There was a secret shared, and in time, the secret was widely shared. It was beautiful. Tasty and life-affirming, too. And many of us benefit from it every day of our lives.

Before 1970–give or take a few years either way–we ate frozen and canned foods, modern conveniences for the busy family. Fresh food wasn’t on the radar (and certainly not on the Radarange). Restaurants weren’t modern, not yet focused on locavores, or for that matter, shared cuisines beyond, say, a local pizza or Chinese restaurant.

What changed? Lots of cultural norms–greater awareness, shifted sensibilities, a focus on nutrition and fresh foods. This didn’t happen magically. It may have begun, in earnest, in 1970, when several iconoclasts gathered in nearby homes in the south of France. They changed the way we think about food, and if food is life, they changed the way we think about life, too.

They were Julia and Paul Child, whose rough contours were sketched in the film Julie & Julia. And, to a lesser degree, Simone Beck, who co-wrote “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” with Julia, and whose insistence upon classic French tradition emboldened Julia to think more clearly about the real world of American moms (few American dads cooked–except outdoors). There was the travel / food / free spirited writer M.F.K. Fisher and the American food expert James Beard, struggling through an extensive survey of our unique and sometimes inexplicable cuisine. And several others who cooked together, argued, and savory the good life that was making its way to Sonoma and Napa.

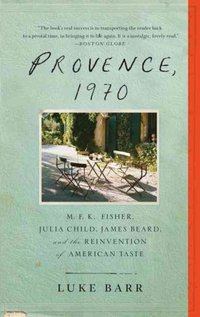

Their story is told by Ms. Fisher’s nephew, Luke Barr in a book that’s becoming quite popular. It’s called Provence, 1970, and it provided a winter weekend’s entertainment. There are menus, and they lead into wonderful stories of friends building meals together– serious cooks experimenting and showing off for their foodie friends. It’s loose and informal, and I kept fantasizing about what it might have been like to join them, if just for a night. Few nonfiction books draw me into the story in quite this way, and it was fun to be a part of it, if only as an observer nearly fifty years later.

Their story is told by Ms. Fisher’s nephew, Luke Barr in a book that’s becoming quite popular. It’s called Provence, 1970, and it provided a winter weekend’s entertainment. There are menus, and they lead into wonderful stories of friends building meals together– serious cooks experimenting and showing off for their foodie friends. It’s loose and informal, and I kept fantasizing about what it might have been like to join them, if just for a night. Few nonfiction books draw me into the story in quite this way, and it was fun to be a part of it, if only as an observer nearly fifty years later.

It’s now available in paperback, but there’s something about the hardbound edition that’s even more appealing.

Enjoy!

BTW: The complete title is “Provence, 1970: M. F. K. Fisher, Julia Child, James Beard, and the Reinvention of American Taste.” Here’s an excerpt, courtesy of NPR.

P.S.: I think I need to read more by M.F.K. Fisher. One intriguing title is a 1942 book called “How to Cook a Wolf.” I found a review of the book when it was new in the digital catacombs of The New York Times. They wrote:

P.S.: I think I need to read more by M.F.K. Fisher. One intriguing title is a 1942 book called “How to Cook a Wolf.” I found a review of the book when it was new in the digital catacombs of The New York Times. They wrote:

Mrs. Fisher writes about food with such relish and enthusiasm that the mere reading of her books creates a clamorous appetite. She also writes with a robust sense of humor and a nice capacity for a neatly turned phrase.”

It’s a salad with the obvious fresh greens and toasted scallops, smaller than the ones we find in the U.S., and a bit saltier, too. There are bits of a local bacon, too, which enhances the salty favor. The sauce is a red pepper puree, which adds the necessary sweetness to balance the salty flavor. Bit of polenta toast complete the dish.

It’s a salad with the obvious fresh greens and toasted scallops, smaller than the ones we find in the U.S., and a bit saltier, too. There are bits of a local bacon, too, which enhances the salty favor. The sauce is a red pepper puree, which adds the necessary sweetness to balance the salty flavor. Bit of polenta toast complete the dish.

Just keep walking. Morning tea at the Florian, an old and not especially crowded coffee house (the first two weeks of December, nobody is in town, so I had the place to myself). It’s a landmark on the Piazza San Marco, and has been since the 1720s, when the Turkish invaders introduced coffee to the city. Casanova, Proust and Dickens hung out there, and now, so have I. The place is gorgeous, inside and out. I enjoy my $15 tea—it’s served in a clear teapot with a blooming cluster of leaves that open up as the tea brews. I contemplate the pigeons on the far side of the square—and the San Marco Basilica which seems to need a good cleaning. The treasured mosaics do not sparkle in the sunny day. They are obscured, in part, by inevitable scaffolding. The place is surrounded by expensive Fifth Avenue fashion shops, and Italian brands (Loriblu, for example, with splendidly silly crystalline boots in the window). Time to move on to more interesting surroundings. I keep walking. Time for lunch. Closed on Sundays (today is Thursday), the place to go is

Just keep walking. Morning tea at the Florian, an old and not especially crowded coffee house (the first two weeks of December, nobody is in town, so I had the place to myself). It’s a landmark on the Piazza San Marco, and has been since the 1720s, when the Turkish invaders introduced coffee to the city. Casanova, Proust and Dickens hung out there, and now, so have I. The place is gorgeous, inside and out. I enjoy my $15 tea—it’s served in a clear teapot with a blooming cluster of leaves that open up as the tea brews. I contemplate the pigeons on the far side of the square—and the San Marco Basilica which seems to need a good cleaning. The treasured mosaics do not sparkle in the sunny day. They are obscured, in part, by inevitable scaffolding. The place is surrounded by expensive Fifth Avenue fashion shops, and Italian brands (Loriblu, for example, with splendidly silly crystalline boots in the window). Time to move on to more interesting surroundings. I keep walking. Time for lunch. Closed on Sundays (today is Thursday), the place to go is  We chat for a bit, then I move on to a favorite campo in the Santa Croce area of town. It’s square dominated by a very old church called San Giacomo dell’Orio, and it dates back to 1225 (“Tradition says that the church

We chat for a bit, then I move on to a favorite campo in the Santa Croce area of town. It’s square dominated by a very old church called San Giacomo dell’Orio, and it dates back to 1225 (“Tradition says that the church

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor.

Why did I care about this particular theater? The history, mostly. And the way it looks on the inside. Just being there, even if there isn’t the same there that was there before. This is the opera house where Verdi’s “La Traviata” made its debut. Same for “Simon Boccanegra,” where Maria Callas became a star. It is, or was, a remarkable place in the history of music. Why the dancing verbs? Because the place has a history that’s as crazy as any opera plot. Originally built as the San Benedetto Theatre in the 1730s, it burned down in 1774, and was rebuilt as Teatro La Fenice (“Fenice” translates as “phoenix”) to begin anew in 1792. Immediately, there was squabbles, the theater survived and by early 1800s, it was a world-class venue, mounting operas by Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, the big names in Italy at that time. In 1836, it burned down again, and was quickly rebuilt a year or so later. That’s when Verdi started writing operas for La Fenice, including “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata,” which debuted there. So began a century and a half of magic—until 1996, when two electricians burned it to the ground. Remarkably, engineers had measured the theater’s acoustics only two months before, so the theater was rebuilt sounding much the same as its predecessor. That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

That’s the theater that I visited, the 1,000 seat theater that hosted the premiere of “La grande guerra (vista con gli occhi di un bambino)” – a

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.

The contrast was fun to contemplate. On the one hand, a classic old opera house rebuilt from its own ashes less than twenty years ago presenting material from World War I in a 21st century setting. On the other, an old mansion dating back two centuries— Ca’Barbagio presenting an opera that debuted at La Fenice in 1853 for 21st century tourists visiting an old city of just 50,000 permanent residents whose long decline probably began more than 500 years ago. Today, the city exists mostly for its history and tourism—more than 20 million people visit Venice every year. I was lucky enough to spend my time at La Fenice sitting next to a local woman, Mirella, whose love for La Fenice has less to do with classic old operas and more to do with the many contemporary works, like those by Ambrosini, for this is, after all, her neighborhood music house.