A new book about pastels from artist Jean Hirons. If you buy it by clicking on the link (instead of buying from a more traditional source, the author earns more money for her self-published effort when you click on the book cover and make the purchase through Author House).

Ten or fifteen years ago, I decided to try my hand at pastels. That is, I bought a box of pastels, some paper, and started making bad art. At the time, there were two useful books available: Bill Creevy’s “The Pastel Book,” and Larry Blovits’s “Pastel for the Serious Beginner.” Both of these books were well-organized, and helpful, but neither provided the complete education that I wanted to pursue.

Over time, I bought more (and more) (and more) pastels, experimented with various types of paper, played with and decided that I pretty much hated fixative, bought a field easel, and started spending weekend afternoons making pastel paintings. To be honest, I didn’t much care whether each painting was worth showing to anybody; most of the paintings were wrapped in glassine (which does not smudge the painting) and placed, ever so carefully, into a box. Mostly, my concern has been learning how to pursue a creative process.

Along the way, I have bought just about every book about pastels that I could find. I’ve scoured the lists of the top publishers (then, North Light Books and Watson-Guptill, the latter now part of North Light). I’ve been inspired by the beautiful work and eye-opening creative thinking so elegantly presented by Elizabeth Mowry her two best books, “The Pastelist’s Year,” which looks at painting through the seasons) and “The Poetic Landscape,” which examines perception and the psychology of art through pastel painting. Both of Maggie Price’s books have proven very useful: “Painting with Pastels” and the more specialized “Painting Sunlight and Shadows with Pastels.” The out-of-print book that taught me ever so much was Doug Dawson’s “Capturing Light and Color with Pastel.” The more sophisticated, and modestly entitled, “Pastel Pointers” by Richard McKinley, is only part of a larger instructional program that can be pursued online or in the always-excellent Pastel Journal magazine.

Still, I wish I was just starting out today, if only to do so under the guidance of Jean Hirons and her new (self-published) book, “Finding Your Style in Pastel.”

From the very first image on the very first page, I sensed, I can probably do this. Immediately, my confidence level increased. A brief but substantive review of types (soft, hard) and brands (Sennelier, NuPastel) is followed by a rundown on the many surfaces (papers, mostly) now available (with running commentary on the advantages of each ground), and comments on strokes, blending, layering, and other techniques. I like the way Ms. Hirons keeps the story moving; she makes her points clearly and with the right illustrations, then moves on. (She is my kind of teacher!) There’s a lot of “show me what I need to know,” as with a quartet of small images to explain toning and underpainting (two methods of pre-painting a surface).

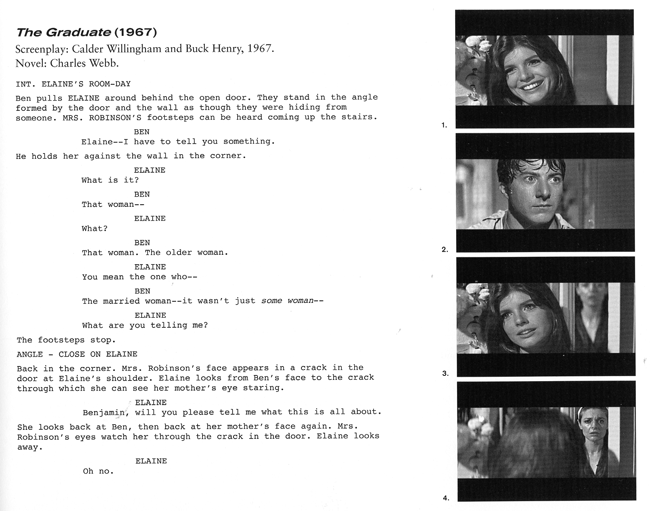

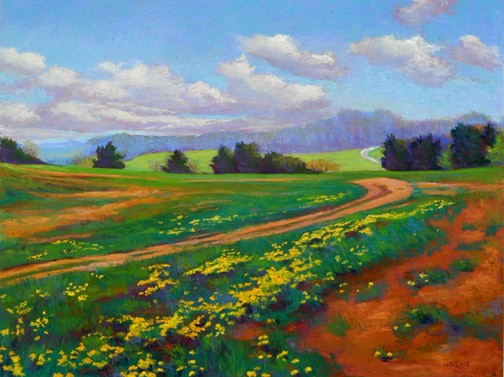

By page 63, she’s defining personal styles. This is, of course, what every artist wants to know. Basic techniques are fine, but how do I make my paintings my own? So begins one of the better explorations of composition, value, edges and color theory that I’ve seen in book form. As with the earlier chapters, the author does not linger; the pace remains solid, brisk and professional. Once again, two images from the artist’s online gallery help to make the point about the difference between the works of an artist who pursues a distinctive, personal style:

Same artist, different seasons, different color palettes, varying levels of edge sharpness, atmospheric color, amount of foreground detail, use of line and shape, mood, overall colorcast, color temperature, and so much more.

Hirons rarely insists upon one particular technique or approach. Instead, she runs through available options, the techniques required to achieve the desired effects, and well-chosen images to illustrate each point.

Along the way, she also addresses the questions that lurk in the back of every pastelist’s mind. To what extent do I paint the colors that I observe? How do shadows work: how dark, how much local color, how much should I shift the color temperature? How far should I go with my interpreted color? To what extent, and under which conditions, should I pursue abstraction?

Yes, there are some step-by-step demonstrations, but only a few (I’ve never been a big fan of books filled with step-by-step demos because I tend to lose interest unless I am actually painting at the same time as I am reading). Hirons uses them only in her final problem solving chapter (where they can do the most good).

In one of several appendices, the author recommends books about art, color, composition, landscapes, and, inevitably, pastels. Somehow, her list of recommended titles (which I just found as I was writing this last sentence) matches my list (at the top of this article) just about one-for-one. She adds “Pure Color,” a compendium of excellent pastel work by contemporary artists. To her list of materials sources, I would certainly add the venerable New York Central Art Supply near Greenwich Village.

Over time, self-published books can become hard-to-find (the author depletes the current stock and may or may not decide to continue to be a publisher–an especially challenging decision for an artist who is not, by trade, a publishing mogul). That’s why I always recommend that a self-published book be purchased immediately. In this case, the bound book–a 200-page, full color, very handsome paperback–costs just over $50, but the same book can be purchased for just $3.99 as an eBook. Despite my interest in all things digital, I would opt for the paperbound edition because I like surrounding myself with very good books. And this one fits, very nicely indeed, into that category.

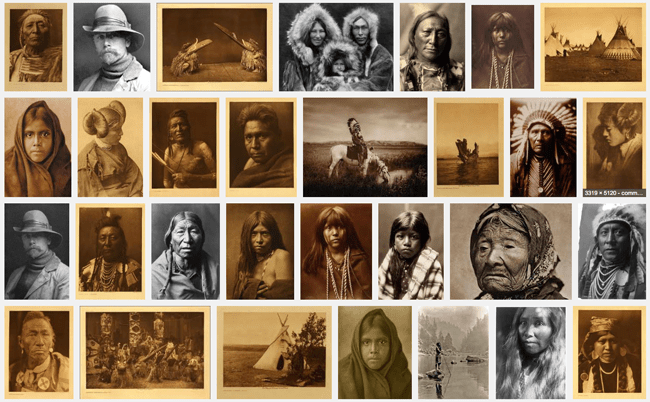

The woman in the photograph was a poor soul, without friends, the subject of ridicule among Seattle schoolchildren. She lived in a hovel. When the growing city of Seattle cleared its native population, she remained where she was, and the city grew up around her. Kick-is-om-lo was her name, but that was difficult to pronounce, so the local folk called her Princess Angeline. In 1896, Kick-is-om-lo was paid one dollar to pose for this picture–the equivalent of what she was able to earn in a whole week–by a struggling young photographer named Edward Curtis. To say this would be the first of many such images would be a substantial understatement.

The woman in the photograph was a poor soul, without friends, the subject of ridicule among Seattle schoolchildren. She lived in a hovel. When the growing city of Seattle cleared its native population, she remained where she was, and the city grew up around her. Kick-is-om-lo was her name, but that was difficult to pronounce, so the local folk called her Princess Angeline. In 1896, Kick-is-om-lo was paid one dollar to pose for this picture–the equivalent of what she was able to earn in a whole week–by a struggling young photographer named Edward Curtis. To say this would be the first of many such images would be a substantial understatement.

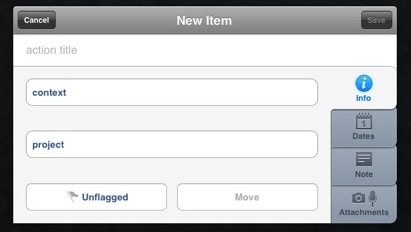

Although it is possible to make a quick task entry, the more complete entry panel is more useful. After naming the task, I select a context from my own list that includes: Awaiting Response, Call, Create, First Contact, Followup, Just Do It, On Hold, Purchase, Research, Schedule, Visit Web Site, and Write. Then, I select a project, again from my own list that includes: Art, Books, Digital Insider, Home, Music, Software, Travel, Web Site, and various, specific work-related projects. I can stop there, deciding to add a flag to any high-priority tasks, but I prefer to add a due date to every task (start dates are also an option, but I don’t work that way). There’s a nice big note field, and I use hat to capture URLs, reminders of the most recent attempted contact (left phone message on 3.13.2013; sent reminder email on 10.12.2012). I can add a photograph, .jog, .gif, .png, or record an audio message.

Although it is possible to make a quick task entry, the more complete entry panel is more useful. After naming the task, I select a context from my own list that includes: Awaiting Response, Call, Create, First Contact, Followup, Just Do It, On Hold, Purchase, Research, Schedule, Visit Web Site, and Write. Then, I select a project, again from my own list that includes: Art, Books, Digital Insider, Home, Music, Software, Travel, Web Site, and various, specific work-related projects. I can stop there, deciding to add a flag to any high-priority tasks, but I prefer to add a due date to every task (start dates are also an option, but I don’t work that way). There’s a nice big note field, and I use hat to capture URLs, reminders of the most recent attempted contact (left phone message on 3.13.2013; sent reminder email on 10.12.2012). I can add a photograph, .jog, .gif, .png, or record an audio message.

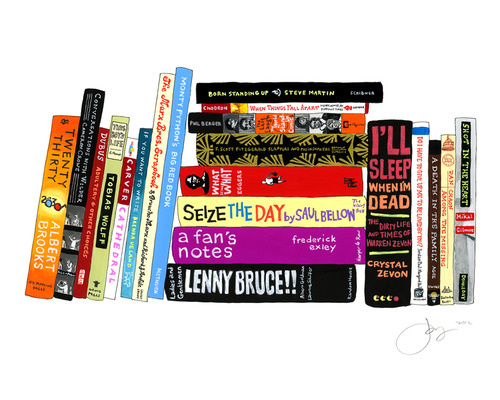

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh.

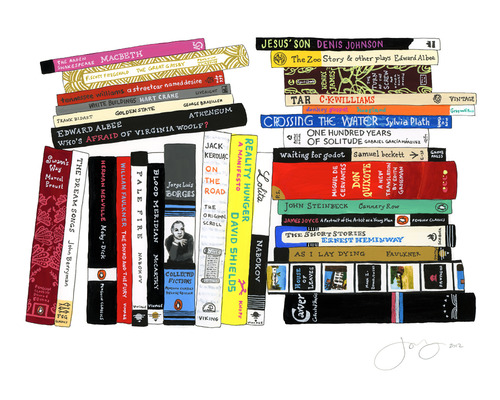

Judd Apatow, famous for his comedy movies, surprised me with James Agee’s A Death in the Family, and reminded me of a popular book about comedians that I wanted to read, but never did: The Last Laugh. James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

James Franco wins for the most cluttered bookshelf, also the one with the most books. From his stacks, I think I will pick up another set of Raymond Carver stories, and the original scroll version of Kerouac’s On The Road. I suppose I should read Melville’s Moby Dick, which I have avoided so far for no good reason. Ditto for writer Philip Gourevitch’s suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.