Ten or fifteen years ago, I read a really good biography of the photographer Ansel Adams. I’ve recommended it often, but somehow, I couldn’t find it on my shelves. A bit of curiosity and research led me to the author, Mary Street Alinder and her new book about Adams and his West Coast photography buddies and co-conspirators including Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Brett Weston (Edward’s son), Consuelo Kanaga, Dorothea Lange, and other notables. Sometimes formally, sometimes less so, they were collectively members of a group bound to change American photography. They called themselves Group f.64, which is both among the smallest lens apertures generally available (for extreme depth of field and its resulting sharp images) and the title of Ms. Alinder’s latest book.

When the photographers in Group f.64 started out, they found themselves in what, today, seems to be an unlikely situation. Photographers on the east coast followed a mostly European tradition anchored in painting. On the West Coast, the fad was pictorialism in which photographs were not considered viable unless they were altered to look like other forms of art. For example, the pictorial photographers often hand-colored their work, used soft focus lenses, and created faux brushstrokes during the photographic development process. Pictorialism found some rather odd expressions: one very popular West Coast photographer named William Mortensen was, according to Alinder, “the very vocal champion of the Pictorialists. He applied his expertise in set design and the latest in Hollywood makeup artistry: elaborately costumed historical portraits and tableaux. He staged each picture’s setting, building a fictional alternative universe, often of a teasing salaciousness or portraying scenes of horror, his models transformed into monsters with heavy makeup.” Mortensen was among America’s most famous photographers and easily photography’s most prolific teacher. In a series of well-described articles in Camera Craft magazine, he sparred with Ansel Adams who took the position of photography as pure art form that required none of the nonsense that Mortensen promoted.

When the photographers in Group f.64 started out, they found themselves in what, today, seems to be an unlikely situation. Photographers on the east coast followed a mostly European tradition anchored in painting. On the West Coast, the fad was pictorialism in which photographs were not considered viable unless they were altered to look like other forms of art. For example, the pictorial photographers often hand-colored their work, used soft focus lenses, and created faux brushstrokes during the photographic development process. Pictorialism found some rather odd expressions: one very popular West Coast photographer named William Mortensen was, according to Alinder, “the very vocal champion of the Pictorialists. He applied his expertise in set design and the latest in Hollywood makeup artistry: elaborately costumed historical portraits and tableaux. He staged each picture’s setting, building a fictional alternative universe, often of a teasing salaciousness or portraying scenes of horror, his models transformed into monsters with heavy makeup.” Mortensen was among America’s most famous photographers and easily photography’s most prolific teacher. In a series of well-described articles in Camera Craft magazine, he sparred with Ansel Adams who took the position of photography as pure art form that required none of the nonsense that Mortensen promoted.

From 1932—just a few years before those articles—the f.64 wrote a manifesto to explain its unique and somewhat radical approach to pure photography as an emerging art form. “Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technic [technique], composition or idea derivative of any other art-form.”

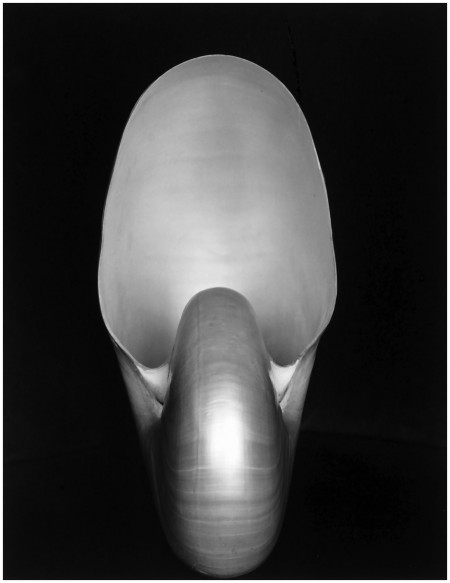

What did that mean? For Edward Weston, in 1927, pure photography involved making perfect images of a single pepper or a shell. What’s perfect? Have a look.

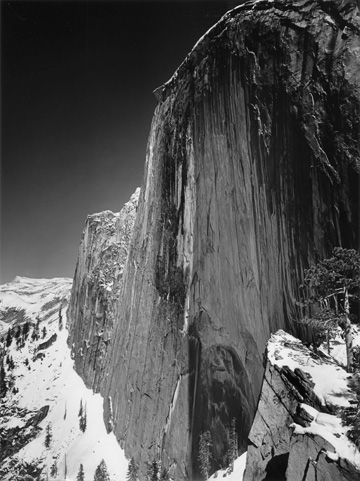

Also from 1927, Ansel Adams provides this example:

Time has not been kind to Mr. Mortensen, whose partial portfolio can be found on an Eastman House website:

Mostly, this is the story of perhaps a dozen fully engaged West Coast photographers whose clear vision redefined American fine art and serious amateur photography. In an attempt to gain serious recognition in New York City galleries—remember, the west coast was rather distant from the east in the 1930s—they solicited a largely unimpressed Alfred Steiglitz in what they believed to be photography’s future. You know Stieglitz’s extraordinary work:

In time, and with considerable frustration, the West Coast photographers found their way into the mainstream. The level of detail provided by Ms. Alinder may overwhelm casual readers, but it’s all worth reading to better understand the large aesthetic shift that occurred in what amounts to about twenty years, maybe thirty.

Where does the story lead? Clearly, Mr. Mortensen’s fascinations have faded from public interest, but the work of Ansel Adams continues to demonstrate the power of photography for the world to see (and for a great many amateur photographers to emulate). The shift from manufactured to realistic beauty is nicely expressed by this famous image by Imogen Cunningham:

I believe that the world is a better place because these photographers taught themselves to see, and then encouraged us to do the same. Dorothea Lange’s well-known work includes images of migrant workers, but I think I like this one best:

Or maybe this one. Ms. Lange gets out, grabs the camera, finds the angle, and creates a memorable self-portrait.

Time for me to re-read the Ansel biography, I think. Good news—the same publisher (Bloomsbury) has reissued the book with some new material and additional insights. I can’t wait.

Please Comment