canada. As it happens, Yonge (pronounced “Young”) is one of the world’s longest streets, but that’s not why I visited as often as possible. There were two very large record stores on Yonge Street around Gould and Dundas Streets — A&A Records, and my multi-floor, multi-building favorite, the flagship store for what became a 140-store chain,

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

The process begins with the master tape, but the metal stamper used to make the vinyl record is already second generation (“grandson” to the master tape), and the first pressing of the consumer record is the third generation, or great grandson. To James’s ears, you’re hearing less than half of the sound, and sound quality, that you would hear on the master tape. And that’s with a first pressing, under ideal conditions, listening to product from a record label that took the time and spent the money to get things right. Of course, most record companies don’t, or did not, lavish so much attention, which is why even the best used vinyl recordings from the golden age (say, 1960s and early 1970s before the oil crisis) don’t score much more than a 40 percent.

d the corner from the museum is The Four Way Restaurant, where Stax musicians, producers and engineers used to eat, and where I shared a table with a preacher who was touring the South, speaking about how Wal-Mart was destroying the local economy. Fried chicken, fried fish, side dishes of greens and yams. Preacher told me he would be heading next to Clarksdale, then on to Cleveland (Mississippi) and Indianola, just a few hours south. Next morning, I decided to skip a few speeches at a trade show and head for Clarksdale, figuring I’d be back just after lunch. I guess I didn’t anticipate driving down Highway 61, or waiting on Aunt Sarah to do her daily deliveries before serving lunch in what turned out to be one of the few places to buy lunch in the once-vibrant small city of Clarksdale. And if it wasn’t for my visit with Roger Stolle in the

d the corner from the museum is The Four Way Restaurant, where Stax musicians, producers and engineers used to eat, and where I shared a table with a preacher who was touring the South, speaking about how Wal-Mart was destroying the local economy. Fried chicken, fried fish, side dishes of greens and yams. Preacher told me he would be heading next to Clarksdale, then on to Cleveland (Mississippi) and Indianola, just a few hours south. Next morning, I decided to skip a few speeches at a trade show and head for Clarksdale, figuring I’d be back just after lunch. I guess I didn’t anticipate driving down Highway 61, or waiting on Aunt Sarah to do her daily deliveries before serving lunch in what turned out to be one of the few places to buy lunch in the once-vibrant small city of Clarksdale. And if it wasn’t for my visit with Roger Stolle in the

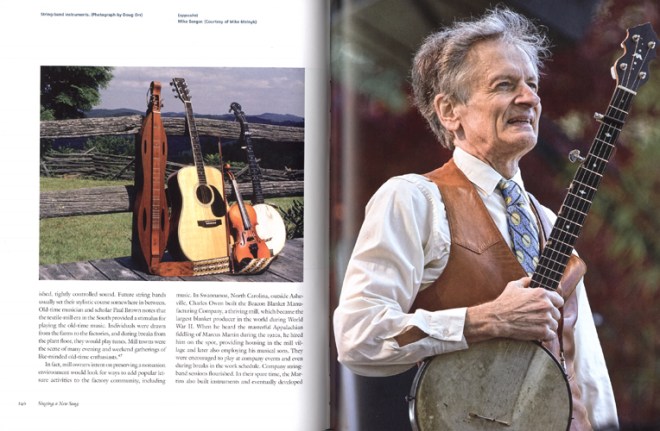

Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

Every once in a while, I’ll catch an episode of The Thistle & The Shamrock on a public radio station. Seems to me, the show has been on forever, but I’ve never thought much about the program’s title. Of course, it refers to music from Scotland and from Ireland, but that’s a very small part of the story that its host / producer tells in her new book, Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. (From the start, I should point out that this is a fabulous book, a work deserving of all kinds of awards and many quiet hours of reading accompanied by many more spent listening, preferably to live music.) In fact, it’s not just Ms. Ritchie’s book: storytelling and scholarly research duties are shared by an equally talented music lover, Doug Orr, whose Swannanoa Gathering is, among many good things, the place where the idea of the Carolina Chocolate Drops took shape: “they have helped revive an old African American banjo tradition that was fast disappearing.”

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

The authors have done just that, and so, in their way, have Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others whose names may be less familiar. But the authors have accomplished more. They’ve managed to weave a very complicated story together, a saga of migration and evolution, Viking travels and minstrel shows, song fragments that survived for nearly a millennium, wonderful artists from Scottish poet Robert Burns to Kathy Mattea. There is so much love and passion for the history, the music, the instruments, the people, the land. There’s a CD bound into the back cover so you can hear the music, with every track explained in fascinating detail. There are dozens of handsome full page photographs that provide a sense of the land, plus illustrations of the instruments. Every time I wanted to know more about an interesting concept, I’d turn the page and find a very comprehensive briefing on, for example, “The Ceili, or Ceilidh” (a social event with music that originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in Scotland and Ireland); the dulcimer; “Child ballads” (Scots and Irish ballads classified by Harvard Professor Francis James Child, and often referred to by their numbers). I had never heard of The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. but now I understand its importance. Before Ellis Island, Philadelphia was the American point of entry for most immigrants from Ulster. They’d travel this early highway west and then south, ferrying across the Susquehanna River to Winchester, Virginia (home of Patsy Cline) and the Shenandoah Valley and on to the Yadkin Valley terminus in North Carolina (think in terms of today’s Boone, NC); Daniel Boone extended the trail to what became the Wilderness Road out to Kentucky’s Cumberland Gap.

Their story is told by Ms. Fisher’s nephew, Luke Barr in a book that’s becoming quite popular. It’s called Provence, 1970, and it provided a winter weekend’s entertainment. There are menus, and they lead into wonderful stories of friends building meals together– serious cooks experimenting and showing off for their foodie friends. It’s loose and informal, and I kept fantasizing about what it might have been like to join them, if just for a night. Few nonfiction books draw me into the story in quite this way, and it was fun to be a part of it, if only as an observer nearly fifty years later.

Their story is told by Ms. Fisher’s nephew, Luke Barr in a book that’s becoming quite popular. It’s called Provence, 1970, and it provided a winter weekend’s entertainment. There are menus, and they lead into wonderful stories of friends building meals together– serious cooks experimenting and showing off for their foodie friends. It’s loose and informal, and I kept fantasizing about what it might have been like to join them, if just for a night. Few nonfiction books draw me into the story in quite this way, and it was fun to be a part of it, if only as an observer nearly fifty years later. P.S.: I think I need to read more by M.F.K. Fisher. One intriguing title is a 1942 book called “How to Cook a Wolf.” I found a

P.S.: I think I need to read more by M.F.K. Fisher. One intriguing title is a 1942 book called “How to Cook a Wolf.” I found a

It’s a salad with the obvious fresh greens and toasted scallops, smaller than the ones we find in the U.S., and a bit saltier, too. There are bits of a local bacon, too, which enhances the salty favor. The sauce is a red pepper puree, which adds the necessary sweetness to balance the salty flavor. Bit of polenta toast complete the dish.

It’s a salad with the obvious fresh greens and toasted scallops, smaller than the ones we find in the U.S., and a bit saltier, too. There are bits of a local bacon, too, which enhances the salty favor. The sauce is a red pepper puree, which adds the necessary sweetness to balance the salty flavor. Bit of polenta toast complete the dish.

Just keep walking. Morning tea at the Florian, an old and not especially crowded coffee house (the first two weeks of December, nobody is in town, so I had the place to myself). It’s a landmark on the Piazza San Marco, and has been since the 1720s, when the Turkish invaders introduced coffee to the city. Casanova, Proust and Dickens hung out there, and now, so have I. The place is gorgeous, inside and out. I enjoy my $15 tea—it’s served in a clear teapot with a blooming cluster of leaves that open up as the tea brews. I contemplate the pigeons on the far side of the square—and the San Marco Basilica which seems to need a good cleaning. The treasured mosaics do not sparkle in the sunny day. They are obscured, in part, by inevitable scaffolding. The place is surrounded by expensive Fifth Avenue fashion shops, and Italian brands (Loriblu, for example, with splendidly silly crystalline boots in the window). Time to move on to more interesting surroundings. I keep walking. Time for lunch. Closed on Sundays (today is Thursday), the place to go is

Just keep walking. Morning tea at the Florian, an old and not especially crowded coffee house (the first two weeks of December, nobody is in town, so I had the place to myself). It’s a landmark on the Piazza San Marco, and has been since the 1720s, when the Turkish invaders introduced coffee to the city. Casanova, Proust and Dickens hung out there, and now, so have I. The place is gorgeous, inside and out. I enjoy my $15 tea—it’s served in a clear teapot with a blooming cluster of leaves that open up as the tea brews. I contemplate the pigeons on the far side of the square—and the San Marco Basilica which seems to need a good cleaning. The treasured mosaics do not sparkle in the sunny day. They are obscured, in part, by inevitable scaffolding. The place is surrounded by expensive Fifth Avenue fashion shops, and Italian brands (Loriblu, for example, with splendidly silly crystalline boots in the window). Time to move on to more interesting surroundings. I keep walking. Time for lunch. Closed on Sundays (today is Thursday), the place to go is  We chat for a bit, then I move on to a favorite campo in the Santa Croce area of town. It’s square dominated by a very old church called San Giacomo dell’Orio, and it dates back to 1225 (“Tradition says that the church

We chat for a bit, then I move on to a favorite campo in the Santa Croce area of town. It’s square dominated by a very old church called San Giacomo dell’Orio, and it dates back to 1225 (“Tradition says that the church

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor.

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor. That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.