“The store was often empty for a couple of hours at a time, and then, when somebody did come in, it would be to ask about a book remembered from the Sunday-school library, or a grandmother’s bookcase, or left behind twenty years ago in a foreign hotel. The title was usually forgotten, but the person would tell me the story….Then, they would leave without a glance at the riches around them….A few people did explain in gratitude, said what a glorious addition to the town. They would browse for a half an hour, an hour, before spending seventy-five cents.”

“The store was often empty for a couple of hours at a time, and then, when somebody did come in, it would be to ask about a book remembered from the Sunday-school library, or a grandmother’s bookcase, or left behind twenty years ago in a foreign hotel. The title was usually forgotten, but the person would tell me the story….Then, they would leave without a glance at the riches around them….A few people did explain in gratitude, said what a glorious addition to the town. They would browse for a half an hour, an hour, before spending seventy-five cents.”

The words were written by Alice Munro and published in a novella called The Albanian Virgin” by the New Yorker magazine in 1994. They came to mind because Penelope Fitzgerald’s brief 1978 novel about an unwanted bookshop, The Bookshop, was recently released in as a film starring Emily Mortimer (familiar to US audiences from her role in Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom series).

Roaming around Manhattan yesterday, and wandering into a wonderful neighborhood shop called The Corner Bookstore on the Upper East Side. It was a pleasant place to spend an hour, and spend money on two books (one about architecture for me, one about birds as a gift). Perhaps pleasant is the wrong word. It was an irresistible place to spend an hour because the books were fetchingly arranged to capture my imagination.

The role of the contemporary bookstore isn’t very different from its role a century ago. It’s a fine place to explore ideas and stories, to examine the cover art and the typography, to physically handle the books and enjoy their new-ness. Certainly, Amazon has changed the plumbing, but the relationship between book and consumer, and book and reader, would be familiar to Dickens, or for that matter, Mao (who once was a bookseller).

I know that because of Jorge Carrión, who published a book last year called Bookshops: A Reader’s History, a product best enjoyed when and if purchased from a local bookseller. It’s fun to travel the world with Carrión, and to travel through history, too. There is no true beginning to the journey, but the author contemplates the importance of the great library at Alexandria as a kind of starting place for available collections of printed works. He’s unsure whether Librarie Kauffmann in Athens is still in business, but he tells the story anyway: it grew from a book stall selling second-hand goods, then became the center of thought, literacy and enlightenment for French speaking families, scholars, and intellectuals in Athens in the 20th century. He describes it as “one of those bookshops to get a stamp on your imaginary bookshop passport.”

William Thackery probably shopped at 1 Trinity Street in Cambridge, a site that has sold books for about 600 years, but necessarily to the public. In Krakow, there’s Matras, which used to be called Gebether and Wolf, and it dates back to the 1610, though not with an entirely continuous history. P&G Wells is probably the oldest bookstore in England–this Winchester shop can show you receipts dating back to 1729. Click on the picture to visit their modern website.

History is well-captured in this September 26, 1786 bit from Goethe, written in his journal published as Italian Journey:

“I had entered a bookshop which, in Italy, is a peculiar place. The books are all in stitched covers, and at any time of the day, you can find good company int he shop. Everyone who is in any way connected with literature–secular clergy, nobility, artists–drop in. You ask for a book, browse in it, or take part in a conversation as the occasional arises. There were about a half dozen people there when I entered, and when I asked for the work of Palladio, they all focused their attention on me. While the proprietor was looking for the book, they spoke highly of it and gave me all kinds of information about the original edition and the reprint. They were all acquainted with the work, and with the merits of the author.”

What fun–it’s easy to imagine finding myself in the very same situation.

There is now an assortment of books about bookstores on my home shelves. One illustrates favorite bookstore facades in pen-and-ink and watercolor. Another describes favorite booksellers with stories about the stores and the people who inhabit them. I haven’t started to list or photograph bookstores that happen along the way as I travel, but Aqua Alta in Venice would certainly deserve a mention because you can climb a pile of books for a look at the adjacent canal. Scrivener’s in Derbyshire is probably worth a trip to England just to browse a few tens of thousands of volumes, but that should probably be scheduled to coincide with a day or a week in Hay-en-Wye, in Wales, which is an entire town devoted to bookshops and things literary. It’s now one of several book towns around the world. And yes, there is a book about these book towns–I very nearly bought it yesterday at The Corner Bookstore–and for course it’s called Book Towns. Someday, because I am now reading far too many books and articles about books and the places where you can bu them–I will visit Argentina. That’s because Jorge Carrión, and others, have told me about a spectacular old movie theater that is now a bookstore called Ateneo. Between now and my visit, I will need to learn to read Spanish, but that won’t stop me from browsing.

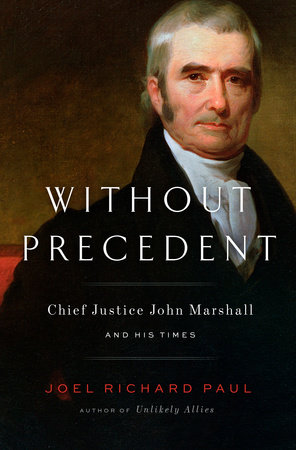

He wasn’t a rich man, and he wasn’t a well-educated man. “Marshall grew up in a two-room log cabin shared with fourteen siblings on the hardscrabble frontier of Virginia. His only formal education consisted of one year of grammar school and six weeks of law school.” And yet–this is the part that would make a terrific Broadway musical, or perhaps even an opera–Marshall becomes a military officer, influential attorney of local and then national renown, a diplomat to France, a congressman, U.S. Secretary of State, the biographer of George Washington, and eventually, the first really effective chief justice of the new United States of America (John Jay was the first, but the high court was just beginning to take shape; he was followed by one short-termer whose nomination went unapproved, and another, who was also operating in the early days of our judicial system).

He wasn’t a rich man, and he wasn’t a well-educated man. “Marshall grew up in a two-room log cabin shared with fourteen siblings on the hardscrabble frontier of Virginia. His only formal education consisted of one year of grammar school and six weeks of law school.” And yet–this is the part that would make a terrific Broadway musical, or perhaps even an opera–Marshall becomes a military officer, influential attorney of local and then national renown, a diplomat to France, a congressman, U.S. Secretary of State, the biographer of George Washington, and eventually, the first really effective chief justice of the new United States of America (John Jay was the first, but the high court was just beginning to take shape; he was followed by one short-termer whose nomination went unapproved, and another, who was also operating in the early days of our judicial system). The fun begins in York about 10,000 years ago. The Romans showed up about 2,000 years ago–certainly by 71 AD–and you can walk the

The fun begins in York about 10,000 years ago. The Romans showed up about 2,000 years ago–certainly by 71 AD–and you can walk the  After the Vikings, York weathered a less distinguished period. One of the worst episodes: the burning of Jews supposedly under government protection in the 1100s–an old castle is still on the site. By 1300, York was both an important government and trading center for England, and remained so until the 1500s. You can walk the streets and see medieval buildings–not unlike walking the world of Harry Potter (celebrated by several souvenir shops).

After the Vikings, York weathered a less distinguished period. One of the worst episodes: the burning of Jews supposedly under government protection in the 1100s–an old castle is still on the site. By 1300, York was both an important government and trading center for England, and remained so until the 1500s. You can walk the streets and see medieval buildings–not unlike walking the world of Harry Potter (celebrated by several souvenir shops).

What have I missed? The quiet pub where the World Cup semi-final victory for England was celebrated in a most dignified manner. The streets outside where everyone’s cheeks (probably both kinds) were painted with tiny English soccer flags, where people sang, loudly with with tremendous dancing exuberance, about how the Cup was “coming home.” Nearly every pub in town was pounding with energy and music–including, inexplicably, “Take Me Home Country Roads” and other boisterous (?) John Denver tunes to which every Brit seemed to know every word; the medley ended with the British (?) classic, “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” All great fun!

What have I missed? The quiet pub where the World Cup semi-final victory for England was celebrated in a most dignified manner. The streets outside where everyone’s cheeks (probably both kinds) were painted with tiny English soccer flags, where people sang, loudly with with tremendous dancing exuberance, about how the Cup was “coming home.” Nearly every pub in town was pounding with energy and music–including, inexplicably, “Take Me Home Country Roads” and other boisterous (?) John Denver tunes to which every Brit seemed to know every word; the medley ended with the British (?) classic, “Cotton-Eyed Joe.” All great fun!

The tiger is George’s Clemenceau, great friend of hedgehog Claude Monet, who turns out to be the last of the impressionists. The story picks up long after Monet had moved to his lovely garden home in Giverny, about halfway upriver from Paris on the way to Rouen. And may recall Rouen because that’s home to the ancient cathedral that Monet painted more than thirty times under all sorts of light. Monet was that kind of artist—obsessive, meticulous, perfectly happy to spend endless hours interpreting the London fog or wheat stacks (similar to hay stracks) not far from his home in the country. When author Ross King picks up Monet’s story, the artist is less enthusiastic about travel, but eager to serve and take healthy part in a lavish lunch before touring the beautiful Giverny garden, visiting the pond and lily pads, or showing off his latest work, most often very large paintings. By now, Monet is far more active than many men his age, still active enough to build a new studio adjacent to the house and fill it with new paintings. Cataracts and other health problems make seeing, and therefore painting with the specific colors he requires, a terrifying challenge. And there is a Great War on the horizon, so his life’s work may be destroyed by the German forces already notorious for precisely this sort of mayhem.

The tiger is George’s Clemenceau, great friend of hedgehog Claude Monet, who turns out to be the last of the impressionists. The story picks up long after Monet had moved to his lovely garden home in Giverny, about halfway upriver from Paris on the way to Rouen. And may recall Rouen because that’s home to the ancient cathedral that Monet painted more than thirty times under all sorts of light. Monet was that kind of artist—obsessive, meticulous, perfectly happy to spend endless hours interpreting the London fog or wheat stacks (similar to hay stracks) not far from his home in the country. When author Ross King picks up Monet’s story, the artist is less enthusiastic about travel, but eager to serve and take healthy part in a lavish lunch before touring the beautiful Giverny garden, visiting the pond and lily pads, or showing off his latest work, most often very large paintings. By now, Monet is far more active than many men his age, still active enough to build a new studio adjacent to the house and fill it with new paintings. Cataracts and other health problems make seeing, and therefore painting with the specific colors he requires, a terrifying challenge. And there is a Great War on the horizon, so his life’s work may be destroyed by the German forces already notorious for precisely this sort of mayhem. He is also an extraordinarily difficult, insecure, proud man who feels that he must do more for France, provided that doing more is possible on his own exacting terms.

He is also an extraordinarily difficult, insecure, proud man who feels that he must do more for France, provided that doing more is possible on his own exacting terms. Author

Author