I was quite taken with Ellen Eagle’s new book, Pastel Painting Atelier. It’s a classy book, hardcover and quite beautiful, as this atelier series tends to be. Unlike most books about art, unlike most books written for creative people, this one provides several hours of quiet time with the artist at work in her studio, in her mind, with her eyes, with her hands. She sees beauty in the tiniest of details: the curve of the silhouette of a woman’s face, the arrangement of the old pipes beneath the even older sink in the corner of a Manhattan studio, the private thoughts that take shape in a best friend’s eyes.

Here and there, the book is an instructional work for artists who wish to perfect their pastel technique, but that’s a small part of the whole. (In fact, the obligatory step-by-step demonstrations that end the book are its least essential part). The best parts are small comments that accompany the many sensitive images, often of women who might, in a glance, be dismissed as ordinary. Eagle describes her model, Mei-Chiao, as follows: “the inward gesture of the head to the chest was beautiful to me, and the backward pull of the shoulders is balanced by the triangular opening blouse neckline.” Minor details become a beautiful painting. Same girl, different painting, one that I found by exploring Ellen Eagle’s portrait website, an endeavor I recommend when you have the time to look carefully…

The artist’s use of line and color is quite masterful, and throughout the book, it’s easy to get lost in page after page of exquisite, often subtle, portraits. She has a knack for capturing women especially well, almost as if she is drawing and painting their minds as well as their fine features. One of my favorites is below, also taken from her website. She describes the painting below as follows: “In Roseangela’s flesh, I saw warm yellow-greens co-mingling with touches of cool violets and pinks. The planes that faced the light contained color pinks, blues, and greys. Warm tones ran throughout the flesh. Warm, dark burnt sienna defined the depths of her eye sockets. Where the orange dress caught the light, the colors took on a cool temperature. The weight of her clasped hands pulled the dress inward, causing a slight angle away from the light, and the cooler tones gave way to warmer ones.” It’s almost as if she’s writing a poem with colors.

This is a gentle book, an inspirational one with the promise of some instruction for the visual artist, but you need not be an artist to see what she sees, and to enjoy the way that Ms. Eagle perceives and so lovingly sees the world.

Here’s the cove. The image on the cover is another favorite. The artist was especially taken with the pose struck by the model. Be sure to visit Eagle’s website to see the uncropped version.

When the day winds down, my wife and I try to catch at least an hour’s worth of television viewing. Apart from two or three network series, we mostly forget that CBS, ABC, FOX, and NBC exist. We watch HBO, but never when the network schedules programs. Just about all viewing is on-demand, and nowadays, most of that viewing is done on Netflix.

When the day winds down, my wife and I try to catch at least an hour’s worth of television viewing. Apart from two or three network series, we mostly forget that CBS, ABC, FOX, and NBC exist. We watch HBO, but never when the network schedules programs. Just about all viewing is on-demand, and nowadays, most of that viewing is done on Netflix.

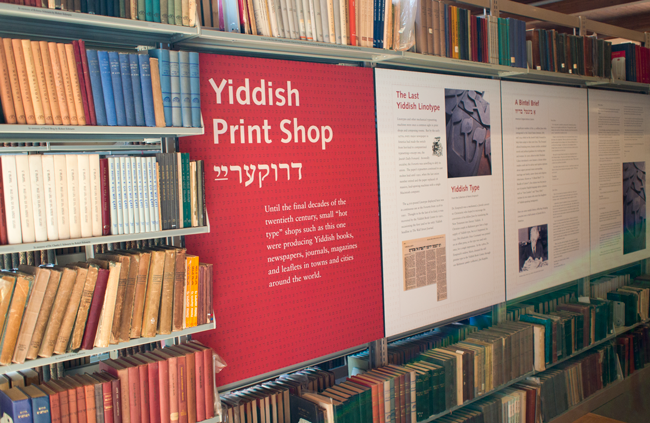

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.

At the very least, Lansky, his friends, his co-conspirators, the Center’s network of scholars and friends and donors, the network of zammlers (two hundred people who collect books worldwide for the Center) have taken the first step. We now have the books, and nobody is going to take them away from us. And they’ve taken the second step: the books are now available, through various re-disribution schemes, to people everywhere. The third step is the mind-bender. How to republish the works, maintaining the integrity and magic of their original words and ideas in a world where (a) the whole book publishing industry is trying to figure out its digital future and path to thrival (my made-up word that goes beyond survival into thriving); (b) few people read Yiddish; (c) Yiddish culture is becoming historical fact rather than a cultural reality; and (d) as interested as I may be, I don’t think I have every read a single Yiddish book, and apart from Sholom Alechem (whose work was the basis for Fiddler on the Roof), I don’t think I can name a single Yiddish author.