Ford Model T, circa 1910. By 1916, you could buy one for $850 or rent one for 10 cents a mile.

Robotic cars that drive themselves–that’s the comic book version of the future currently in advanced stages of development at Google, Mercedes-Benz, and, I would guess, just about every significant vehicle and technology maker on earth. Before the end of the 2020s, these cars will be as common as a Toyota Prius. In theory, cars that drive themselves will reinvigorate the automotive industry.

But that’s not the big story.

For a moment, think about your telephone(s). In your pocket or bag, you carry an expensive digital multi-purpose device that multitasks as a telephone, messaging center, emailer, web browser, camera, clock… so on. At home, you may still pay for a relatively stupid device that is little more than an old school telephone. Which one will go away? Easy answer.

Now, transpose that thinking to the car of the future. It’s foolish to impose old expectations on a new paradigm. A digital car will probably reinvent the whole idea of cars as well as our relationship with personal vehicles. We saw the start of this idea with rental cars. ZipCars showed up in the US around 2000, an idea borrowed from Europe. City dwellers and college students are Zip’s best customers because the opportunity to pay a membership fee for occasional use of a car is more sensible than owning, maintaining, parking, and otherwise caring for a physical product. In essence, ZipCar transfers the customer relationship from product purchase to service/subscription.

From last weekend’s Wall Street Journal:

Brace yourself. In a few years, your car will be able to drop you off at the door of a shopping center or airport terminal, go park itself, and return when summoned with a smartphone app.”

Presumably, the new cars won’t crash–saving enough lives to repopulate Newport, Rhode Island or Key West, Florida every year, and then some.

From the same WSJ article:

private vehicles spend 90% of their time parked and unoccupied

Let’s pull together several ideas. Texting while driving is just plain dumb. And yet, for most people, driving a car is less interesting than playing with an iPhone. If there was some way to move from place to place and allow texting (or emailing, playing a game, or learning), that might be preferable to our 2013 status quo. Me, I’m happier reading a book than doing daily battle with aggressive trucks exceeding the interstate’s speed limit. Let my digicar’s radar system, wide-baseline stereoscopic camera, massive processing power (think: computer chess applied to the calculus of high-speed traffic or crazy curvy country roads). Let vehicles talk to one another (“hey, I’m in the wrong lane–would you please slow down so that I can make that right hand turn coming 2.348 feet at longitude X and latitude Y?” “sure, anytime, have a nice day”)

How does EZ-Pass and privacy fit into all of this? For those who still honestly believe that their travels are not easily recorded, stored and compared with every shopping receipt, it’s both another loss of freedom and another realization that privacy is something that one cannot easily or simply protect in a digital age. Certainly, this information could become the property of bad people (or governments or large corporations, who may or may not define ‘reasonable’ as individuals do).

A digital car would certainly know where it is going, where it has been, and where it needs to go. And it would know, and record, passenger identities. When traveling, we’ve been balancing time, money and privacy for a long time. Here’s the current situation–consider how similar a digicar service and the “rental” of your airline seat can be:

If I want to travel from Times Square to Hollywood, I can drive for about 40 hours (more, if there’s traffic, but my digicar might know how to circumvent it). If I drive 8 hours/day, that’s 5 days of driving, 4 hotel nights (about $500), and 2,800 miles (100 gallons of gas, or about $400 worth), plus wear-and-tear of about $200 (if all goes well)–5 days of my life plus over a $1,000 of my money. I could take the train for 20 hours and spend about $450, but if I want to sleep on the train, it’s 43 hours and $1,200, plus the time and money required to get to and from the train stations. If I fly, my time expense is about 8 hours door-to-door and my dollar expense is $500 including ground transportation. Train and air travel requires me to surrender personal information about my identity and my precise travel plans; car travel does not (except when I use a credit card to fill the tank, which I will do about 8 times, pay a toll with EZ-Pass, or sleep in a hotel, or eat, making it easy to track my progress).

A long paragraph for a short idea: we routinely exchange privacy for time and money. Are we ready to surrender those expensive machines that sit idle all but 10% of their lives. Is the car of the future more likely to be a product (buy one at your local Ford dealer) or a service (lease one with an app, or sign up for a rental subscription service).

The answer is pretty clear to me. After the vehicle drops me off at the supermarket, I don’t much care what it does or where it goes, and, in most situations, I don’t care whether it’s Holly, Dolly, Lolly, Molly or Folly The Digital Car that picks me up when I’m ready to go home. I just want to know that it will be there, on time, clean, reliable, capable, and right-sized for my needs (smaller if I have no bags). If I need the car for an extended period, I’m sure I could pay a higher subscription rate, perhaps by the month or year, perhaps by the trip. Will I be able to reserve? Will the vehicle show up? What if we get lost? What if there aren’t enough cars?

How many cars is enough cars? Right now, we’ve got about a billion cars for about seven billion people on planet earth–but that’s only because China’s ratio is about 7 people to one vehicle (in the US, it’s about 1.3 people per car).

More cars, more roads, more paved-over nature, more crowded national parks, more traffic jams, more stress on an interstate infrastructure that’s already stressed. Fewer cars? How about more efficient use of the whole idea of cars? Think about my imperfect math: if every car’s use was doubled in its efficiency, and was used 50% of the time, maybe we could reduce the number of cars on the planet by a third or more. If the cars were smart enough to avoid accidents, there would be no more time or energy spent on drinking and driving, or texting while driving, and no more arguments between teenagers who are probably too young to drive and parents who are terrified every time their child backs up out of the driveway.

For details about specific companies and their progress, click on the Wall Street Journal’s car below.

It’s a big, old book, the kind of illustrated, illuminated, hand-lettered book that I would never expected to see in my own home. But here it is, nearly 2 inches thick, reproduced by the always-intrepid Taschen publishing company. As you can see, it’s quite a beautiful old book, with colorful illustrations of kings and townscapes on every page. Looking carefully, I can make out a page about Florencia, also known as Florenz, today’s Florence, Italy, and on another page, the now-German town of Wurtzburg. There’s Rom, or Roma, with its bridges and towers, and the formidable city gates. Here’s a stylist family tree, but the old lettering is difficult for me to understand. A book like this might occupy a few minutes in a museum, and then, I’d move on. But to have it in my hands, well, that’s another thing. Its age demands respect, and time to study, not to peruse but to study, every page, slowly and with a sense of insight and discovery.

It’s a big, old book, the kind of illustrated, illuminated, hand-lettered book that I would never expected to see in my own home. But here it is, nearly 2 inches thick, reproduced by the always-intrepid Taschen publishing company. As you can see, it’s quite a beautiful old book, with colorful illustrations of kings and townscapes on every page. Looking carefully, I can make out a page about Florencia, also known as Florenz, today’s Florence, Italy, and on another page, the now-German town of Wurtzburg. There’s Rom, or Roma, with its bridges and towers, and the formidable city gates. Here’s a stylist family tree, but the old lettering is difficult for me to understand. A book like this might occupy a few minutes in a museum, and then, I’d move on. But to have it in my hands, well, that’s another thing. Its age demands respect, and time to study, not to peruse but to study, every page, slowly and with a sense of insight and discovery. Fortunately, the cardboard slipcase includes not only the main volume, but a large-format color paperback book entitled The Book of Chronicles. In essence, it’s a guidebook, written in English, nicely illustrated, and it helps to make sense of the larger volume. It begins,

Fortunately, the cardboard slipcase includes not only the main volume, but a large-format color paperback book entitled The Book of Chronicles. In essence, it’s a guidebook, written in English, nicely illustrated, and it helps to make sense of the larger volume. It begins,

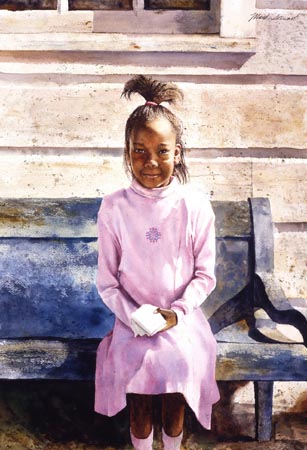

Every once in a while, I’ll find an artist on the web whose work I truly admire. I recently stumbled upon a Texas watercolorist named Mark Stewart, and I thought you might enjoy seeing some of his work. Of course, there’s no reason why you should read any of what I have to say… just go directly to his

Every once in a while, I’ll find an artist on the web whose work I truly admire. I recently stumbled upon a Texas watercolorist named Mark Stewart, and I thought you might enjoy seeing some of his work. Of course, there’s no reason why you should read any of what I have to say… just go directly to his

Birthday: August 4, 1961

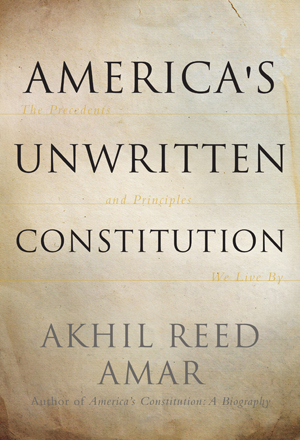

Birthday: August 4, 1961 I started reading Amar’s book,

I started reading Amar’s book,

On September 20, 2013, the U.S. Postal Service was ordered to pay well over a half-million dollars to Frank Gaylord. He is a sculptor, the artist responsible for the

On September 20, 2013, the U.S. Postal Service was ordered to pay well over a half-million dollars to Frank Gaylord. He is a sculptor, the artist responsible for the

(For cameras with a hot shoe–the place where you would insert a flash, a similar model is available. The difference: the magnifier is suspended from the top, not connected to the bottom of the camera.)

(For cameras with a hot shoe–the place where you would insert a flash, a similar model is available. The difference: the magnifier is suspended from the top, not connected to the bottom of the camera.)